9.3:解释社会运动的框架

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 172039

- Dino Bozonelos, Julia Wendt, Charlotte Lee, Jessica Scarffe, Masahiro Omae, Josh Franco, Byran Martin, & Stefan Veldhuis

- Victor Valley College, Berkeley City College, Allan Hancock College, San Diego City College, Cuyamaca College, Houston Community College, and Long Beach City College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

学习目标

在本节结束时,您将能够:

- 评估解释社交运动出现和成功的几个因素的框架

- 认识其他因素的影响,例如国际影响和非暴力策略

导言

社会运动往往体现雄心壮志,没有集体行动就无法实现。 二十一世纪见证了无数社会运动的兴起,从阻止气候变化的日出运动到 #metoo 争取妇女权利运动和争取种族正义的 Black Lives Matter 运动。 保守的社会运动包括新基督教右翼和全球新右翼运动。 尽管起因和参与者差异很大,但学者们试图找出社会运动中的共同因素,并解释社会运动可能在哪些条件下实现其目标。

社会运动研究是一项跨学科的事业。 社会科学家利用其学科工具来理解集体动员的复杂出现。 心理学家将重点放在个人分析层面上,而社会学家和政治学家则关注促成或刺激社交运动的群体动态和制度因素。 理解社会运动的一个框架侧重于三个主要因素:机会、组织和框架。

政治机会

法国小说家兼诗人维克多·雨果(Victor Hugo)认为:“没有什么比时机成熟的想法更有力的了。” 将这种充满希望的见解应用于倡导某项事业的社交运动时,背景很重要。 只有当某些星星对齐时,思想觉醒的时刻才可能带来具体的变化。 学者们发现,当更广泛的政治背景能够接受社会运动所提倡的思想时,社会运动更有可能出现并占上风。 当政治精英们讨论气候变化问题时,富裕民主国家的街头倡导势头增强;当民选官员表示愿意改变长期存在的禁止性行为法律的政策时,美国同性恋权利运动的势头最大少数民族。

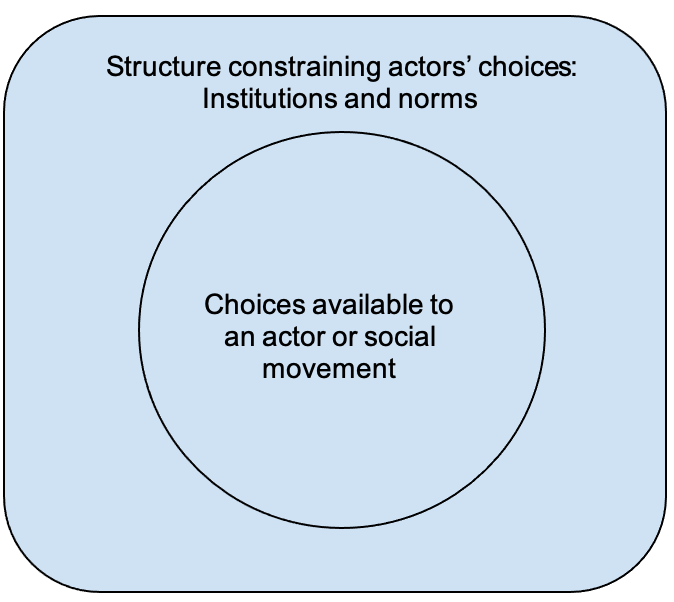

因此,政治机会是一个结构性因素,它影响社会运动是否形成以及是否可能在其目标中占上风。 这里的@@ 结构是指在特定时刻发挥作用的更大社会力量:限制个人行为的制度和规范,或广泛认同的信念和实践。 结构可以包括政治机构和精英是否愿意接受具体的变化,社会是否接受社会运动所倡导的信息和策略。 正如大卫·迈耶所说,激进分子必须有 “政体中的宽容空间”(2004,第128页)。 而且,社会决不能过多地压制活动分子,以至于他们缺乏提出投诉的词汇或手段。 结构是社会运动可能形成并推动变革的背景。 在这个结构中,活动家可以从一系列有关如何组织、动员和制定目标的策略中进行选择(见下图)。

In the case of the US Civil Rights Movement that unfolded during the mid-twentieth century, markers of political opportunity can be identified in hindsight. These include the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling by the US Supreme Court, which declared unconstitutional the segregation of schools by race. Political leaders also signaled an opening, evident in public addresses such as President John F. Kennedy’s 1963 Report to the People on American Civil Rights, in which he declared, “It ought to be possible, in short, for every American to enjoy the privileges of being American without regard to his race or his color.” Such events signaled that powerful formal institutions were willing to change, and the time was ripe for a social movement to activate and accelerate that change.

Organization and mobilization

While the emergence of a political opening is key, a social moment cannot be sustained without strong organizational structures in place. As Lenin observed, a revolution will succeed when carried out by a vanguard party that offers an “organizational weapon” by which revolutionaries may strike down existing institutions. Successful communist party movements, such as those in Russia, China, and Cuba, relied on disciplined, hierarchical party organizations that reached down to cells of activists at the grassroots level.

More contemporary social movements need not have such extreme organization, but organizational strength is a direct correlate of mobilizational power and momentum. Douglas McAdam has studied several key organizations that facilitated the successes of the US Civil Rights Movement of the mid-twentieth century. These backbone organizations included Black churches, Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Black churches contained multigenerational communities united by bonds of faith and trust; HBCUs offered spaces for student organizing; the NAACP provided organizational and political resources to advance civil rights through mass protests, coordinated activities, and legal action. All of these organizations had proven capacity for carrying out complex community actions under adverse circumstances; they were also spaces for pooling resources and communicating initiatives to a relatively large audience of proven and potential activists (McAdam 1999).

Organizational forms may be more decentralized and less hierarchical by design. The “leaderless” Black Lives Matter movement in the US is an example of this: there is no singular set of charismatic leading figures such as Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, Huey P. Newton or Bobby Seale to set the tone and agenda. Local actions are organized and executed without direction from an organizational headquarters. One strength of this evolution in the organization of a social movement is more cellular organization, with new protest repertoires and messages emerging to suit local conditions and audiences. A disadvantage is the potential for the movement to lose momentum without clearly articulated and unifying goals.

New information and communication technologies (ICT) have changed the ways a social movement might organize and mobilize. By the dawn of the twenty-first century, there was optimism regarding the possibilities for uniting activists via social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter (Diamond and Plattner 2012). So-called “liberation technologies” were heralded as a means to organize a social movement in defiance of geographical constraints and even repressive governments. However, this initial optimism has been followed by critiques of these new technologies as leading to “armchair activism” by individuals unwilling to invest real resources into a social movement. Social media platforms have also proven unruly spaces for organizing due to the challenges of misinformation, government interference, and weak bonds of trust between participants. The impact of ICT on the emergence and success of a social movement has thus yielded mixed results.

Framing

Political opportunity, organization, and mobilizational capacity are complemented by the framing of an issue. Framing refers to the ways in which a social problem is defined by, presented to and resonates with members of a social movement and society more broadly. Framing is a key strategic move because the chosen frames must be culturally appropriate and meaningful.

The concept of frames explicitly brings a psychological and emotional element into our understanding of social movements: individuals join because of an affinity for the cause rather than merely out of rational self-interest (Goodwin, Jasper, and Polletta 2001). They must actively engage in “sense making” and determine for themselves, as well as fellow activists, their purpose and goals. Framing can incite emotions such as anger over a perceived injustice but also psychological safety in the belief that one is part of a larger community with shared beliefs.

Framing takes place at the inception of a social movement. It can sustain the movement and attract additional adherents from society. Framing is critical when we consider how the modern environmental movement in the US was galvanized by publications such as Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring, which offered an evocative and powerful vision (a lifeless natural landscape) for understanding ecological disaster through the concrete example of overuse of chemical pesticides. This book helped to frame the problem and invoke the shock, anger, and anxieties that are part of the modern environmental justice movement.

International influences

Many of the causes embraced by social movements span countries, regions and the globe. Given the advent of globalization since the end of the Cold War in 1991, seemingly faraway events may resonate with global audiences: deforestation in Indonesia sparks protests in European cities over unsustainable practices in the supply chains of furniture companies that source wood from Borneo. Environmental activists in Indonesia thus find common cause with counterparts in the Netherlands. Social movements may diffuse across borders, with activists sharing tactics, resources, and providing moral support to one another in their common cause. Diffusion is defined as the spread of an idea, movement, tactics, strategies, and other resources across international borders. One prominent example of international diffusion is the spread of liberal democracy around the globe in the decades spanning the 1990s to the 2000s.

International "democracy promotion" efforts are one driver of this worldwide increase in democracy since the 1990s, whereby international resources are directed toward pro-democracy domestic social movements. These have been led by wealthy democracies (such as those of North America, the Antipodes, the EU, and Japan) to strengthen younger democracies worldwide. Democracy promotion can include a wide range of activities such as government-supported grants to pro-democracy activists in other countries, nonprofit exchanges of information and expertise, and more horizontal exchanges of knowledge and resources between democracy activists worldwide. Pro-democracy movements in countries as varied as Ukraine and Nicaragua receive support from international donors and advisors.

The role of nonviolence

There are consequences to the tactics chosen by social movement leaders and participants. The range of tactics that a social movement may employ is vast, and social movements are constantly innovating and creating new repertoires based on changing contexts, cultural symbols, and new technologies. New strategies emerge with each social movement. Pro-democracy Hong Kong protesters, as part of their movement to secure democratic rights and autonomy within the People’s Republic of China’s “One Country, Two Systems” framework, created new forms of protest in 2019. One notable tactic was occupying terminals of Hong Kong International Airport. This served to disrupt the business of a global city reliant on the flow of businesspeople and tourists by air and draw global attention to their plight.

These protestors and others opted for nonviolent strategies of protest, a tradition which has deep roots in various faith traditions dating back millennia. More recently, social movement leaders ranging from Mohandas K. Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr., have made significant philosophical contributions and practical applications of nonviolence to movements for social change.

Empirical research comparing nonviolent and violent resistance campaigns has found that nonviolent campaigns are twice as successful as their violent counterparts (53 percent compared with 26 percent) (Stephan and Chenoweth 2008). Note that campaigns are defined by Stephan and Chenoweth as “major nonstate rebellions … [which include] a series of repetitive, durable, organized, and observable events directed at a certain target to achieve a goal,” (2008, p. 8).

The success of nonviolent social movements is attributed to various factors. It is due to higher public perceptions of the legitimacy of nonviolent movements as well as greater public sympathy for movements committed to principles of nonviolence. Nonviolent movements also constrain government responses, as suppressing a nonviolent movement with force can drive public support -- domestic and international -- even more toward the aims of the social movement.