8.2: 记忆如何运作

- Page ID

- 203415

学习目标

- 讨论记忆的三个基本功能

- 描述内存存储的三个阶段

- 描述和区分程序记忆和陈述性记忆以及语义和情景记忆

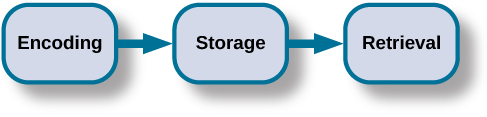

内存是一种信息处理系统;因此,我们经常将其与计算机进行比较。 内存是一组进程,用于在不同时间段内编码、存储和检索信息。

编码

我们通过一个叫做编码的过程将信息传入我们的大脑,这是将信息输入到存储系统中。 一旦我们收到来自环境的感官信息,我们的大脑就会对其进行标记或编码。 我们将信息与其他类似信息一起组织,并将新概念与现有概念联系起来。 编码信息是通过自动处理和费力处理进行的。

如果有人问你今天午餐吃了什么,你很可能很容易想起这些信息。 这被称为自动处理,即时间、空间、频率和单词含义等细节的编码。 自动处理通常是在没有任何意识的情况下完成的。 回想一下你上次学习考试的时候是自动处理的又一个例子。 但是你研究的实际测试材料呢? 要对这些信息进行编码,你可能需要大量的工作和注意力。 这被称为费力处理。

确保重要记忆被正确编码的最有效方法是什么? 即使是简单的句子在有意义时也更容易回忆(Anderson,1984)。 阅读以下句子(Bransford & McCarrell,1974 年),然后移开视线,从\(30\)三分向后数到零,然后尝试写下句子(不要回头看这个页面!)。

- 香味很酸,因为接缝分开了。

- 航行没有因为瓶子破碎而延迟。

- 大海捞针很重要,因为布被撕开了。

你做得怎么样? 就其本身而言,你写下的陈述很可能令人困惑且难以回忆。 现在,尝试使用以下提示再写一遍:风笛、船舶洗礼和跳伞运动员。 接下来从四\(40\)分向后倒数,然后自己检查一下,看看这次你对句子的回忆如何。 你可以看到,这些句子现在更令人难忘了,因为每个句子都是在上下文中放置的。 当你让材质变得有意义时,它的编码效果要好得多。

有三种类型的编码。 单词的编码及其含义被称为语义编码。 威廉·布斯菲尔德(William Bousfield)(1935年)在一项实验中首次证明了这一点,他要求人们记住单词。 这些\(60\)词实际上分为四类含义,尽管参与者不知道这一点,因为这些词是随机呈现的。 当他们被要求记住这些单词时,他们倾向于按类别回忆它们,这表明他们在学习单词时注意单词的含义。

视觉编码是图像的编码,声学编码是声音,尤其是单词的编码。 要了解视觉编码的工作原理,请仔细阅读以下单词列表:汽车、关卡、狗、真相、书、价值。 如果你稍后被要求回忆起这份清单中的单词,你认为你最有可能记得哪些单词? 你可能会更轻松地回忆起汽车、狗和书这两个词,而回忆等级、真相和价值这两个词会更困难。 这是为什么? 因为与单纯的文字相比,你可以更容易地回忆图像(心理画面)。 当你读到汽车、狗和书这个词时,你在脑海中创造了这些东西的图像。 这些是具体、高意象的单词。 另一方面,诸如等级、真理和价值之类的抽象词是低意象的词。 高图像词在视觉和语义上都经过编码(Paivio,1986 年),从而建立了更强的记忆力。

现在让我们把注意力转向声学编码。 你开着车,收音机里有一首你至少\(10\)几年没听过的歌,但你一起唱歌,回想起每个字。 在美国,孩子们经常通过歌曲学习字母,他们通过押韵学习每个月的天数:“三十天有九月、/四月、六月和十一月;/其余的都有三十一天,/保存二月,还有二十八天,/每跳二十九天年。” 由于采用了声学编码,这些课程很容易记住。 我们对单词发出的声音进行编码。 这就是为什么我们教给幼儿的大部分内容都是通过歌曲、押韵和节奏完成的原因之一。

你认为三种编码类型中哪一种能让你最好地记住口头信息? 几年前,心理学家弗格斯·克雷克和恩德尔·图尔文(1975)进行了一系列实验以找出答案。 向参与者提供了话语以及有关他们的问题。 这些问题要求参与者在三个级别之一上处理单词。 视觉处理问题包括向参与者询问字母的字体之类的问题。 声学处理问题向参与者询问了单词的发音或押韵,语义处理问题向参与者询问了单词的含义。 在向参与者展示单词和问题后,他们被赋予了意想不到的回忆或识别任务。

用语义编码的单词比那些通过视觉或声学编码的单词更容易记住。 与较浅的视觉或声学编码相比,语义编码涉及更深层次的处理。 Craik和Tulving得出结论,我们通过语义编码可以最好地处理口头信息,尤其是当我们应用所谓的自我引用效应时。 自我参考效应是指与个人相关性较低的材料相比,个人对与自己相关的信息有更好的记忆力(Rogers、Kuiper & Kirker,1977 年)。 当你尝试记住本章中的概念时,语义编码对你有好处吗?

Storage

Once the information has been encoded, we have to somehow have to retain it. Our brains take the encoded information and place it in storage. Storage is the creation of a permanent record of information.

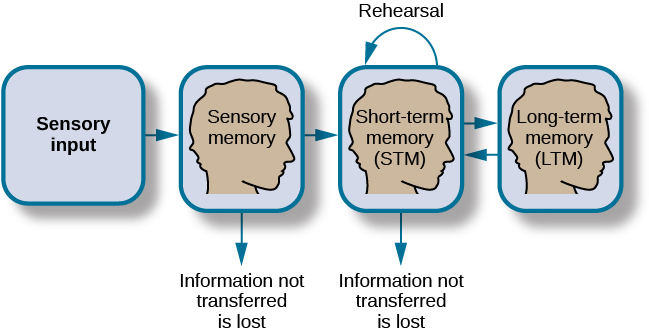

In order for a memory to go into storage (i.e., long-term memory), it has to pass through three distinct stages: Sensory Memory, Short-Term Memory, and finally Long-Term Memory. These stages were first proposed by Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin (1968). Their model of human memory, called Atkinson-Shiffrin (A-S), is based on the belief that we process memories in the same way that a computer processes information.

But A-S is just one model of memory. Others, such as Baddeley and Hitch (1974), have proposed a model where short-term memory itself has different forms. In this model, storing memories in short-term memory is like opening different files on a computer and adding information. The type of short-term memory (or computer file) depends on the type of information received. There are memories in visual-spatial form, as well as memories of spoken or written material, and they are stored in three short-term systems: a visuospatial sketchpad, an episodic buffer, and a phonological loop. According to Baddeley and Hitch, a central executive part of memory supervises or controls the flow of information to and from the three short-term systems.

Sensory Memory

In the Atkinson-Shiffrin model, stimuli from the environment are processed first in sensory memory: storage of brief sensory events, such as sights, sounds, and tastes. It is very brief storage—up to a couple of seconds. We are constantly bombarded with sensory information. We cannot absorb all of it, or even most of it. And most of it has no impact on our lives. For example, what was your professor wearing the last class period? As long as the professor was dressed appropriately, it does not really matter what she was wearing. Sensory information about sights, sounds, smells, and even textures, which we do not view as valuable information, we discard. If we view something as valuable, the information will move into our short-term memory system.

One study of sensory memory researched the significance of valuable information on short-term memory storage. J. R. Stroop discovered a memory phenomenon in the 1930s: you will name a color more easily if it appears printed in that color, which is called the Stroop effect. In other words, the word “red” will be named more quickly, regardless of the color the word appears in, than any word that is colored red. Try an experiment: name the colors of the words you are given in Figure. Do not read the words, but say the color the word is printed in. For example, upon seeing the word “yellow” in green print, you should say “green,” not “yellow.” This experiment is fun, but it’s not as easy as it seems.

Short-Term Memory

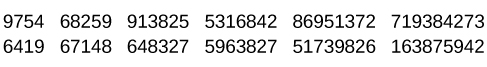

Short-term memory (STM) is a temporary storage system that processes incoming sensory memory; sometimes it is called working memory. Short-term memory takes information from sensory memory and sometimes connects that memory to something already in long-term memory. Short-term memory storage lasts about \(20\) seconds. George Miller (1956), in his research on the capacity of memory, found that most people can retain about \(7\) items in STM. Some remember \(5\), some \(9\), so he called the capacity of STM \(7\) plus or minus \(2\).

Think of short-term memory as the information you have displayed on your computer screen—a document, a spreadsheet, or a web page. Then, information in short-term memory goes to long-term memory (you save it to your hard drive), or it is discarded (you delete a document or close a web browser). This step of rehearsal, the conscious repetition of information to be remembered, to move STM into long-term memory is called memory consolidation.

You may find yourself asking, “How much information can our memory handle at once?” To explore the capacity and duration of your short-term memory, have a partner read the strings of random numbers out loud to you, beginning each string by saying, “Ready?” and ending each by saying, “Recall,” at which point you should try to write down the string of numbers from memory.

Note the longest string at which you got the series correct. For most people, this will be close to \(7\), Miller’s famous \(7\) plus or minus \(2\). Recall is somewhat better for random numbers than for random letters (Jacobs, 1887), and also often slightly better for information we hear (acoustic encoding) rather than see (visual encoding) (Anderson, 1969).

Long-term Memory

Long-term memory (LTM) is the continuous storage of information. Unlike short-term memory, the storage capacity of LTM has no limits. It encompasses all the things you can remember that happened more than just a few minutes ago to all of the things that you can remember that happened days, weeks, and years ago. In keeping with the computer analogy, the information in your LTM would be like the information you have saved on the hard drive. It isn’t there on your desktop (your short-term memory), but you can pull up this information when you want it, at least most of the time. Not all long-term memories are strong memories. Some memories can only be recalled through prompts. For example, you might easily recall a fact— “What is the capital of the United States?”—or a procedure—“How do you ride a bike?”—but you might struggle to recall the name of the restaurant you had dinner when you were on vacation in France last summer. A prompt, such as that the restaurant was named after its owner, who spoke to you about your shared interest in soccer, may help you recall the name of the restaurant.

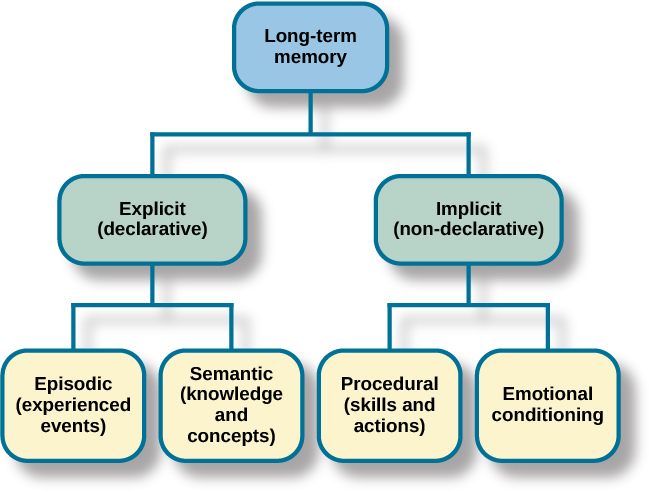

Long-term memory is divided into two types: explicit and implicit. Understanding the different types is important because a person’s age or particular types of brain trauma or disorders can leave certain types of LTM intact while having disastrous consequences for other types. Explicit memories are those we consciously try to remember and recall. For example, if you are studying for your chemistry exam, the material you are learning will be part of your explicit memory. (Note: Sometimes, but not always, the terms explicit memory and declarative memory are used interchangeably.)

Implicit memories are memories that are not part of our consciousness. They are memories formed from behaviors. Implicit memory is also called non-declarative memory.

Procedural memory is a type of implicit memory: it stores information about how to do things. It is the memory for skilled actions, such as how to brush your teeth, how to drive a car, how to swim the crawl (freestyle) stroke. If you are learning how to swim freestyle, you practice the stroke: how to move your arms, how to turn your head to alternate breathing from side to side, and how to kick your legs. You would practice this many times until you become good at it. Once you learn how to swim freestyle and your body knows how to move through the water, you will never forget how to swim freestyle, even if you do not swim for a couple of decades. Similarly, if you present an accomplished guitarist with a guitar, even if he has not played in a long time, he will still be able to play quite well.

Declarative memory has to do with the storage of facts and events we personally experienced. Explicit (declarative) memory has two parts: semantic memory and episodic memory. Semantic means having to do with language and knowledge about language. An example would be the question “what does argumentative mean?” Stored in our semantic memory is knowledge about words, concepts, and language-based knowledge and facts. For example, answers to the following questions are stored in your semantic memory:

- Who was the first President of the United States?

- What is democracy?

- What is the longest river in the world?

Episodic memory is information about events we have personally experienced. The concept of episodic memory was first proposed about \(40\) years ago (Tulving, 1972). Since then, Tulving and others have looked at scientific evidence and reformulated the theory. Currently, scientists believe that episodic memory is memory about happenings in particular places at particular times, the what, where, and when of an event (Tulving, 2002). It involves recollection of visual imagery as well as the feeling of familiarity (Hassabis & Maguire, 2007).

EVERYDAY CONNECTIONS: Can You Remember Everything You Ever Did or Said?

Episodic memories are also called autobiographical memories. Let’s quickly test your autobiographical memory. What were you wearing exactly five years ago today? What did you eat for lunch on April 10, 2009? You probably find it difficult, if not impossible, to answer these questions. Can you remember every event you have experienced over the course of your life—meals, conversations, clothing choices, weather conditions, and so on? Most likely none of us could even come close to answering these questions; however, American actress Marilu Henner, best known for the television show Taxi, can remember. She has an amazing and highly superior autobiographical memory.

Very few people can recall events in this way; right now, only \(12\) known individuals have this ability, and only a few have been studied (Parker, Cahill & McGaugh 2006). And although hyperthymesia normally appears in adolescence, two children in the United States appear to have memories from well before their tenth birthdays.

Retrieval

So you have worked hard to encode (via effortful processing) and store some important information for your upcoming final exam. How do you get that information back out of storage when you need it? The act of getting information out of memory storage and back into conscious awareness is known as retrieval. This would be similar to finding and opening a paper you had previously saved on your computer’s hard drive. Now it’s back on your desktop, and you can work with it again. Our ability to retrieve information from long-term memory is vital to our everyday functioning. You must be able to retrieve information from memory in order to do everything from knowing how to brush your hair and teeth, to driving to work, to knowing how to perform your job once you get there.

There are three ways you can retrieve information out of your long-term memory storage system: recall, recognition, and relearning. Recall is what we most often think about when we talk about memory retrieval: it means you can access information without cues. For example, you would use recall for an essay test. Recognition happens when you identify information that you have previously learned after encountering it again. It involves a process of comparison. When you take a multiple-choice test, you are relying on recognition to help you choose the correct answer. Here is another example. Let’s say you graduated from high school 10 years ago, and you have returned to your hometown for your 10-year reunion. You may not be able to recall all of your classmates, but you recognize many of them based on their yearbook photos.

The third form of retrieval is relearning, and it’s just what it sounds like. It involves learning information that you previously learned. Whitney took Spanish in high school, but after high school she did not have the opportunity to speak Spanish. Whitney is now 31, and her company has offered her an opportunity to work in their Mexico City office. In order to prepare herself, she enrolls in a Spanish course at the local community center. She’s surprised at how quickly she’s able to pick up the language after not speaking it for 13 years; this is an example of relearning.

Summary

Memory is a system or process that stores what we learn for future use.

Our memory has three basic functions: encoding, storing, and retrieving information. Encoding is the act of getting information into our memory system through automatic or effortful processing. Storage is retention of the information, and retrieval is the act of getting information out of storage and into conscious awareness through recall, recognition, and relearning. The idea that information is processed through three memory systems is called the Atkinson-Shiffrin (A-S) model of memory. First, environmental stimuli enter our sensory memory for a period of less than a second to a few seconds. Those stimuli that we notice and pay attention to then move into short-term memory (also called working memory). According to the A-S model, if we rehearse this information, then it moves into long-term memory for permanent storage. Other models like that of Baddeley and Hitch suggest there is more of a feedback loop between short-term memory and long-term memory. Long-term memory has a practically limitless storage capacity and is divided into implicit and explicit memory. Finally, retrieval is the act of getting memories out of storage and back into conscious awareness. This is done through recall, recognition, and relearning.

Glossary

- acoustic encoding

- input of sounds, words, and music

- Atkinson-Shiffrin model (A-S)

- memory model that states we process information through three systems: sensory memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory

- automatic processing

- encoding of informational details like time, space, frequency, and the meaning of words

- declarative memory

- type of long-term memory of facts and events we personally experience

- effortful processing

- encoding of information that takes effort and attention

- encoding

- input of information into the memory system

- episodic memory

- type of declarative memory that contains information about events we have personally experienced, also known as autobiographical memory

- explicit memory

- memories we consciously try to remember and recall

- implicit memory

- memories that are not part of our consciousness

- long-term memory (LTM)

- continuous storage of information

- memory

- system or process that stores what we learn for future use

- memory consolidation

- active rehearsal to move information from short-term memory into long-term memory

- procedural memory

- type of long-term memory for making skilled actions, such as how to brush your teeth, how to drive a car, and how to swim

- recall

- accessing information without cues

- recognition

- identifying previously learned information after encountering it again, usually in response to a cue

- rehearsal

- conscious repetition of information to be remembered

- relearning

- learning information that was previously learned

- retrieval

- act of getting information out of long-term memory storage and back into conscious awareness

- self-reference effect

- tendency for an individual to have better memory for information that relates to oneself in comparison to material that has less personal relevance

- semantic encoding

- input of words and their meaning

- semantic memory

- type of declarative memory about words, concepts, and language-based knowledge and facts

- sensory memory

- storage of brief sensory events, such as sights, sounds, and tastes

- short-term memory (STM)

- (also, working memory) holds about seven bits of information before it is forgotten or stored, as well as information that has been retrieved and is being used

- storage

- creation of a permanent record of information

- visual encoding

- input of images