4.E : Stoechiométrie des réactions chimiques (exercices)

- Page ID

- 194081

4.1 : Écrire et équilibrer des équations chimiques

Q4.1.1

Qu'est-ce que cela signifie de dire qu'une équation est équilibrée ? Pourquoi est-il important qu'une équation soit équilibrée ?

S4.1.1

Une équation est équilibrée lorsque le même nombre de chaque élément est représenté du côté du réactif et du côté du produit. Les équations doivent être équilibrées pour refléter avec précision la loi de conservation de la matière.

Q4.1.2

Examinez les équations moléculaires, ioniques complètes et ioniques nettes.

- Quelle est la différence entre ces types d'équations ?

- Dans quelles circonstances les équations ioniques complètes et nettes d'une réaction seraient-elles identiques ?

Q4.1.3

Équilibrez les équations suivantes :

- \(\ce{PCl5}(s)+\ce{H2O}(l)\rightarrow \ce{POCl3}(l)+\ce{HCl}(aq)\)

- \(\ce{Cu}(s)+\ce{HNO3}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Cu(NO3)2}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)+\ce{NO}(g)\)

- \(\ce{H2}(g)+\ce{I2}(s)\rightarrow \ce{HI}(s)\)

- \(\ce{Fe}(s)+\ce{O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{Fe2O3}(s)\)

- \(\ce{Na}(s)+\ce{H2O}(l)\rightarrow \ce{NaOH}(aq)+\ce{H2}(g)\)

- \(\ce{(NH4)2Cr2O7}(s)\rightarrow \ce{Cr2O3}(s)+\ce{N2}(g)+\ce{H2O}(g)\)

- \(\ce{P4}(s)+\ce{Cl2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{PCl3}(l)\)

- \(\ce{PtCl4}(s)\rightarrow \ce{Pt}(s)+\ce{Cl2}(g)\)

4.1.3

- \(\ce{PCl5}(s)+\ce{H2O}(l)\rightarrow \ce{POCl3}(l)+\ce{2HCl}(aq)\);

- \(\ce{3Cu}(s)+\ce{8HNO3}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{3Cu(NO3)2}(aq)+\ce{4H2O}(l)+\ce{2NO}(g)\);

- \(\ce{H2}(g)+\ce{I2}(s)\rightarrow \ce{2HI}(s)\);

- \(\ce{4Fe}(s)+\ce{3O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{2Fe2O3}(s)\);

- \(\ce{2Na}(s)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\rightarrow \ce{2NaOH}(aq)+\ce{H2}(g)\);

- \(\ce{(NH4)2Cr52O7}(s)\rightarrow \ce{Cr2O3}(s)+\ce{N2}(g)+\ce{4H2O}(g)\);

- \(\ce{P4}(s)+\ce{6Cl2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{4PCl3}(l)\);

- \(\ce{PtCl4}(s)\rightarrow \ce{Pt}(s)+\ce{2Cl2}(g)\)

Q4.1.4

Équilibrez les équations suivantes :

- \(\ce{Ag}(s)+\ce{H2S}(g)+\ce{O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{Ag2S}(s)+\ce{H2O}(l)\)

- \(\ce{P4}(s)+\ce{O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{P4O10}(s)\)

- \(\ce{Pb}(s)+\ce{H2O}(l)+\ce{O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{Pb(OH)2}(s)\)

- \(\ce{Fe}(s)+\ce{H2O}(l)\rightarrow \ce{Fe3O4}(s)+\ce{H2}(g)\)

- \(\ce{Sc2O3}(s)+\ce{SO3}(l)\rightarrow \ce{Sc2(SO4)3}(s)\)

- \(\ce{Ca3(PO4)2}(aq)+\ce{H3PO4}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Ca(H2PO4)2}(aq)\)

- \(\ce{Al}(s)+\ce{H2SO4}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Al2(SO4)3}(s)+\ce{H2}(g)\)

- \(\ce{TiCl4}(s)+\ce{H2O}(g)\rightarrow \ce{TiO2}(s)+\ce{HCl}(g)\)

S4.1.4

- \(\ce{4Ag}(s)+\ce{2H2S}(g)+\ce{O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{2Ag2S}(s)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\)

- \(\ce{P4}(s)+\ce{5O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{P4O10}(s)\)

- \(\ce{2Pb}(s)+\ce{2H2O}(l)+\ce{O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{2Pb(OH)2}(s)\)

- \(\ce{3Fe}(s)+\ce{4H2O}(l)\rightarrow \ce{Fe3O4}(s)+\ce{4H2}(g)\)

- \(\ce{Sc2O3}(s)+\ce{3SO3}(l)\rightarrow \ce{Sc2(SO4)3}(s)\)

- \(\ce{Ca3(PO4)2}(aq)+\ce{4H3PO4}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{3Ca(H2PO4)2}(aq)\)

- \(\ce{2Al}(s)+\ce{3H2SO4}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Al2(SO4)3}(s)+\ce{3H2}(g)\)

- \(\ce{TiCl4}(s)+\ce{2H2O}(g)\rightarrow \ce{TiO2}(s)+\ce{4HCl}(g)\)

Q4.1.5

Rédigez une équation moléculaire équilibrée décrivant chacune des réactions chimiques suivantes.

- Le carbonate de calcium solide est chauffé et se décompose en oxyde de calcium solide et en dioxyde de carbone gazeux.

- Le butane gazeux, C 4 H 10, réagit avec l'oxygène diatomique pour produire du dioxyde de carbone gazeux et de la vapeur d'eau.

- Les solutions aqueuses de chlorure de magnésium et d'hydroxyde de sodium réagissent pour produire de l'hydroxyde de magnésium solide et du chlorure de sodium

- La vapeur d'eau réagit avec le sodium métallique pour produire de l'hydroxyde de sodium solide et de l'hydrogène.

4.1.5

- \(\ce{CaCO3}(s)\rightarrow \ce{CaO}(s)+\ce{CO2}(g)\);

- \(\ce{2C4H10}(g)+\ce{13O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{8CO2}(g)+\ce{10H2O}(g)\);

- \(\ce{MgCl2}(aq)+\ce{2NaOH}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Mg(OH)2}(s)+\ce{2NaCl}(aq)\);

- \(\ce{2H2O}(g)+\ce{2Na}(s)\rightarrow \ce{2NaOH}(s)+\ce{H2}(g)\)

Q4.1.6

Rédigez une équation équilibrée décrivant chacune des réactions chimiques suivantes.

- Le chlorate de potassium solide, KClO 3, se décompose pour former du chlorure de potassium solide et de l'oxygène diatomique.

- L'aluminium solide réagit avec l'iode diatomique solide pour former de l'Al 2 I 6 solide.

- Lorsque du chlorure de sodium solide est ajouté à de l'acide sulfurique aqueux, du chlorure d'hydrogène gazeux et du sulfate de sodium aqueux sont produits.

- Les solutions aqueuses d'acide phosphorique et d'hydroxyde de potassium réagissent pour produire du phosphate monopotassique aqueux et de l'eau liquide.

Q4.1.7

Les feux d'artifice colorés impliquent souvent la décomposition du nitrate de baryum et du chlorate de potassium et la réaction des métaux magnésium, aluminium et fer avec l'oxygène.

- Écrivez les formules du nitrate de baryum et du chlorate de potassium.

- La décomposition du chlorate de potassium solide entraîne la formation de chlorure de potassium solide et d'oxygène diatomique. Ecrivez une équation pour la réaction.

- La décomposition du nitrate de baryum solide entraîne la formation d'oxyde de baryum solide, d'azote diatomique et d'oxygène diatomique. Ecrivez une équation pour la réaction.

- Écrivez des équations distinctes pour les réactions des métaux solides que sont le magnésium, l'aluminium et le fer avec l'oxygène diatomique afin d'obtenir les oxydes métalliques correspondants. (Supposons que l'oxyde de fer contienne des ions Fe 3+.)

Q4.1.7

- Ba (NO 32), KClO 3 ;

- \(\ce{2KClO3}(s)\rightarrow \ce{2KCl}(s)+\ce{3O2}(g)\);

- \(\ce{2Ba(NO3)2}(s)\rightarrow \ce{2BaO}(s)+\ce{2N2}(g)+\ce{5O2}(g)\);

- \(\ce{2Mg}(s)+\ce{O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{2MgO}(s)\);\(\ce{4Al}(s)+\ce{3O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{2Al2O3}(g)\) ;\(\ce{4Fe}(s)+\ce{3O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{2Fe2O3}(s)\)

Q4.1.8

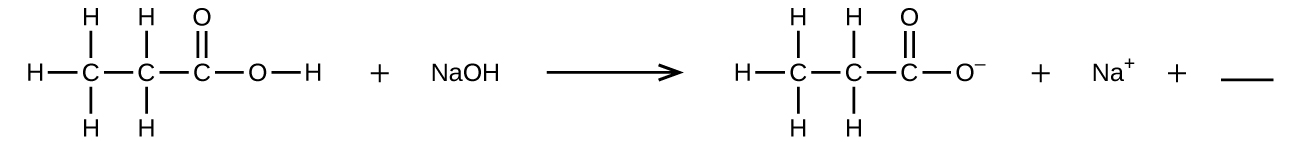

Remplissez le blanc avec une formule chimique unique pour un composé covalent qui équilibrera l'équation :

Q4.1.9

Le fluorure d'hydrogène aqueux (acide fluorhydrique) est utilisé pour graver le verre et pour analyser la teneur en silicium des minéraux. Le fluorure d'hydrogène réagira également avec le sable (dioxyde de silicium).

- Écrivez une équation pour la réaction du dioxyde de silicium solide avec l'acide fluorhydrique pour obtenir du tétrafluorure de silicium gazeux et de l'eau liquide.

- La fluorite minérale (fluorure de calcium) est largement présente dans l'Illinois. Le fluorure de calcium solide peut également être préparé par réaction de solutions aqueuses de chlorure de calcium et de fluorure de sodium, ce qui donne du chlorure de sodium aqueux comme autre produit. Écrivez des équations ioniques complètes et nettes pour cette réaction.

4.1.9

- \(\ce{4HF}(aq)+\ce{SiO2}(s)\rightarrow \ce{SiF4}(g)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\);

- équation ionique complète :\(\ce{2Na+}(aq)+\ce{2F-}(aq)+\ce{Ca^2+}(aq)+\ce{2Cl-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{CaF2}(s)+\ce{2Na+}(aq)+\ce{2Cl-}(aq)\), équation ionique nette :\(\ce{2F-}(aq)+\ce{Ca^2+}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{CaF2}(s)\)

Q4.1.10

Un nouveau procédé d'obtention de magnésium à partir d'eau de mer implique plusieurs réactions. Écrivez une équation chimique équilibrée pour chaque étape du procédé.

- La première étape consiste à décomposer le carbonate de calcium solide des coquillages pour former de l'oxyde de calcium solide et du dioxyde de carbone gazeux.

- La deuxième étape consiste à former de l'hydroxyde de calcium solide comme seul produit de la réaction de l'oxyde de calcium solide avec de l'eau liquide.

- De l'hydroxyde de calcium solide est ensuite ajouté à l'eau de mer, réagissant avec du chlorure de magnésium dissous pour produire de l'hydroxyde de magnésium solide et du chlorure de calcium aqueux.

- L'hydroxyde de magnésium solide est ajouté à une solution d'acide chlorhydrique, produisant du chlorure de magnésium dissous et de l'eau liquide.

- Enfin, le chlorure de magnésium est fondu et électrolysé pour produire du magnésium métallique liquide et du chlore diatomique gazeux.

Q4.1.11

À partir des équations moléculaires équilibrées, écrivez les équations ioniques complètes et ioniques nettes pour ce qui suit :

- \(\ce{K2C2O4}(aq)+\ce{Ba(OH)2}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{2KOH}(aq)+\ce{BaC2O2}(s)\)

- \(\ce{Pb(NO3)2}(aq)+\ce{H2SO4}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{PbSO4}(s)+\ce{2HNO3}(aq)\)

- \(\ce{CaCO3}(s)+\ce{H2SO4}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{CaSO4}(s)+\ce{CO2}(g)+\ce{H2O}(l)\)

4.1.11

- \[\ce{2K+}(aq)+\ce{C2O4^2-}(aq)+\ce{Ba^2+}(aq)+\ce{2OH-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{2K+}(aq)+\ce{2OH-}(aq)+\ce{BaC2O4}(s)\hspace{20px}\ce{(complete)}\]\[\ce{Ba^2+}(aq)+\ce{C2O4^2-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{BaC2O4}(s)\hspace{20px}\ce{(net)}\]

- \[\ce{Pb^2+}(aq)+\ce{2NO3-}(aq)+\ce{2H+}(aq)+\ce{SO4^2-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{PbSO4}(s)+\ce{2H+}(aq)+\ce{2NO3-}(aq)\hspace{20px}\ce{(complete)}\]\[\ce{Pb^2+}(aq)+\ce{SO4^2-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{PbSO4}(s)\hspace{20px}\ce{(net)}\]

- \[\ce{CaCO3}(s)+\ce{2H+}(aq)+\ce{SO4^2-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{CaSO4}(s)+\ce{CO2}(g)+\ce{H2O}(l)\hspace{20px}\ce{(complete)}\]\[\ce{CaCO3}(s)+\ce{2H+}(aq)+\ce{SO4^2-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{CaSO4}(s)+\ce{CO2}(g)+\ce{H2O}(l)\hspace{20px}\ce{(net)}\]

4.2 : Classification des réactions chimiques

Q4.2.1

Utilisez les équations suivantes pour répondre aux cinq questions suivantes :

- \(\ce{H2O}(s)\rightarrow \ce{H2O}(l)\)

- \(\ce{Na+}(aq)+\ce{Cl-}(aq)\ce{Ag+}(aq)+\ce{NO3-}(aq) \rightarrow \ce{AgCl}(s)+\ce{Na+}(aq)+\ce{NO3-}(aq)\)

- \(\ce{CH3OH}(g)+\ce{O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{CO2}(g)+\ce{H2O}(g)\)

- \(\ce{2H2O}(l)\rightarrow \ce{2H2}(g)+\ce{O2}(g)\)

- \(\ce{H+}(aq)+\ce{OH-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{H2O}(l)\)

- Quelle équation décrit un changement physique ?

- Quelle équation identifie les réactifs et les produits d'une réaction de combustion ?

- Quelle équation n'est pas équilibrée ?

- Qu'est-ce qu'une équation ionique nette ?

S4.2.1

un.) je.\(H_2O (solid) → H_2O(liquid)\)

b.) iii.

c.) iii. \(\ce{2CH3OH}(g)+\ce{3O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{2CO2}(g)+\ce{4H2O}(g)\)

d). c.

Q4.2.2

Indiquez le type ou les types de réaction que chacun des éléments suivants représente :

- \(\ce{Ca}(s)+\ce{Br2}(l)\rightarrow \ce{CaBr2}(s)\)

- \(\ce{Ca(OH)2}(aq)+\ce{2HBr}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{CaBr2}(aq)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\)

- \(\ce{C6H12}(l)+\ce{9O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{6CO2}(g)+\ce{6H2O}(g)\)

4.2.2

oxydoréduction (addition) ; acide-base (neutralisation) ; oxydoréduction (combustion)

<

Q4.2.3

Indiquez le type ou les types de réaction que chacun des éléments suivants représente :

- \(\ce{H2O}(g)+\ce{C}(s)\rightarrow \ce{CO}(g)+\ce{H2}(g)\)

- \(\ce{2KClO3}(s)\rightarrow \ce{2KCl}(s)+\ce{3O2}(g)\)

- \(\ce{Al(OH)3}(aq)+\ce{3HCl}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{AlBr3}(aq)+\ce{3H2O}(l)\)

- \(\ce{Pb(NO3)2}(aq)+\ce{H2SO4}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{PbSO4}(s)+\ce{2HNO3}(aq)\)

Q4.2.4

L'argent peut être séparé de l'or parce que l'argent se dissout dans l'acide nitrique alors que l'or ne le fait pas. La dissolution de l'argent dans l'acide nitrique est-elle une réaction acide-base ou une réaction d'oxydoréduction ? Expliquez votre réponse.

S4.2.4

Il s'agit d'une réaction d'oxydoréduction car l'état d'oxydation de l'argent change au cours de la réaction.

Q4.2.5

Déterminer les états d'oxydation des éléments dans les composés suivants :

- NAI

- GdCl 3

- Ligne 3

- H 2 Voir

- Mg 2 Si

- RbO 2, superoxyde de rubidium

- HF

Q4.2.6

Déterminez les états d'oxydation des éléments contenus dans les composés répertoriés. Aucun des composés contenant de l'oxygène n'est un peroxyde ou un superoxyde.

- H 3 PO 4

- Al (OH) 3

- SEO 2

- NUMÉRO 2

- En 2 S 3

- P 4 DE 6

4.2.6

H +1, P +5, O −2 ; Al +3, H +1, O −2 ; Se +4, O −2 ; K +1, N +3, O −2 ; Dans +3, S −2 ; P +3, O −2

Q4.2.7

Déterminez les états d'oxydation des éléments contenus dans les composés répertoriés. Aucun des composés contenant de l'oxygène n'est un peroxyde ou un superoxyde.

- H 2 SO 4

- Ca (OH) 2

- Broh

- CLnO 2

- TiCl 4

- Ah !

4.2.7

- H 1+, O 2 -, S 6+

- H 1+, O 2 -, Ca +2

- H 1+, O 2 -, Br 1+

- O 2 -, Cl 1-, N 5+

- Cl 1-, Ti 4+

- H 1+, Na 1-

Q4.2.8

Classer les éléments suivants en tant que réactions acido-basiques ou réactions d'oxydoréduction :

- \(\ce{Na2S}(aq)+\ce{2HCl}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{2NaCl}(aq)+\ce{H2S}(g)\)

- \(\ce{2Na}(s)+\ce{2HCl}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{2NaCl}(aq)+\ce{H2}(g)\)

- \(\ce{Mg}(s)+\ce{Cl2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{MgCl2}(s)\)

- \(\ce{MgO}(s)+\ce{2HCl}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{MgCl2}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)\)

- \(\ce{K3P}(s)+\ce{2O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{K3PO4}(s)\)

- \(\ce{3KOH}(aq)+\ce{H3PO4}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{K3PO4}(aq)+\ce{3H2O}(l)\)

4.2.9

acide-base ; oxydation-réduction : Na est oxydé, H + est réduit ; oxydation-réduction : Mg est oxydé, Cl 2 est réduit ; acide-base ; oxydation-réduction : P 3− est oxydé, O 2 est réduit ; acide-base

Q4.2.10

Identifiez les atomes oxydés et réduits, le changement d'état d'oxydation de chacun et les agents oxydants et réducteurs dans chacune des équations suivantes :

- \(\ce{Mg}(s)+\ce{NiCl2}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{MgCl2}(aq)+\ce{Ni}(s)\)

- \(\ce{PCl3}(l)+\ce{Cl2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{PCl5}(s)\)

- \(\ce{C2H4}(g)+\ce{3O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{2CO2}(g)+\ce{2H2O}(g)\)

- \(\ce{Zn}(s)+\ce{H2SO4}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{ZnSO4}(aq)+\ce{H2}(g)\)

- \(\ce{2K2S2O3}(s)+\ce{I2}(s)\rightarrow \ce{K2S4O6}(s)+\ce{2KI}(s)\)

- \(\ce{3Cu}(s)+\ce{8HNO3}(aq)\rightarrow\ce{3Cu(NO3)2}(aq)+\ce{2NO}(g)+\ce{4H2O}(l)\)

Q4.2.11

Complétez et équilibrez les équations acide-base suivantes :

- Le gaz HCl réagit avec le Ca (OH) 2 (s) solide.

- Une solution de Sr (OH) 2 est ajoutée à une solution de HNO 3.

4.2.11

- \(\ce{2HCl}(g)+\ce{Ca(OH)2}(s)\rightarrow \ce{CaCl2}(s)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\);

- \(\ce{Sr(OH)2}(aq)+\ce{2HNO3}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Sr(NO3)2}(aq)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\)

Q4.2.12

Complétez et équilibrez les équations acide-base suivantes :

- Une solution de HClO 4 est ajoutée à une solution de LiOH.

- Le H 2 SO 4 aqueux réagit avec le NaOH.

- Le Ba (OH) 2 réagit avec le gaz HF.

Q4.2.13

Terminez et équilibrez les réactions d'oxydoréduction suivantes, qui permettent d'obtenir l'état d'oxydation le plus élevé possible pour les atomes oxydés.

- \(\ce{Al}(s)+\ce{F2}(g)\rightarrow\)

- \(\ce{Al}(s)+\ce{CuBr2}(aq)\rightarrow\)(déplacement unique)

- \(\ce{P4}(s)+\ce{O2}(g)\rightarrow \)

- \(\ce{Ca}(s)+\ce{H2O}(l)\rightarrow \)(les produits sont une base solide et un gaz diatomique)

ARTICLE 4.2.13

- \(\ce{2Al}(s)+\ce{3F2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{2AlF3}(s)\);

- \(\ce{2Al}(s)+\ce{3CuBr2}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{3Cu}(s)+\ce{2AlBr3}(aq)\);

- \(\ce{P4}(s)+\ce{5O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{P4O10}(s)\);\(\ce{Ca}(s)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\rightarrow \ce{Ca(OH)2}(aq)+\ce{H2}(g)\)

Q4.2.14

Terminez et équilibrez les réactions d'oxydoréduction suivantes, qui permettent d'obtenir l'état d'oxydation le plus élevé possible pour les atomes oxydés.

- \(\ce{K}(s)+\ce{H2O}(l)\rightarrow \)

- \(\ce{Ba}(s)+\ce{HBr}(aq)\rightarrow \)

- \(\ce{Sn}(s)+\ce{I2}(s)\rightarrow \)

Q4.2.15

Compléter et équilibrer les équations pour les réactions de neutralisation acide-base suivantes. Si de l'eau est utilisée comme solvant, inscrivez les réactifs et les produits sous forme d'ions aqueux. Dans certains cas, il peut y avoir plus d'une bonne réponse, selon les quantités de réactifs utilisées.

- \(\ce{Mg(OH)2}(s)+\ce{HClO4}(aq)\rightarrow \)

- \(\ce{SO3}(g)+\ce{H2O}(l)\rightarrow \)(supposons un excès d'eau et que le produit se dissout)

- \(\ce{SrO}(s)+\ce{H2SO4}(l)\rightarrow \)

ARTICLE 4.2.15

- \(\ce{Mg(OH)2}(s)+\ce{2HClO4}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Mg^2+}(aq)+\ce{2ClO4-}(aq)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\);

- \(\ce{SO3}(g)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\rightarrow \ce{H3O+}(aq)+\ce{HSO4-}(aq)\), (une solution de H 2 SO 4) ;

- \(\ce{SrO}(s)+\ce{H2SO4}(l)\rightarrow \ce{SrSO4}(s)+\ce{H2O}\)

Q4.2.16

Lorsqu'ils sont chauffés entre 700 et 800 °C, les diamants, qui sont du carbone pur, sont oxydés par l'oxygène atmosphérique. (Ils brûlent !) Écrivez l'équation équilibrée pour cette réaction.

Q4.2.17

L'armée a expérimenté des lasers qui produisent une lumière très intense lorsque le fluor se combine de manière explosive avec l'hydrogène. Quelle est l'équation équilibrée de cette réaction ?

ARTICLE 4.2.17

\(\ce{H2}(g)+\ce{F2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{2HF}(g)\)

Q4.2.18

Écrivez les équations moléculaires, ioniques totales et ioniques nettes pour les réactions suivantes :

- \(\ce{Ca(OH)2}(aq)+\ce{HC2H3O2}(aq)\rightarrow \)

- \(\ce{H3PO4}(aq)+\ce{CaCl2}(aq)\rightarrow \)

Q4.2.19

La Great Lakes Chemical Company produit du brome, Br 2, à partir de sels de bromure tels que le NaBr, dans la saumure de l'Arkansas en traitant la saumure avec du chlore gazeux. Écrivez une équation équilibrée pour la réaction du NaBr avec le Cl 2.

ARTICLE 4.2.19

\(\ce{2NaBr}(aq)+\ce{Cl2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{2NaCl}(aq)+\ce{Br2}(l)\)

Q4.2.20

Dans le cadre d'une expérience courante menée au laboratoire de chimie générale, le magnésium métallique est chauffé à l'air pour produire du MgO. Le MgO est un solide blanc, mais dans ces expériences, il apparaît souvent gris, en raison de petites quantités de Mg 3 N 2, un composé formé lors de la réaction d'une partie du magnésium avec l'azote. Écrivez une équation équilibrée pour chaque réaction.

Q4.2.21

L'hydroxyde de lithium peut être utilisé pour absorber le dioxyde de carbone dans des environnements fermés, tels que des engins spatiaux habités et des sous-marins. Écrivez une équation pour la réaction qui implique 2 moles de LiOH pour 1 mol de CO 2. (Conseil : l'eau est l'un des produits.)

ARTICLE 4.2.21

\(\ce{2LiOH}(aq)+\ce{CO2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{Li2CO3}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)\)

Q4.2.22

Du propionate de calcium est parfois ajouté au pain pour en retarder la détérioration. Ce composé peut être préparé par réaction du carbonate de calcium, CaCO 3, avec de l'acide propionique, C 2 H 5 CO 2 H, qui possède des propriétés similaires à celles de l'acide acétique. Écrivez l'équation équilibrée pour la formation du propionate de calcium.

Q4.2.23

Compléter et équilibrer les équations des réactions suivantes, dont chacune pourrait être utilisée pour éliminer le sulfure d'hydrogène du gaz naturel :

- \(\ce{Ca(OH)2}(s)+\ce{H2S}(g) \rightarrow\)

- \(\ce{Na2CO3}(aq)+\ce{H2S}(g)\rightarrow \)

ARTICLE 4.2.23

- \(\ce{Ca(OH)2}(s)+\ce{H2S}(g)\rightarrow \ce{CaS}(s)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\);

- \(\ce{Na2CO3}(aq)+\ce{H2S}(g)\rightarrow \ce{Na2S}(aq)+\ce{CO2}(g)+\ce{H2O}(l)\)

Q4.2.24

Le sulfure de cuivre (II) est oxydé par l'oxygène moléculaire pour produire du trioxyde de soufre gazeux et de l'oxyde de cuivre (II) solide. Le produit gazeux réagit ensuite avec de l'eau liquide pour produire du sulfate d'hydrogène liquide comme seul produit. Écrivez les deux équations qui représentent ces réactions.

Q4.2.25

Écrivez des équations chimiques équilibrées pour les réactions utilisées pour préparer chacun des composés suivants à partir de la ou des matières de départ données. Dans certains cas, des réactifs supplémentaires peuvent être nécessaires.

- nitrate d'ammonium solide à partir d'azote moléculaire gazeux par un procédé en deux étapes (d'abord réduire l'azote en ammoniac, puis neutraliser l'ammoniac avec un acide approprié)

- bromure d'hydrogène gazeux à partir de brome moléculaire liquide via une réaction redox en une étape

- H 2 S gazeux à partir de Zn et S solides via un procédé en deux étapes (d'abord une réaction redox entre les matières premières, puis une réaction du produit avec un acide fort)

ARTICLE 4.2.25

- étape 1 :\(\ce{N2}(g)+\ce{3H2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{2NH3}(g)\), étape 2 :\(\ce{NH3}(g)+\ce{HNO3}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{NH4NO3}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{NH4NO3}(s)\ce{(after\: drying)}\) ;

- \(\ce{H2}(g)+\ce{Br2}(l)\rightarrow \ce{2HBr}(g)\);

- \(\ce{Zn}(s)+\ce{S}(s)\rightarrow \ce{ZnS}(s)\)et\(\ce{ZnS}(s)+\ce{2HCl}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{ZnCl2}(aq)+\ce{H2S}(g)\)

Q4.2.26

Le cyclamate de calcium Ca (C 6 H 11 NHSO 3) 2 est un édulcorant artificiel utilisé dans de nombreux pays du monde mais interdit aux États-Unis. Il peut être purifié industriellement en le transformant en sel de baryum par réaction de l'acide C 6 H 11 NHSO 3 H avec du carbonate de baryum, traitement à l'acide sulfurique (le sulfate de baryum est très insoluble), puis neutralisation avec de l'hydroxyde de calcium. Écrivez les équations équilibrées pour ces réactions.

Q4.2.27

Terminez et équilibrez chacune des demi-réactions suivantes (étapes 2 à 5 de la méthode des demi-réactions) :

- \(\ce{Sn^4+}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Sn^2+}(aq)\)

- \(\ce{[Ag(NH3)2]+}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Ag}(s)+\ce{NH3}(aq)\)

- \(\ce{Hg2Cl2}(s)\rightarrow \ce{Hg}(l)+\ce{Cl-}(aq)\)

- \(\ce{H2O}(l)\rightarrow \ce{O2}(g)\ce{\:(in\: acidic\: solution)}\)

- \(\ce{IO3-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{I2}(s)\)

- \(\ce{SO3^2-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{SO4^2-}(aq)\ce{\:(in\: acidic\: solution)}\)

- \(\ce{MnO4-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Mn^2+}(aq)\ce{\:(in\: acidic\: solution)}\)

- \(\ce{Cl-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{ClO3-}(aq)\ce{\:(in\: basic\: solution)}\)

ARTICLE 4.2.27

- \(\ce{Sn^4+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}\rightarrow \ce{Sn^2+}(aq)\),

- \(\ce{[Ag(NH3)2]+}(aq)+ \ce{e-} \rightarrow \ce{Ag}(s)+\ce{2NH3}(aq)\);

- \(\ce{Hg2Cl2}(s)+ \ce{2e-} \rightarrow \ce{2Hg}(l)+\ce{2Cl-}(aq)\);

- \(\ce{2H2O}(l)\rightarrow \ce{O2}(g)+\ce{4H+}(aq)+\ce{4e-}\);

- \(\ce{6H2O}(l)+\ce{2IO3-}(aq)+\ce{10e-}\rightarrow \ce{I2}(s)+\ce{12OH-}(aq)\);

- \(\ce{H2O}(l)+\ce{SO3^2-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{SO4^2-}(aq)+\ce{2H+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}\);

- (g)\(\ce{8H+}(aq)+\ce{MnO4-}(aq)+\ce{5e-}\rightarrow \ce{Mn^2+}(aq)+\ce{4H2O}(l)\) ;

- (h)\(\ce{Cl-}(aq)+\ce{6OH-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{ClO3-}(aq)+\ce{3H2O}(l)+\ce{6e-}\)

Q4.2.28

Terminez et équilibrez chacune des demi-réactions suivantes (étapes 2 à 5 de la méthode des demi-réactions) :

- \(\ce{Cr^2+}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Cr^3+}(aq)\)

- \(\ce{Hg}(l)+\ce{Br-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{HgBr4^2-}(aq)\)

- \(\ce{ZnS}(s)\rightarrow \ce{Zn}(s)+\ce{S^2-}(aq)\)

- \(\ce{H2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{H2O}(l)\ce{\:(in\: basic\: solution)}\)

- \(\ce{H2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{H3O+}(aq)\ce{\:(in\: acidic\: solution)}\)

- \(\ce{NO3-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{HNO2}(aq)\ce{\:(in\: acidic\: solution)}\)

- \(\ce{MnO2}(s)\rightarrow \ce{MnO4-}(aq)\ce{\:(in\: basic\: solution)}\)

- \(\ce{Cl-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{ClO3-}(aq)\ce{\:(in\: acidic\: solution)}\)

Q4.2.29

Équilibrer chacune des équations suivantes selon la méthode des demi-réactions :

- \(\ce{Sn^2+}(aq)+\ce{Cu^2+}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Sn^4+}(aq)+\ce{Cu+}(aq)\)

- \(\ce{H2S}(g)+\ce{Hg2^2+}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Hg}(l)+\ce{S}(s)\ce{\:(in\: acid)}\)

- \(\ce{CN-}(aq)+\ce{ClO2}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{CNO-}(aq)+\ce{Cl-}(aq)\ce{\:(in\: acid)}\)

- \(\ce{Fe^2+}(aq)+\ce{Ce^4+}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Fe^3+}(aq)+\ce{Ce^3+}(aq)\)

- \(\ce{HBrO}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Br-}(aq)+\ce{O2}(g)\ce{\:(in\: acid)}\)

ARTICLE 4.2.29

- \(\ce{Sn^2+}(aq)+\ce{2Cu^2+}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Sn^4+}(aq)+\ce{2Cu+}(aq)\);

- \(\ce{H2S}(g)+\ce{Hg2^2+}(aq)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\rightarrow \ce{2Hg}(l)+\ce{S}(s)+\ce{2H3O+}(aq)\);

- \(\ce{5CN-}(aq)+\ce{2ClO2}(aq)+\ce{3H2O}(l)\rightarrow \ce{5CNO-}(aq)+\ce{2Cl-}(aq)+\ce{2H3O+}(aq)\);

- \(\ce{Fe^2+}(aq)+\ce{Ce^4+}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Fe^3+}(aq)+\ce{Ce^3+}(aq)\);

- \(\ce{2HBrO}(aq)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\rightarrow \ce{2H3O+}(aq)+\ce{2Br-}(aq)+\ce{O2}(g)\)

Q4.2.30

Équilibrer chacune des équations suivantes selon la méthode des demi-réactions :

- \(\ce{Zn}(s)+\ce{NO3-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Zn^2+}(aq)+\ce{N2}(g)\ce{\:(in\: acid)}\)

- \(\ce{Zn}(s)+\ce{NO3-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Zn^2+}(aq)+\ce{NH3}(aq)\ce{\:(in\: base)}\)

- \(\ce{CuS}(s)+\ce{NO3-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Cu^2+}(aq)+\ce{S}(s)+\ce{NO}(g)\ce{\:(in\: acid)}\)

- \(\ce{NH3}(aq)+\ce{O2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{NO2}(g)\ce{\:(gas\: phase)}\)

- \(\ce{Cl2}(g)+\ce{OH-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Cl-}(aq)+\ce{ClO3-}(aq)\ce{\:(in\: base)}\)

- \(\ce{H2O2}(aq)+\ce{MnO4-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Mn^2+}(aq)+\ce{O2}(g)\ce{\:(in\: acid)}\)

- \(\ce{NO2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{NO3-}(aq)+\ce{NO2-}(aq)\ce{\:(in\: base)}\)

- \(\ce{Fe^3+}(aq)+\ce{I-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Fe^2+}(aq)+\ce{I2}(aq)\)

Q4.2.31

Équilibrer chacune des équations suivantes selon la méthode des demi-réactions :

- \(\ce{MnO4-}(aq)+\ce{NO2-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{MnO2}(s)+\ce{NO3-}(aq)\ce{\:(in\: base)}\)

- \(\ce{MnO4^2-}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{MnO4-}(aq)+\ce{MnO2}(s)\ce{\:(in\: base)}\)

- \(\ce{Br2}(l)+\ce{SO2}(g)\rightarrow \ce{Br-}(aq)+\ce{SO4^2-}(aq)\ce{\:(in\: acid)}\)

ARTICLE 4.2.31

- \(\ce{2MnO4-}(aq)+\ce{3NO2-}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)\rightarrow \ce{2MnO2}(s)+\ce{3NO3-}(aq)+\ce{2OH-}(aq)\);

- \(\ce{3MnO4^2-}(aq)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\rightarrow \ce{2MnO4-}(aq)+\ce{4OH-}(aq)+\ce{MnO2}(s)\ce{\:(in\: base)}\);

- \(\ce{Br2}(l)+\ce{SO2}(g)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\rightarrow \ce{4H+}(aq)+\ce{2Br-}(aq)+\ce{SO4^2-}(aq)\)

4.3 : Stœchiométrie des réactions

Q4.3.1

Rédigez l'équation équilibrée, puis décrivez les étapes nécessaires pour déterminer les informations demandées dans chacun des domaines suivants :

- Nombre de moles et masse de chlore, Cl 2, nécessaires pour réagir avec 10,0 g de sodium métallique, Na, pour produire du chlorure de sodium, NaCl.

- Le nombre de moles et la masse d'oxygène formés par la décomposition de 1,252 g d'oxyde de mercure (II).

- Nombre de moles et masse de nitrate de sodium, NaNO 3, nécessaires pour produire 128 g d'oxygène. (L'autre produit est NaNO 2.)

- Le nombre de moles et la masse de dioxyde de carbone formés par la combustion de 20,0 kg de carbone dans un excès d'oxygène.

- Le nombre de moles et la masse de carbonate de cuivre (II) nécessaires pour produire 1 500 kg d'oxyde de cuivre (II). (Le CO 2 est l'autre produit.)

Q4.3.2

Déterminez le nombre de moles et la masse requise pour chaque réaction de l'exercice.

4.3.2

0,435 mol de Na, 0,217 mol de Cl 2, 15,4 g de Cl 2 ; 0,005780 mol de HgO, 2,890 × 10 −3 mol d'O 2, 9,248 × 10 −2 g d'O 2 ; 8,00 mol de NaNO 3, 6,8 × 10 2 g de NaNO 3 ; 1665 mol de CO 2, 73,3 kg de CO 2 ; 18,86 mol de CuO, 2,330 kg de CuCO 3 ; 0,4580 mol de C 2 H 4 Br 2, 86,05 g de C 2 H 4 Br 2

Q4.3.3

Rédigez l'équation équilibrée, puis décrivez les étapes nécessaires pour déterminer les informations demandées dans chacun des domaines suivants :

- Le nombre de moles et la masse de Mg nécessaires pour réagir avec 5,00 g de HCl et produire du MgCl 2 et de l'H 2.

- Le nombre de moles et la masse d'oxygène formés par la décomposition de 1,252 g d'oxyde d'argent (I).

- Nombre de moles et masse de carbonate de magnésium, MgCO 3, nécessaires pour produire 283 g de dioxyde de carbone. (Le MgO est l'autre produit.)

- Le nombre de moles et la masse d'eau formés par la combustion de 20,0 kg d'acétylène, C 2 H 2, dans un excès d'oxygène.

- Le nombre de moles et la masse de peroxyde de baryum, BaO 2, nécessaires pour produire 2 500 kg d'oxyde de baryum, BaO (O 2 est l'autre produit).

Q4.3.4

Déterminez le nombre de moles et la masse requise pour chaque réaction de l'exercice.

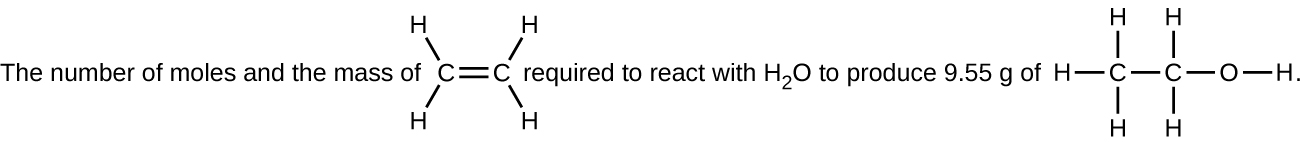

4.3.4

0,0686 mol de Mg, 1,67 g de Mg ; 2,701 × 10 −3 mol d'O 2, 0,08644 g d'O 2 ; 6,43 mol de MgCO 3, 542 g de MgCO 3 713 mol de H 2 O, 12,8 kg de H 2 O ; 16,31 mol de BaO 2, 2 762 g de BaO 2 ; 0,207 mol de C 2 H 4 , 5,81 g de C 2 H 4

Q4.3.5

L'H 2 est produit par la réaction de 118,5 mL d'une solution de H 3 PO 4 à 0,8775-M selon l'équation suivante :\(\ce{2Cr + 2H3PO4 \rightarrow 3H2 + 2CrPO4}\).

- Outline the steps necessary to determine the number of moles and mass of H2.

- Perform the calculations outlined.

S4.3.5

a.)

- Convert mL to L

- Multiply L by the molarity to determine moles of H3PO4

- Convert moles of H3PO4 to moles of H2

- Multiply moles of H2 by the molar mass of H2 to get the answer in grams

b.)

1. \(118.5\: mL\times \dfrac{1\: L}{1000\: mL} = 0.1185\: L\)

2. \(0.1185\: L \times \dfrac{0.8775\: moles\: \ce{H3PO4}}{1\: L} = 0.1040\: moles\: \ce{H3PO4}\)

3. \(0.1040\: moles\: \ce{H3PO4} \times \dfrac{3\: moles\:\ce{H_2}}{2\: moles\: \ce{H3PO4}} = 0.1560\: moles\: \ce{H2}\)

4. \(0.1560\: moles\: \ce{H2} \times \dfrac{2.02 g}{1\: mole} = 0.3151g\: \ce{H2}\)

Q4.3.6

Gallium chloride is formed by the reaction of 2.6 L of a 1.44 M solution of HCl according to the following equation: \(\ce{2Ga + 6HCl \rightarrow 2GaCl3 + 3H2}\).

- Outline the steps necessary to determine the number of moles and mass of gallium chloride.

- Perform the calculations outlined.

S4.3.6

\(\mathrm{volume\: HCl\: solution \rightarrow mol\: HCl \rightarrow mol\: GaCl_3}\); 1.25 mol GaCl3, 2.2 × 102 g GaCl3

Q4.3.7

I2 is produced by the reaction of 0.4235 mol of CuCl2 according to the following equation: \(\ce{2CuCl2 + 4KI \rightarrow 2CuI + 4KCl + I2}\).

- How many molecules of I2 are produced?

- What mass of I2 is produced?

Q4.3.8

Silver is often extracted from ores as K[Ag(CN)2] and then recovered by the reaction

\(\ce{2K[Ag(CN)2]}(aq)+\ce{Zn}(s)\rightarrow \ce{2Ag}(s)+\ce{Zn(CN)2}(aq)+\ce{2KCN}(aq)\)

- How many molecules of Zn(CN)2 are produced by the reaction of 35.27 g of K[Ag(CN)2]?

- What mass of Zn(CN)2 is produced?

S4.3.8

5.337 × 1022 molecules; 10.41 g Zn(CN)2

Q4.3.9

What mass of silver oxide, Ag2O, is required to produce 25.0 g of silver sulfadiazine, AgC10H9N4SO2, from the reaction of silver oxide and sulfadiazine?

\(\ce{2C10H10N4SO2 + Ag2O \rightarrow 2AgC10H9N4SO2 + H2O}\)

Q4.3.10

Carborundum is silicon carbide, SiC, a very hard material used as an abrasive on sandpaper and in other applications. It is prepared by the reaction of pure sand, SiO2, with carbon at high temperature. Carbon monoxide, CO, is the other product of this reaction. Write the balanced equation for the reaction, and calculate how much SiO2 is required to produce 3.00 kg of SiC.

S4.3.10

\(\ce{SiO2 + 3C \rightarrow SiC + 2CO}\), 4.50 kg SiO2

Q4.3.11

Automotive air bags inflate when a sample of sodium azide, NaN3, is very rapidly decomposed.

\(\ce{2NaN3}(s) \rightarrow \ce{2Na}(s) + \ce{3N2}(g)\)

What mass of sodium azide is required to produce 2.6 ft3 (73.6 L) of nitrogen gas with a density of 1.25 g/L?

S4.3.11

142g NaN3

Q4.3.12

Urea, CO(NH2)2, is manufactured on a large scale for use in producing urea-formaldehyde plastics and as a fertilizer. What is the maximum mass of urea that can be manufactured from the CO2 produced by combustion of 1.00×103 kg of carbon followed by the reaction?

\[\ce{CO2}(g)+\ce{2NH3}(g)\rightarrow \ce{CO(NH2)2}(s)+\ce{H2O}(l)\]

S4.3.12

5.00 × 103 kg

Q4.3.13

In an accident, a solution containing 2.5 kg of nitric acid was spilled. Two kilograms of Na2CO3 was quickly spread on the area and CO2 was released by the reaction. Was sufficient Na2CO3 used to neutralize all of the acid?

Q4.3.14

A compact car gets 37.5 miles per gallon on the highway. If gasoline contains 84.2% carbon by mass and has a density of 0.8205 g/mL, determine the mass of carbon dioxide produced during a 500-mile trip (3.785 liters per gallon).

S4.3.14

1.28 × 105 g CO2

Q4.3.15

What volume of a 0.750 M solution of hydrochloric acid, a solution of HCl, can be prepared from the HCl produced by the reaction of 25.0 g of NaCl with an excess of sulfuric acid?

\[\ce{NaCl}(s)+\ce{H2SO4}(l)\rightarrow \ce{HCl}(g)+\ce{NaHSO4}(s)\]

Q4.3.16

What volume of a 0.2089 M KI solution contains enough KI to react exactly with the Cu(NO3)2 in 43.88 mL of a 0.3842 M solution of Cu(NO3)2?

\[\ce{2Cu(NO3)2 + 4KI \rightarrow 2CuI + I2 + 4KNO3}\]

S4.3.16

161.40 mL KI solution

Q4.3.17

A mordant is a substance that combines with a dye to produce a stable fixed color in a dyed fabric. Calcium acetate is used as a mordant. It is prepared by the reaction of acetic acid with calcium hydroxide.

\[\ce{2CH3CO2H + Ca(OH)2 \rightarrow Ca(CH3CO2)2 + 2H2O}\]

What mass of Ca(OH)2 is required to react with the acetic acid in 25.0 mL of a solution having a density of 1.065 g/mL and containing 58.0% acetic acid by mass?

Q4.3.18

The toxic pigment called white lead, Pb3(OH)2(CO3)2, has been replaced in white paints by rutile, TiO2. How much rutile (g) can be prepared from 379 g of an ore that contains 88.3% ilmenite (FeTiO3) by mass?

\[\ce{2FeTiO3 + 4HCl + Cl2 \rightarrow 2FeCl3 + 2TiO2 + 2H2O}\]

S4.3.18

176 g TiO2

4.4: Reaction Yields

Q4.4.1

The following quantities are placed in a container: 1.5 × 1024 atoms of hydrogen, 1.0 mol of sulfur, and 88.0 g of diatomic oxygen.

- What is the total mass in grams for the collection of all three elements?

- What is the total number of moles of atoms for the three elements?

- If the mixture of the three elements formed a compound with molecules that contain two hydrogen atoms, one sulfur atom, and four oxygen atoms, which substance is consumed first?

- How many atoms of each remaining element would remain unreacted in the change described in ?

Q4.4.2

What is the limiting reactant in a reaction that produces sodium chloride from 8 g of sodium and 8 g of diatomic chlorine?

S4.4.2

The limiting reactant is Cl2.

Q4.4.3

Which of the postulates of Dalton's atomic theory explains why we can calculate a theoretical yield for a chemical reaction?

Q4.4.4

A student isolated 25 g of a compound following a procedure that would theoretically yield 81 g. What was his percent yield?

S4.4.4

\(\mathrm{Percent\: yield = 31\%}\)

Q4.4.5

A sample of 0.53 g of carbon dioxide was obtained by heating 1.31 g of calcium carbonate. What is the percent yield for this reaction?

\[\ce{CaCO3}(s)\rightarrow \ce{CaO}(s)+\ce{CO2}(s)\]

Q4.4.6

Freon-12, CCl2F2, is prepared from CCl4 by reaction with HF. The other product of this reaction is HCl. Outline the steps needed to determine the percent yield of a reaction that produces 12.5 g of CCl2F2 from 32.9 g of CCl4. Freon-12 has been banned and is no longer used as a refrigerant because it catalyzes the decomposition of ozone and has a very long lifetime in the atmosphere. Determine the percent yield.

S4.4.6

\(\ce{g\: CCl4\rightarrow mol\: CCl4\rightarrow mol\: CCl2F2 \rightarrow g\: CCl2F2}, \mathrm{\:percent\: yield=48.3\%}\)

Q4.4.7

Citric acid, C6H8O7, a component of jams, jellies, and fruity soft drinks, is prepared industrially via fermentation of sucrose by the mold Aspergillus niger. The equation representing this reaction is

\[\ce{C12H22O11 + H2O + 3O2 \rightarrow 2C6H8O7 + 4H2O}\]

What mass of citric acid is produced from exactly 1 metric ton (1.000 × 103 kg) of sucrose if the yield is 92.30%?

Q4.4.8

Toluene, C6H5CH3, is oxidized by air under carefully controlled conditions to benzoic acid, C6H5CO2H, which is used to prepare the food preservative sodium benzoate, C6H5CO2Na. What is the percent yield of a reaction that converts 1.000 kg of toluene to 1.21 kg of benzoic acid?

\[\ce{2C6H5CH3 + 3O2 \rightarrow 2C6H5CO2H + 2H2O}\]

S4.4.8

\(\mathrm{percent\: yield=91.3\%}\)

Q4.4.9

In a laboratory experiment, the reaction of 3.0 mol of H2 with 2.0 mol of I2 produced 1.0 mol of HI. Determine the theoretical yield in grams and the percent yield for this reaction.

Q4.4.10

Outline the steps needed to solve the following problem, then do the calculations. Ether, (C2H5)2O, which was originally used as an anesthetic but has been replaced by safer and more effective medications, is prepared by the reaction of ethanol with sulfuric acid.

2C2H5OH + H2SO4 ⟶ (C2H5)2 + H2SO4·H2O

Q4.4.11

What is the percent yield of ether if 1.17 L (d = 0.7134 g/mL) is isolated from the reaction of 1.500 L of C2H5OH (d = 0.7894 g/mL)?

S4.4.11

Convert mass of ethanol to moles of ethanol; relate the moles of ethanol to the moles of ether produced using the stoichiometry of the balanced equation. Convert moles of ether to grams; divide the actual grams of ether (determined through the density) by the theoretical mass to determine the percent yield; 87.6%

Q4.4.12

Outline the steps needed to determine the limiting reactant when 30.0 g of propane, C3H8, is burned with 75.0 g of oxygen.

\[\mathrm{percent\: yield=\dfrac{0.8347\:\cancel{g}}{0.9525\:\cancel{g}}\times 100\%=87.6\%}\]

Determine the limiting reactant.

Q4.4.13

Outline the steps needed to determine the limiting reactant when 0.50 g of Cr and 0.75 g of H3PO4 react according to the following chemical equation?

\[\ce{2Cr + 2H3PO4 \rightarrow 2CrPO4 + 3H2}\]

Determine the limiting reactant.

S4.4.13

The conversion needed is \(\ce{mol\: Cr \rightarrow mol\: H2PO4}\). Then compare the amount of Cr to the amount of acid present. Cr is the limiting reactant.

Q4.4.14

What is the limiting reactant when 1.50 g of lithium and 1.50 g of nitrogen combine to form lithium nitride, a component of advanced batteries, according to the following unbalanced equation?

\[\ce{Li + N2 \rightarrow Li3N}\]

S4.4.14

\[\ce{6Li} + \ce{N2} \rightarrow \: \ce{2Li3N}\]

\[1.50g\: \ce{Li} \times \dfrac{1\: mole\: \ce{Li}}{6.94g\: \ce{Li}} \times\dfrac{2\: mole\: \ce{Li3N}}{6\:mole\: \ce{Li}} = 0.0720\: moles\: \ce{Li3N}\]

\[1.50g\: \ce{N2} \times \dfrac{1\: mole\: \ce{N2}}{28.02g\: \ce{N2}} \times\dfrac{2\: mole\: \ce{Li3N}}{1\:mole\: \ce{N2}} = 0.107\: moles\: \ce{Li3N}\]

\(\ce{Li}\) is the limiting reactant

Q4.4.15

Uranium can be isolated from its ores by dissolving it as UO2(NO3)2, then separating it as solid UO2(C2O4)·3H2O. Addition of 0.4031 g of sodium oxalate, Na2C2O4, to a solution containing 1.481 g of uranyl nitrate, UO2(NO2)2, yields 1.073 g of solid UO2(C2O4)·3H2O.

\[\ce{Na2C2O4 + UO2(NO3)2 + 3H2O ⟶ UO2(C2O4)·3H2O + 2NaNO3}\]

Determine the limiting reactant and the percent yield of this reaction.

S4.4.15

Na2C2O4 is the limiting reactant. percent yield = 86.6%

Q4.4.16

How many molecules of C2H4Cl2 can be prepared from 15 C2H4 molecules and 8 Cl2 molecules?

Q4.4.17

How many molecules of the sweetener saccharin can be prepared from 30 C atoms, 25 H atoms, 12 O atoms, 8 S atoms, and 14 N atoms?

S4.4.17

Only four molecules can be made.

Q4.4.18

The phosphorus pentoxide used to produce phosphoric acid for cola soft drinks is prepared by burning phosphorus in oxygen.

- What is the limiting reactant when 0.200 mol of P4 and 0.200 mol of O2 react according to \[\ce{P4 + 5O2 \rightarrow P4O10}\]

- Calculate the percent yield if 10.0 g of P4O10 is isolated from the reaction.

Q4.4.19

Would you agree to buy 1 trillion (1,000,000,000,000) gold atoms for $5? Explain why or why not. Find the current price of gold at http://money.cnn.com/data/commodities/ \(\mathrm{(1\: troy\: ounce=31.1\: g)}\)

S4.4.19

This amount cannot be weighted by ordinary balances and is worthless.

4.5: Quantitative Chemical Analysis

Q4.5.1

What volume of 0.0105-M HBr solution is be required to titrate 125 mL of a 0.0100-M Ca(OH)2 solution?

\[\ce{Ca(OH)2}(aq)+\ce{2HBr}(aq) \rightarrow \ce{CaBr2}(aq)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\]

Q4.5.2

Titration of a 20.0-mL sample of acid rain required 1.7 mL of 0.0811 M NaOH to reach the end point. If we assume that the acidity of the rain is due to the presence of sulfuric acid, what was the concentration of sulfuric acid in this sample of rain?

S4.5.2

3.4 × 10−3 M H2SO4

Q4.5.3

What is the concentration of NaCl in a solution if titration of 15.00 mL of the solution with 0.2503 M AgNO3 requires 20.22 mL of the AgNO3 solution to reach the end point?

\[\ce{AgNO3}(aq)+\ce{NaCl}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{AgCl}(s)+\ce{NaNO3}(aq)\]

Q4.5.4

In a common medical laboratory determination of the concentration of free chloride ion in blood serum, a serum sample is titrated with a Hg(NO3)2 solution.

\[\ce{2Cl-}(aq)+\ce{Hg(NO3)2}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{2NO3-}(aq)+\ce{HgCl2}(s)\]

What is the Cl− concentration in a 0.25-mL sample of normal serum that requires 1.46 mL of 5.25 × 10−4 M Hg(NO3)2(aq) to reach the end point?

S4.5.4

9.6 × 10−3 M Cl−

Q4.5.5

Potatoes can be peeled commercially by soaking them in a 3-M to 6-M solution of sodium hydroxide, then removing the loosened skins by spraying them with water. Does a sodium hydroxide solution have a suitable concentration if titration of 12.00 mL of the solution requires 30.6 mL of 1.65 M HCI to reach the end point?

Q4.5.6

A sample of gallium bromide, GaBr2, weighing 0.165 g was dissolved in water and treated with silver nitrate, AgNO3, resulting in the precipitation of 0.299 g AgBr. Use these data to compute the %Ga (by mass) GaBr2.

S4.5.6

22.4%

Q4.5.7

The principal component of mothballs is naphthalene, a compound with a molecular mass of about 130 amu, containing only carbon and hydrogen. A 3.000-mg sample of naphthalene burns to give 10.3 mg of CO2. Determine its empirical and molecular formulas.

Q4.5.8

A 0.025-g sample of a compound composed of boron and hydrogen, with a molecular mass of ~28 amu, burns spontaneously when exposed to air, producing 0.063 g of B2O3. What are the empirical and molecular formulas of the compound.

S4.5.8

The empirical formula is BH3. The molecular formula is B2H6.

Q4.5.9

Sodium bicarbonate (baking soda), NaHCO3, can be purified by dissolving it in hot water (60 °C), filtering to remove insoluble impurities, cooling to 0 °C to precipitate solid NaHCO3, and then filtering to remove the solid, leaving soluble impurities in solution. Any NaHCO3 that remains in solution is not recovered. The solubility of NaHCO3 in hot water of 60 °C is 164 g L. Its solubility in cold water of 0 °C is 69 g/L. What is the percent yield of NaHCO3 when it is purified by this method?

Q4.5.10

What volume of 0.600 M HCl is required to react completely with 2.50 g of sodium hydrogen carbonate?

\[\ce{NaHCO3}(aq)+\ce{HCl}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{NaCl}(aq)+\ce{CO2}(g)+\ce{H2O}(l)\]

S4.5.10

49.6 mL

Q4.5.11

What volume of 0.08892 M HNO3 is required to react completely with 0.2352 g of potassium hydrogen phosphate?

\[\ce{2HNO3}(aq)+\ce{K2HPO4}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{H2PO4}(aq)+\ce{2KNO3}(aq)\]

Q4.5.12

What volume of a 0.3300-M solution of sodium hydroxide would be required to titrate 15.00 mL of 0.1500 M oxalic acid?

\[\ce{C2O4H2}(aq)+\ce{2NaOH}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{Na2C2O4}(aq)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\]

S4.5.12

13.64 mL

Q4.5.13

What volume of a 0.00945-M solution of potassium hydroxide would be required to titrate 50.00 mL of a sample of acid rain with a H2SO4 concentration of 1.23 × 10−4 M.

\[\ce{H2SO4}(aq)+\ce{2KOH}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{K2SO4}(aq)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\]

S4.5.13

1.30 mL

Q4.5.14

A sample of solid calcium hydroxide, Ca(OH)2, is allowed to stand in water until a saturated solution is formed. A titration of 75.00 mL of this solution with 5.00 × 10−2 M HCl requires 36.6 mL of the acid to reach the end point.

\[\ce{Ca(OH)2}(aq)+\ce{2HCl}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{CaCl2}(aq)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\]

What is the molarity?

S4.5.14

1.22 M

Q4.5.15

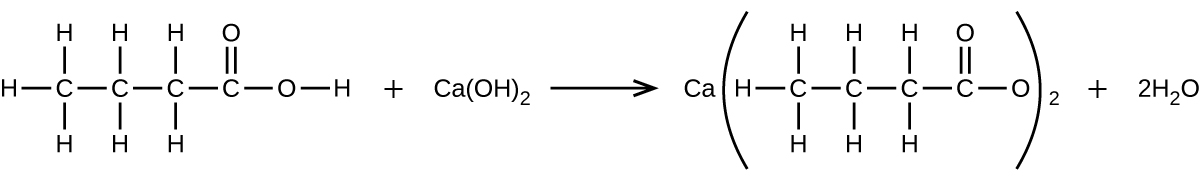

What mass of Ca(OH)2 will react with 25.0 g of propionic acid to form the preservative calcium propionate according to the equation?

Q4.5.16

How many milliliters of a 0.1500-M solution of KOH will be required to titrate 40.00 mL of a 0.0656-M solution of H3PO4?

\[\ce{H3PO4}(aq)+\ce{2KOH}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{K2HPO4}(aq)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\]

S4.5.16

34.99 mL KOH

Q4.5.17

Potassium acid phthalate, KHC6H4O4, or KHP, is used in many laboratories, including general chemistry laboratories, to standardize solutions of base. KHP is one of only a few stable solid acids that can be dried by warming and weighed. A 0.3420-g sample of KHC6H4O4 reacts with 35.73 mL of a NaOH solution in a titration. What is the molar concentration of the NaOH?

\[\ce{KHC6H4O4}(aq)+\ce{NaOH}(aq)\rightarrow \ce{KNaC6H4O4}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(aq)\]

Q4.5.18

The reaction of WCl6 with Al at ~400 °C gives black crystals of a compound containing only tungsten and chlorine. A sample of this compound, when reduced with hydrogen, gives 0.2232 g of tungsten metal and hydrogen chloride, which is absorbed in water. Titration of the hydrochloric acid thus produced requires 46.2 mL of 0.1051 M NaOH to reach the end point. What is the empirical formula of the black tungsten chloride?

S4.5.19

The empirical formula is WCl4.