45.2: 生活史和自然选择

- Page ID

- 203007

培养技能

- 描述自然选择如何影响生活史模式

- 解释不同的生活史模式以及不同的繁殖策略如何影响物种的生存

物种的生活史描述了其生命周期中发生的一系列事件,例如如何分配资源用于生长、维持和繁殖。 生命史特征影响生物体的生命表。 一个物种的生命史是由环境和自然选择遗传决定和塑造的。

生活史模式和能量预算

所有活生物体的生长、维持和繁殖都需要能量;同时,能量通常是决定生物存活的主要限制因素。 例如,植物通过光合作用从太阳获取能量,但必须消耗这种能量来生长、维持健康和生产能量丰富的种子以培育下一代。 动物在使用部分能量储备来获取食物方面还有额外的负担。 此外,有些动物必须消耗精力来照顾它们的后代。 因此,所有物种都有能量预算:它们必须平衡能量摄入与新陈代谢、繁殖、育儿和能量储存(例如熊为冬眠积聚体内脂肪)的能量消耗。

育儿与生育能力

生@@ 育力是人群中个体的潜在生殖能力。 换句话说,生殖力描述了如果一个人有尽可能多的后代,在后代出生后尽快重复繁殖周期,理想情况下可以产生多少后代。 在动物中,生育能力与父母对单个后代的照顾量成反比。 产生许多后代的物种,例如许多海洋无脊椎动物,通常对后代几乎没有照顾(无论如何它们都没有足够的能量或能力)。 他们的大部分能源预算都用于生育许多微小的后代。 采用这种策略的动物通常在很小的时候就能自给自足。 这是因为这些生物为了最大限度地提高其进化适应性而做出了能量权衡。 因为他们的能量被用来培养后代而不是父母的照顾,所以这些后代有一定的能力能够在自己的环境中移动,寻找食物甚至庇护所,这是有道理的。 即使有了这些能力,它们的小体积也使它们极易受到捕食,因此,许多后代的产生使它们中有足够多的后代能够存活以维持物种。

繁殖期间后代很少的动物物种通常会给予父母广泛的照顾,将大部分精力预算用于这些活动,有时以牺牲自身的健康为代价。 许多哺乳动物就是这种情况,例如人类、袋鼠和熊猫。 这些物种的后代在出生时相对无助,需要发育才能实现自给自足。

生殖力低的植物几乎不会产生能量丰富的种子(例如椰子和栗子),每种种子都有很好的机会发芽成新的生物;生育力高的植物通常有许多能量匮乏的小种子(如兰花),存活几率相对较低。 尽管看来椰子和栗子的存活机会更大,但兰花的能量权衡也非常有效。 这取决于能量在哪里使用,用于大量种子,或者用更多的能量减少种子。

繁殖早期与晚期繁殖

生命史中的繁殖时间也会影响物种的存活。 在早期繁殖的生物产生后代的机会更大,但这通常是以牺牲其生长和维持健康为代价的。 相反,在生命晚年开始繁殖的生物通常具有更高的生育能力或更有能力提供父母照顾,但它们冒着无法存活到育龄的风险。 这方面的例子可以在鱼类中看到。 像孔雀鱼这样的小鱼利用它们的能量来快速繁殖,但永远无法达到可以抵御某些掠食者的体型。 较大的鱼,比如蓝鳃鱼或鲨鱼,会消耗它们的能量来获得较大的体型,但这样做有在繁殖或至少繁殖到最大限度之前死亡的风险。 这些不同的能量策略和权衡是理解每个物种进化的关键,因为它可以最大限度地提高其适应性并填补其利基市场。 在能源预算方面,一些物种 “全力以赴”,并在死亡之前尽早耗尽大部分能量储备进行繁殖。 其他物种延迟繁殖,以便成为更强壮、更有经验的个体,并确保它们足够强壮,可以在必要时提供父母照顾。

单次生殖事件与多次生殖事件

一些生活史特征,例如生育能力、繁殖时机和父母的照顾,可以归纳为可供多个物种使用的通用策略。 当一个物种在其一生中只繁殖一次然后死亡时,就会发生 Semel parity。 这些物种在一次繁殖活动中消耗了大部分资源预算,牺牲了它们的生命值以至于它们无法生存。 semelparity 的例子是竹子,它开花一次然后死亡,还有奇努克鲑鱼(图\(\PageIndex{1}\) a),它利用其大部分能量储备从海洋迁移到淡水筑巢区,在那里繁殖然后死亡。 科学家们对奇努克人繁殖后死亡的进化优势提出了其他解释:由大量释放皮质类固醇激素引起的程序性自杀,大概是为了让父母成为后代的食物,或者仅仅是由于孩子的能量需求而导致的精疲力尽复制;这些问题仍在争论之中。

Interoparity 描述了在其生命中反复繁殖的物种。 有些动物每年只能交配一次,但可以存活多个交配季节。 叉角羚是动物进入季节性发情周期(“热”)的一个例子:一种荷尔蒙诱发的生理状况,为人体成功交配做好准备(图\(\PageIndex{1}\) b)。 这些物种的雌性仅在周期的发情阶段交配。 在灵长类动物身上观察到的模式不同,包括人类和黑猩猩,尽管它们的月经周期使排卵期间每月可能只有几天怀孕,但它们在生育期的任何时候都可能尝试繁殖(图\(\PageIndex{1}\) c)。

Evolution Connection:果蝇中的能量预算、生殖成本和性选择

关于动物如何分配能量资源用于生长、维持和繁殖的研究使用了各种实验动物模型。 其中一些工作是使用常见的果蝇果蝇 melanogaster 完成的。 研究表明,就雄性果蝇的存活时间而言,繁殖不仅要付出代价,而且已经交配了好几次的果蝇剩余的繁殖精子也很有限。 果蝇通过选择最佳伴侣来最大限度地提高最后的繁殖机会。

在1981年的一项研究中,雄性果蝇与处女或受精雌性一起被安置在围栏中。 与处女雌性交配的雄性的寿命比与相同数量的受精雌性接触但无法交配的雄性的寿命短。 无论雄性有多大(表明他们的年龄),都会产生这种影响。 因此,没有交配的雄性寿命更长,这使他们将来有更多机会寻找伴侣。

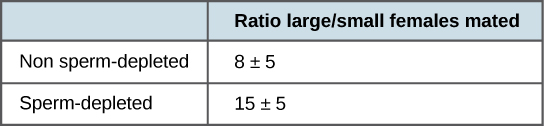

2006 年进行的最新研究表明,雄性如何选择与之交配的雌性,以及以前交配会对雌性有何影响(图\(\PageIndex{2}\)).1 Males were allowed to select between smaller and larger females. Findings showed that larger females had greater fecundity, producing twice as many offspring per mating as the smaller females did. Males that had previously mated, and thus had lower supplies of sperm, were termed “resource-depleted,” while males that had not mated were termed “non-resource-depleted.” The study showed that although non-resource-depleted males preferentially mated with larger females, this selection of partners was more pronounced in the resource-depleted males. Thus, males with depleted sperm supplies, which were limited in the number of times that they could mate before they replenished their sperm supply, selected larger, more fecund females, thus maximizing their chances for offspring. This study was one of the first to show that the physiological state of the male affected its mating behavior in a way that clearly maximizes its use of limited reproductive resources.

These studies demonstrate two ways in which the energy budget is a factor in reproduction. First, energy expended on mating may reduce an animal’s lifespan, but by this time they have already reproduced, so in the context of natural selection this early death is not of much evolutionary importance. Second, when resources such as sperm (and the energy needed to replenish it) are low, an organism’s behavior can change to give them the best chance of passing their genes on to the next generation. These changes in behavior, so important to evolution, are studied in a discipline known as behavioral biology, or ethology, at the interface between population biology and psychology.

Summary

All species have evolved a pattern of living, called a life history strategy, in which they partition energy for growth, maintenance, and reproduction. These patterns evolve through natural selection; they allow species to adapt to their environment to obtain the resources they need to successfully reproduce. There is an inverse relationship between fecundity and parental care. A species may reproduce early in life to ensure surviving to a reproductive age or reproduce later in life to become larger and healthier and better able to give parental care. A species may reproduce once (semelparity) or many times (iteroparity) in its life.

Footnotes

- 1 Adapted from Phillip G. Byrne and William R. Rice, “Evidence for adaptive male mate choice in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster,” Proc Biol Sci. 273, no. 1589 (2006): 917-922, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3372.

Glossary

- energy budget

- allocation of energy resources for body maintenance, reproduction, and parental care

- fecundity

- potential reproductive capacity of an individual

- iteroparity

- life history strategy characterized by multiple reproductive events during the lifetime of a species

- life history

- inherited pattern of resource allocation under the influence of natural selection and other evolutionary forces

- semelparity

- life history strategy characterized by a single reproductive event followed by death