6.4: 操作条件

- Page ID

- 203547

学习目标

- 定义操作条件

- 解释强化与惩罚的区别

- 区分加固计划

本章的前一节重点介绍了被称为经典条件的联想学习类型。 请记住,在传统条件下,环境中的某些东西会自动触发反射,研究人员训练生物体对不同的刺激做出反应。 现在我们转向第二种类型的联想学习,即操作条件调节。 在操作条件下,生物学会将行为及其后果联系起来(见下表)。 令人愉快的结果使这种行为将来更有可能重演。 例如,巴尔的摩国家水族馆的一只海豚 Spirit 在训练师吹口哨时会在空中翻转。 结果是她得到了一条鱼。

| 经典调理 | 操作员调节 | |

|---|---|---|

| 调理方法 | 无条件刺激(例如食物)与中性刺激(例如铃铛)配对。 中性刺激最终变成了条件刺激,它带来了条件性反应(流涎)。 | 目标行为之后是强化或惩罚,以强化或削弱它,这样学习者将来更有可能表现出想要的行为。 |

| 刺激时机 | 刺激发生在反应之前。 | 刺激(强化或惩罚)发生在反应后不久。 |

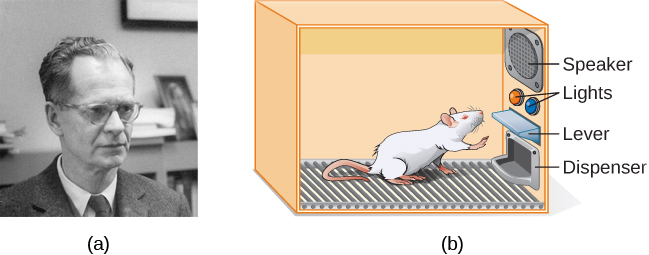

心理学家 B. F. Skinner 认为,传统条件仅限于反身引发的现有行为,它不包括骑自行车等新行为。 他提出了一个关于这种行为是如何产生的理论。 斯金纳认为,行为的动机是我们因行为而受到的后果:增援和惩罚。 他认为学习是后果的结果的观点是基于心理学家爱德华· 桑代克最初提出的效果定律。 根据效果定律,随之而来的是令生物体满意的后果的行为更有可能重演,而随后出现不愉快后果的行为则不太可能重演(Thorndike,1911)。 从本质上讲,如果一个生物体做了能带来预期结果的事情,那么该生物体更有可能再次这样做。 如果一个生物体做了不能带来预期结果的事情,那么该生物体就不太可能再做一次。 效应法则的一个例子是就业。 我们上班的原因之一(通常也是主要原因)是因为我们因此获得报酬。 如果我们停止获得报酬,即使我们热爱我们的工作,我们也可能会停止露面。

斯金纳以桑代克的效应定律为基础,开始对动物(主要是老鼠和鸽子)进行科学实验,以确定生物如何通过操作条件学习(Skinner,1938 年)。 他将这些动物放在操作员调理室里,该室后来被称为 “Skinner box”。 Skinner 盒子里有一个杠杆(用于老鼠)或圆盘(用于鸽子),动物可以通过分配器按下或啄食以获得食物奖励。 扬声器和灯光可能与某些行为相关联。 记录器计算动物的反应次数。

在讨论操作条件时,我们以专门的方式使用了几个日常用语——正面、负面、强化和惩罚。 在操作条件下,正面和负面并不意味着好与坏。 相反,正面意味着你在添加一些东西,而负面意味着你在拿走一些东西。 强化意味着你在增加一种行为,而惩罚意味着你在减少一种行为。 强化可以是正面的也可以是负面的,惩罚也可以是正面的,也可以是负面的。 所有强化剂(正面或负面)都会增加行为反应的可能性。 所有惩罚者(正面或负面)都会降低行为反应的可能性。 现在让我们把这四个术语结合起来:正强化、负强化、积极惩罚和消极惩罚。 (参见下表。)

| 加固 | 惩罚 | |

|---|---|---|

| 阳性 | 添加了一些东西来增加行为发生的可能性。 | 添加了一些东西来降低行为发生的可能性。 |

| 负面的 | 移除某些东西以增加发生行为的可能性。 | 移除某些内容以降低行为发生的可能性。 |

加固

教导人或动物新行为的最有效方法是积极强化。 在正向强化中,添加了理想的刺激来增加行为。

例如,你告诉你五岁的儿子杰罗姆,如果他打扫房间,他会得到一个玩具。 杰罗姆很快就打扫了房间,因为他想要一套新的艺术套装。 让我们暂停片刻。 有些人可能会说:“我为什么要奖励我的孩子做了预期的事情?” 但实际上,我们在生活中不断获得回报。 我们的薪水是奖励,高分和被我们首选学校录取也是如此。 因表现出色和通过驾驶员考试而受到称赞也是一种奖励。 积极强化作为一种学习工具非常有效。 研究发现,在阅读分数低于平均水平的学区提高成绩的最有效方法之一是付钱给孩子读书。 具体而言,达拉斯的二年级学生\(\$2\)每次读一本书并通过关于这本书的简短测验都会获得报酬。 结果是阅读理解能力显著提高(Fryer,2010)。 你觉得这个程序怎么样? 如果斯金纳今天还活着,他可能会认为这是个好主意。 他坚决支持使用操作条件原则来影响学生在学校的行为。 事实上,除了 Skinner Box 之外,他还发明了他所谓的教学机器,旨在奖励学习中的小步骤(Skinner,1961 年),这是计算机辅助学习的早期先驱。 他的教学机器测试了学生在学习各种学校科目时的知识。 如果学生正确回答问题,他们会立即得到积极的强化并可以继续;如果他们回答不正确,他们就不会得到任何强化。 当时的想法是让学生花更多时间学习材料,以增加他们下次获得强化的机会(Skinner,1961 年)。

在负强化中,消除不良刺激以增加行为。 例如,汽车制造商在其安全带系统中使用负加固原理,在你系好安全带之前,安全带会发出 “哔声、哔哔声、哔声”。 当你表现出想要的行为时,烦人的声音就会停止,这增加了你将来屈服的可能性。 负强化也经常用于骑马训练。 骑手施加压力(通过拉动缰绳或挤压双腿),然后在马匹表现出所需的行为(例如转弯或加速)时移除压力。 压力是马匹想要消除的负面刺激。

Punishment

Many people confuse negative reinforcement with punishment in operant conditioning, but they are two very different mechanisms. Remember that reinforcement, even when it is negative, always increases a behavior. In contrast, punishment always decreases a behavior. In positive punishment, you add an undesirable stimulus to decrease a behavior. An example of positive punishment is scolding a student to get the student to stop texting in class. In this case, a stimulus (the reprimand) is added in order to decrease the behavior (texting in class). In negative punishment, you remove an aversive stimulus to decrease behavior. For example, when a child misbehaves, a parent can take away a favorite toy. In this case, a stimulus (the toy) is removed in order to decrease the behavior.

Punishment, especially when it is immediate, is one way to decrease undesirable behavior. For example, imagine your four-year-old son, Brandon, hit his younger brother. You have Brandon write \(100\) times “I will not hit my brother" (positive punishment). Chances are he won’t repeat this behavior. While strategies like this are common today, in the past children were often subject to physical punishment, such as spanking. It’s important to be aware of some of the drawbacks in using physical punishment on children. First, punishment may teach fear. Brandon may become fearful of the street, but he also may become fearful of the person who delivered the punishment—you, his parent. Similarly, children who are punished by teachers may come to fear the teacher and try to avoid school (Gershoff et al., 2010). Consequently, most schools in the United States have banned corporal punishment. Second, punishment may cause children to become more aggressive and prone to antisocial behavior and delinquency (Gershoff, 2002). They see their parents resort to spanking when they become angry and frustrated, so, in turn, they may act out this same behavior when they become angry and frustrated. For example, because you spank Brenda when you are angry with her for her misbehavior, she might start hitting her friends when they won’t share their toys.

While positive punishment can be effective in some cases, Skinner suggested that the use of punishment should be weighed against the possible negative effects. Today’s psychologists and parenting experts favor reinforcement over punishment—they recommend that you catch your child doing something good and reward her for it.

Shaping

In his operant conditioning experiments, Skinner often used an approach called shaping. Instead of rewarding only the target behavior, in shaping, we reward successive approximations of a target behavior. Why is shaping needed? Remember that in order for reinforcement to work, the organism must first display the behavior. Shaping is needed because it is extremely unlikely that an organism will display anything but the simplest of behaviors spontaneously. In shaping, behaviors are broken down into many small, achievable steps. The specific steps used in the process are the following:

- Reinforce any response that resembles the desired behavior.

- Then reinforce the response that more closely resembles the desired behavior. You will no longer reinforce the previously reinforced response.

- Next, begin to reinforce the response that even more closely resembles the desired behavior.

- Continue to reinforce closer and closer approximations of the desired behavior.

- Finally, only reinforce the desired behavior.

Shaping is often used in teaching a complex behavior or chain of behaviors. Skinner used shaping to teach pigeons not only such relatively simple behaviors as pecking a disk in a Skinner box, but also many unusual and entertaining behaviors, such as turning in circles, walking in figure eights, and even playing ping pong; the technique is commonly used by animal trainers today. An important part of shaping is stimulus discrimination. Recall Pavlov’s dogs—he trained them to respond to the tone of a bell, and not to similar tones or sounds. This discrimination is also important in operant conditioning and in shaping behavior.

It’s easy to see how shaping is effective in teaching behaviors to animals, but how does shaping work with humans? Let’s consider parents whose goal is to have their child learn to clean his room. They use shaping to help him master steps toward the goal. Instead of performing the entire task, they set up these steps and reinforce each step. First, he cleans up one toy. Second, he cleans up five toys. Third, he chooses whether to pick up ten toys or put his books and clothes away. Fourth, he cleans up everything except two toys. Finally, he cleans his entire room.

Primary and Secondary Reinforcers

Rewards such as stickers, praise, money, toys, and more can be used to reinforce learning. Let’s go back to Skinner’s rats again. How did the rats learn to press the lever in the Skinner box? They were rewarded with food each time they pressed the lever. For animals, food would be an obvious reinforcer.

What would be a good reinforce for humans? For your daughter Sydney, it was the promise of a toy if she cleaned her room. How about Joaquin, the soccer player? If you gave Joaquin a piece of candy every time he made a goal, you would be using a primary reinforcer. Primary reinforcers are reinforcers that have innate reinforcing qualities. These kinds of reinforcers are not learned. Water, food, sleep, shelter, sex, and touch, among others, are primary reinforcers. Pleasure is also a primary reinforcer. Organisms do not lose their drive for these things. For most people, jumping in a cool lake on a very hot day would be reinforcing and the cool lake would be innately reinforcing—the water would cool the person off (a physical need), as well as provide pleasure.

A secondary reinforcer has no inherent value and only has reinforcing qualities when linked with a primary reinforcer. Praise, linked to affection, is one example of a secondary reinforcer, as when you called out “Great shot!” every time Joaquin made a goal. Another example, money, is only worth something when you can use it to buy other things—either things that satisfy basic needs (food, water, shelter—all primary reinforcers) or other secondary reinforcers. If you were on a remote island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and you had stacks of money, the money would not be useful if you could not spend it. What about the stickers on the behavior chart? They also are secondary reinforcers.

Sometimes, instead of stickers on a sticker chart, a token is used. Tokens, which are also secondary reinforcers, can then be traded in for rewards and prizes. Entire behavior management systems, known as token economies, are built around the use of these kinds of token reinforcers. Token economies have been found to be very effective at modifying behavior in a variety of settings such as schools, prisons, and mental hospitals. For example, a study by Cangi and Daly (2013) found that use of a token economy increased appropriate social behaviors and reduced inappropriate behaviors in a group of autistic school children. Autistic children tend to exhibit disruptive behaviors such as pinching and hitting. When the children in the study exhibited appropriate behavior (not hitting or pinching), they received a “quiet hands” token. When they hit or pinched, they lost a token. The children could then exchange specified amounts of tokens for minutes of playtime.

EVERYDAY CONNECTION: Behavior Modification in Children

Parents and teachers often use behavior modification to change a child’s behavior. Behavior modification uses the principles of operant conditioning to accomplish behavior change so that undesirable behaviors are switched for more socially acceptable ones. Some teachers and parents create a sticker chart, in which several behaviors are listed (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). Sticker charts are a form of token economies, as described in the text. Each time children perform the behavior, they get a sticker, and after a certain number of stickers, they get a prize, or reinforcer. The goal is to increase acceptable behaviors and decrease misbehavior. Remember, it is best to reinforce desired behaviors, rather than to use punishment. In the classroom, the teacher can reinforce a wide range of behaviors, from students raising their hands, to walking quietly in the hall, to turning in their homework. At home, parents might create a behavior chart that rewards children for things such as putting away toys, brushing their teeth, and helping with dinner. In order for behavior modification to be effective, the reinforcement needs to be connected with the behavior; the reinforcement must matter to the child and be done consistently.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Sticker charts are a form of positive reinforcement and a tool for behavior modification. Once this little girl earns a certain number of stickers for demonstrating a desired behavior, she will be rewarded with a trip to the ice cream parlor. (credit: Abigail Batchelder)

Time-out is another popular technique used in behavior modification with children. It operates on the principle of negative punishment. When a child demonstrates an undesirable behavior, she is removed from the desirable activity at hand. For example, say that Sophia and her brother Mario are playing with building blocks. Sophia throws some blocks at her brother, so you give her a warning that she will go to time-out if she does it again. A few minutes later, she throws more blocks at Mario. You remove Sophia from the room for a few minutes. When she comes back, she doesn’t throw blocks.

There are several important points that you should know if you plan to implement time-out as a behavior modification technique. First, make sure the child is being removed from a desirable activity and placed in a less desirable location. If the activity is something undesirable for the child, this technique will backfire because it is more enjoyable for the child to be removed from the activity. Second, the length of the time-out is important. The general rule of thumb is one minute for each year of the child’s age. Sophia is five; therefore, she sits in a time-out for five minutes. Setting a timer helps children know how long they have to sit in time-out. Finally, as a caregiver, keep several guidelines in mind over the course of a time-out: remain calm when directing your child to time-out; ignore your child during time-out (because caregiver attention may reinforce misbehavior); and give the child a hug or a kind word when time-out is over.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Time-out is a popular form of negative punishment used by caregivers. When a child misbehaves, he or she is removed from a desirable activity in an effort to decrease the unwanted behavior. For example, (a) a child might be playing on the playground with friends and push another child; (b) the child who misbehaved would then be removed from the activity for a short period of time. (credit a: modification of work by Simone Ramella; credit b: modification of work by “JefferyTurner”/Flickr)

Reinforcement Schedules

Remember, the best way to teach a person or animal a behavior is to use positive reinforcement. For example, Skinner used positive reinforcement to teach rats to press a lever in a Skinner box. At first, the rat might randomly hit the lever while exploring the box, and out would come a pellet of food. After eating the pellet, what do you think the hungry rat did next? It hit the lever again, and received another pellet of food. Each time the rat hit the lever, a pellet of food came out. When an organism receives a reinforcer each time it displays a behavior, it is called continuous reinforcement. This reinforcement schedule is the quickest way to teach someone a behavior, and it is especially effective in training a new behavior. Let’s look back at the dog that was learning to sit earlier in the chapter. Now, each time he sits, you give him a treat. Timing is important here: you will be most successful if you present the reinforcer immediately after he sits, so that he can make an association between the target behavior (sitting) and the consequence (getting a treat).

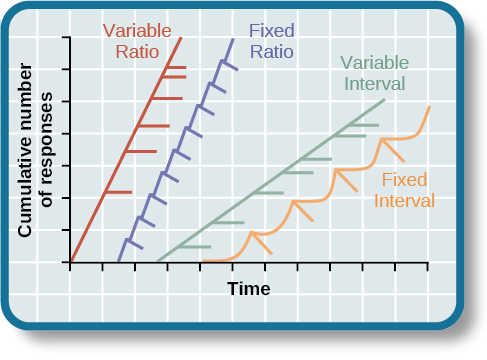

Once a behavior is trained, researchers and trainers often turn to another type of reinforcement schedule—partial reinforcement. In partial reinforcement, also referred to as intermittent reinforcement, the person or animal does not get reinforced every time they perform the desired behavior. There are several different types of partial reinforcement schedules (See table below). These schedules are described as either fixed or variable, and as either interval or ratio. Fixed refers to the number of responses between reinforcements, or the amount of time between reinforcements, which is set and unchanging. Variable refers to the number of responses or amount of time between reinforcements, which varies or changes. Interval means the schedule is based on the time between reinforcements, and ratio means the schedule is based on the number of responses between reinforcements.

| Reinforcement Schedule | Description | Result | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed interval | Reinforcement is delivered at predictable time intervals (e.g., after 5, 10, 15, and 20 minutes). | Moderate response rate with significant pauses after reinforcement | Hospital patient uses patient-controlled, doctor-timed pain relief |

| Variable interval | Reinforcement is delivered at unpredictable time intervals (e.g., after 5, 7, 10, and 20 minutes). | Moderate yet steady response rate | Checking Facebook |

| Fixed ratio | Reinforcement is delivered after a predictable number of responses (e.g., after 2, 4, 6, and 8 responses). | High response rate with pauses after reinforcement | Piecework—factory worker getting paid for every x number of items manufactured |

| Variable ratio | Reinforcement is delivered after an unpredictable number of responses (e.g., after 1, 4, 5, and 9 responses). | High and steady response rate | Gambling |

Now let’s combine these four terms. A fixed interval reinforcement schedule is when behavior is rewarded after a set amount of time. For example, June undergoes major surgery in a hospital. During recovery, she is expected to experience pain and will require prescription medications for pain relief. June is given an IV drip with a patient-controlled painkiller. Her doctor sets a limit: one dose per hour. June pushes a button when pain becomes difficult, and she receives a dose of medication. Since the reward (pain relief) only occurs on a fixed interval, there is no point in exhibiting the behavior when it will not be rewarded.

With a variable interval reinforcement schedule, the person or animal gets the reinforcement based on varying amounts of time, which are unpredictable. Say that Manuel is the manager at a fast-food restaurant. Every once in a while someone from the quality control division comes to Manuel’s restaurant. If the restaurant is clean and the service is fast, everyone on that shift earns a \(\$20\) bonus. Manuel never knows when the quality control person will show up, so he always tries to keep the restaurant clean and ensures that his employees provide prompt and courteous service. His productivity regarding prompt service and keeping a clean restaurant are steady because he wants his crew to earn the bonus.

With a fixed ratio reinforcement schedule, there are a set number of responses that must occur before the behavior is rewarded. Carla sells glasses at an eyeglass store, and she earns a commission every time she sells a pair of glasses. She always tries to sell people more pairs of glasses, including prescription sunglasses or a backup pair, so she can increase her commission. She does not care if the person really needs the prescription sunglasses, Carla just wants her bonus. The quality of what Carla sells does not matter because her commission is not based on quality; it’s only based on the number of pairs sold. This distinction in the quality of performance can help determine which reinforcement method is most appropriate for a particular situation. Fixed ratios are better suited to optimize the quantity of output, whereas a fixed interval, in which the reward is not quantity based, can lead to a higher quality of output.

In a variable ratio reinforcement schedule, the number of responses needed for a reward varies. This is the most powerful partial reinforcement schedule. An example of the variable ratio reinforcement schedule is gambling. Imagine that Sarah—generally a smart, thrifty woman—visits Las Vegas for the first time. She is not a gambler, but out of curiosity she puts a quarter into the slot machine, and then another, and another. Nothing happens. Two dollars in quarters later, her curiosity is fading, and she is just about to quit. But then, the machine lights up, bells go off, and Sarah gets \(50\) quarters back. That’s more like it! Sarah gets back to inserting quarters with renewed interest, and a few minutes later she has used up all her gains and is \(\$10\) in the hole. Now might be a sensible time to quit. And yet, she keeps putting money into the slot machine because she never knows when the next reinforcement is coming. She keeps thinking that with the next quarter she could win \(\$50\), or \(\$100\), or even more. Because the reinforcement schedule in most types of gambling has a variable ratio schedule, people keep trying and hoping that the next time they will win big. This is one of the reasons that gambling is so addictive—and so resistant to extinction.

In operant conditioning, extinction of a reinforced behavior occurs at some point after reinforcement stops, and the speed at which this happens depends on the reinforcement schedule. In a variable ratio schedule, the point of extinction comes very slowly, as described above. But in the other reinforcement schedules, extinction may come quickly. For example, if June presses the button for the pain relief medication before the allotted time her doctor has approved, no medication is administered. She is on a fixed interval reinforcement schedule (dosed hourly), so extinction occurs quickly when reinforcement doesn’t come at the expected time. Among the reinforcement schedules, variable ratio is the most productive and the most resistant to extinction. Fixed interval is the least productive and the easiest to extinguish. See figure below.

CONNECT THE CONCEPTS: Gambling and the Brain

Skinner (1953) stated, “If the gambling establishment cannot persuade a patron to turn over money with no return, it may achieve the same effect by returning part of the patron's money on a variable-ratio schedule” (p. 397).

Skinner uses gambling as an example of the power and effectiveness of conditioning behavior based on a variable ratio reinforcement schedule. In fact, Skinner was so confident in his knowledge of gambling addiction that he even claimed he could turn a pigeon into a pathological gambler (“Skinner’s Utopia,” 1971). Beyond the power of variable ratio reinforcement, gambling seems to work on the brain in the same way as some addictive drugs. The Illinois Institute for Addiction Recovery (n.d.) reports evidence suggesting that pathological gambling is an addiction similar to a chemical addiction (See figure below). Specifically, gambling may activate the reward centers of the brain, much like cocaine does. Research has shown that some pathological gamblers have lower levels of the neurotransmitter (brain chemical) known as norepinephrine than do normal gamblers (Roy, et al., 1988). According to a study conducted by Alec Roy and colleagues, norepinephrine is secreted when a person feels stress, arousal, or thrill; pathological gamblers use gambling to increase their levels of this neurotransmitter. Another researcher, neuroscientist Hans Breiter, has done extensive research on gambling and its effects on the brain. Breiter (as cited in Franzen, 2001) reports that “Monetary reward in a gambling-like experiment produces brain activation very similar to that observed in a cocaine addict receiving an infusion of cocaine” (para. 1). Deficiencies in serotonin (another neurotransmitter) might also contribute to compulsive behavior, including a gambling addiction.

It may be that pathological gamblers’ brains are different than those of other people, and perhaps this difference may somehow have led to their gambling addiction, as these studies seem to suggest. However, it is very difficult to ascertain the cause because it is impossible to conduct a true experiment (it would be unethical to try to turn randomly assigned participants into problem gamblers). Therefore, it may be that causation actually moves in the opposite direction—perhaps the act of gambling somehow changes neurotransmitter levels in some gamblers’ brains. It also is possible that some overlooked factor, or confounding variable, played a role in both the gambling addiction and the differences in brain chemistry.

Cognition and Latent Learning

Although strict behaviorists such as Skinner and Watson refused to believe that cognition (such as thoughts and expectations) plays a role in learning, another behaviorist, Edward C. Tolman, had a different opinion. Tolman’s experiments with rats demonstrated that organisms can learn even if they do not receive immediate reinforcement (Tolman & Honzik, 1930; Tolman, Ritchie, & Kalish, 1946). This finding was in conflict with the prevailing idea at the time that reinforcement must be immediate in order for learning to occur, thus suggesting a cognitive aspect to learning.

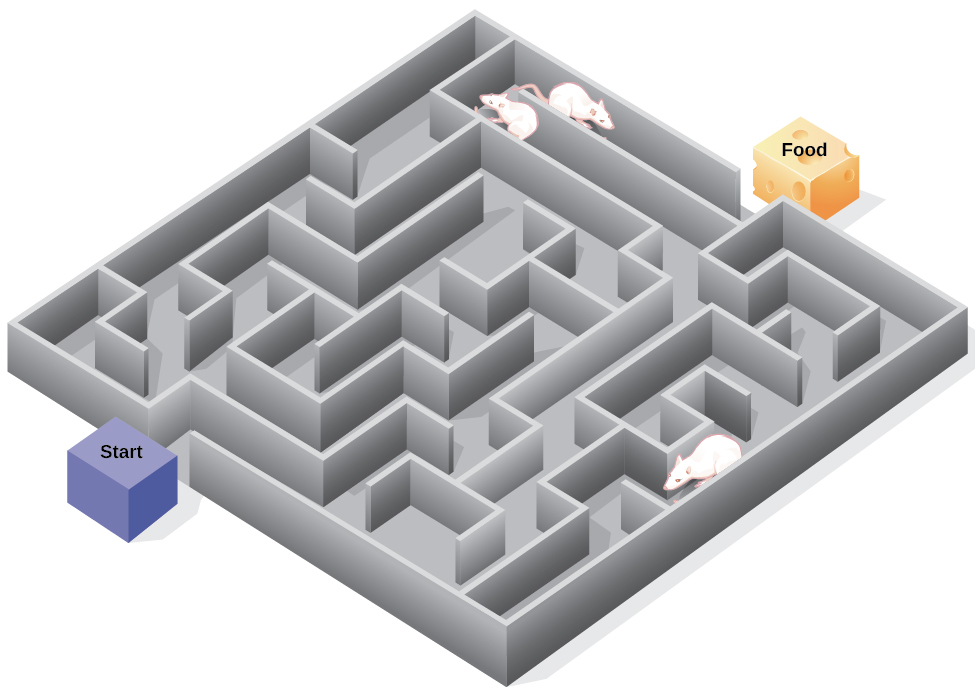

In the experiments, Tolman placed hungry rats in a maze with no reward for finding their way through it. He also studied a comparison group that was rewarded with food at the end of the maze. As the unreinforced rats explored the maze, they developed a cognitive map: a mental picture of the layout of the maze (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). After \(10\) sessions in the maze without reinforcement, food was placed in a goal box at the end of the maze. As soon as the rats became aware of the food, they were able to find their way through the maze quickly, just as quickly as the comparison group, which had been rewarded with food all along. This is known as latent learning: learning that occurs but is not observable in behavior until there is a reason to demonstrate it.

Latent learning also occurs in humans. Children may learn by watching the actions of their parents but only demonstrate it at a later date, when the learned material is needed. For example, suppose that Ravi’s dad drives him to school every day. In this way, Ravi learns the route from his house to his school, but he’s never driven there himself, so he has not had a chance to demonstrate that he’s learned the way. One morning Ravi’s dad has to leave early for a meeting, so he can’t drive Ravi to school. Instead, Ravi follows the same route on his bike that his dad would have taken in the car. This demonstrates latent learning. Ravi had learned the route to school, but had no need to demonstrate this knowledge earlier.

EVERYDAY CONNECTION: This Place Is Like a Maze

Have you ever gotten lost in a building and couldn’t find your way back out? While that can be frustrating, you’re not alone. At one time or another we’ve all gotten lost in places like a museum, hospital, or university library. Whenever we go someplace new, we build a mental representation—or cognitive map—of the location, as Tolman’s rats built a cognitive map of their maze. However, some buildings are confusing because they include many areas that look alike or have short lines of sight. Because of this, it’s often difficult to predict what’s around a corner or decide whether to turn left or right to get out of a building. Psychologist Laura Carlson (2010) suggests that what we place in our cognitive map can impact our success in navigating through the environment. She suggests that paying attention to specific features upon entering a building, such as a picture on the wall, a fountain, a statue, or an escalator, adds information to our cognitive map that can be used later to help find our way out of the building.

Summary

Operant conditioning is based on the work of B. F. Skinner. Operant conditioning is a form of learning in which the motivation for a behavior happens after the behavior is demonstrated. An animal or a human receives a consequence after performing a specific behavior. The consequence is either a reinforcer or a punisher. All reinforcement (positive or negative) increases the likelihood of a behavioral response. All punishment (positive or negative) decreases the likelihood of a behavioral response. Several types of reinforcement schedules are used to reward behavior depending on either a set or variable period of time.

Glossary

- cognitive map

- mental picture of the layout of the environment

- continuous reinforcement

- rewarding a behavior every time it occurs

- fixed interval reinforcement schedule

- behavior is rewarded after a set amount of time

- fixed ratio reinforcement schedule

- set number of responses must occur before a behavior is rewarded

- latent learning

- learning that occurs, but it may not be evident until there is a reason to demonstrate it

- law of effect

- behavior that is followed by consequences satisfying to the organism will be repeated and behaviors that are followed by unpleasant consequences will be discouraged

- negative punishment

- taking away a pleasant stimulus to decrease or stop a behavior

- negative reinforcement

- taking away an undesirable stimulus to increase a behavior

- operant conditioning

- form of learning in which the stimulus/experience happens after the behavior is demonstrated

- partial reinforcement

- rewarding behavior only some of the time

- positive punishment

- adding an undesirable stimulus to stop or decrease a behavior

- positive reinforcement

- adding a desirable stimulus to increase a behavior

- primary reinforcer

- has innate reinforcing qualities (e.g., food, water, shelter, sex)

- punishment

- implementation of a consequence in order to decrease a behavior

- reinforcement

- implementation of a consequence in order to increase a behavior

- secondary reinforcer

- has no inherent value unto itself and only has reinforcing qualities when linked with something else (e.g., money, gold stars, poker chips)

- shaping

- rewarding successive approximations toward a target behavior

- variable interval reinforcement schedule

- behavior is rewarded after unpredictable amounts of time have passed

- variable ratio reinforcement schedule

- number of responses differ before a behavior is rewarded