9.3: Mfumo wa kuelezea harakati za kijamii

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 165312

- Dino Bozonelos, Julia Wendt, Charlotte Lee, Jessica Scarffe, Masahiro Omae, Josh Franco, Byran Martin, & Stefan Veldhuis

- Victor Valley College, Berkeley City College, Allan Hancock College, San Diego City College, Cuyamaca College, Houston Community College, and Long Beach City College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Malengo ya kujifunza

Mwishoni mwa sehemu hii, utaweza:

- Tathmini mfumo wa mambo kadhaa ambayo yanaelezea kuibuka na mafanikio ya harakati za kijamii

- Kutambua athari za mambo ya ziada kama vile mvuto wa kimataifa na mbinu zisizo na vurugu

Utangulizi

Harakati za kijamii mara nyingi huwa na matarajio makubwa ambayo hayawezi kufikiwa bila hatua ya pamoja. Karne ya ishirini na moja imeshuhudia kuongezeka kwa harakati nyingi za kijamii, kuanzia Movement Sunrise kukomesha mabadiliko ya hali ya hewa hadi harakati ya #metoo kwa ajili ya haki za wanawake na Black Lives Matter kwa haki za rangi. Harakati za kijamii za kihafidhina zimejumuisha Haki Mpya ya Kikristo na harakati mpya ya Haki duniani kote. Wakati sababu na washiriki hutofautiana sana, wasomi wamejaribu kutambua mambo ya kawaida katika harakati za kijamii na kuelezea hali ambayo harakati za kijamii zinaweza kutambua malengo yake.

Utafiti wa harakati za kijamii ni biashara ya kimataifa. Wanasayansi wa jamii wameleta zana za taaluma zao kubeba katika kuelewa kuibuka kwa ngumu ya uhamasishaji wa pamoja. Wanasaikolojia huleta mtazamo wao juu ya kiwango cha mtu binafsi cha uchambuzi, wakati wanasosholojia na wanasayansi wa kisiasa wanazingatia mienendo ya kikundi na mambo ya kitaasisi ambayo huwezesha au kuchochea harakati za kijamii. Mfumo mmoja wa kuelewa harakati za kijamii unazingatia mambo matatu kuu: fursa, shirika, na kutengeneza.

Uwezekano wa kisiasa

Mwandishi wa habari na mshairi wa Kifaransa Victor Hugo anahesabiwa kwa uchunguzi, “Hakuna kitu kilicho na nguvu kama wazo ambalo wakati umefika.” Wakati wa kutumia ufahamu huu wa matumaini kwa harakati za kijamii zinazotetea sababu, mambo ya mazingira. Wakati wa kuamka kwa mawazo inaweza kusababisha mabadiliko halisi tu wakati nyota fulani zinafanana. Wasomi wamegundua kwamba harakati za kijamii zina uwezekano mkubwa wa kuibuka na kushinda wakati muktadha mpana wa kisiasa unapokaribia mawazo yaliyokuzwa na harakati hiyo ya kijamii. Utetezi wa mabadiliko ya hali ya hewa ulipata kasi katika mitaa ya demokrasia tajiri wakati kulikuwa na majadiliano juu ya tatizo hili na wasomi wa kisiasa; harakati ya haki za mashoga ya Marekani ilipata kasi zaidi wakati maafisa waliochaguliwa walionyesha kuwa walikuwa tayari kubadili sera za sheria za muda mrefu dhidi ya ngono wachache.

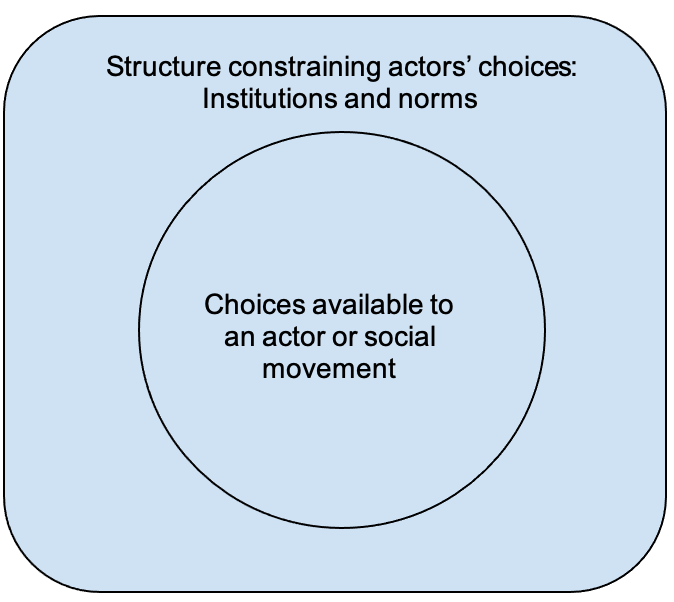

Nafasi ya kisiasa ni sababu ya kimuundo inayoathiri kama harakati za kijamii zinaunda na zinaweza kushinda katika malengo yake. Muundo hapa inahusu nguvu kubwa za kijamii katika kucheza wakati fulani: taasisi na kanuni, au imani na mazoea yaliyoshirikiwa sana, ambayo huzuia hatua ya mtu binafsi. Muundo unaweza kujumuisha kama taasisi za kisiasa na wasomi wanakubali mabadiliko maalum, kama jamii inakubali ujumbe na mbinu zinazokuzwa na harakati za kijamii. Kama David Meyer alivyopendekeza, kuna lazima iwe na “nafasi ya uvumilivu [katika] utawala” (2004, uk. 128) kwa wanaharakati kuhamasisha. Na jamii hiyo haipaswi kuwakandamiza wanaharakati kiasi kwamba hawana msamiati au njia za kutoa malalamiko yao. Muundo ni mazingira ambayo harakati za kijamii zinaweza kuunda na kushinikiza mabadiliko. Ndani ya muundo huu, wanaharakati wanaweza kuchagua kutoka mbinu mbalimbali kuhusu jinsi ya kuandaa, kuhamasisha, na sura malengo yao (Angalia Kielelezo hapa chini).

In the case of the US Civil Rights Movement that unfolded during the mid-twentieth century, markers of political opportunity can be identified in hindsight. These include the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling by the US Supreme Court, which declared unconstitutional the segregation of schools by race. Political leaders also signaled an opening, evident in public addresses such as President John F. Kennedy’s 1963 Report to the People on American Civil Rights, in which he declared, “It ought to be possible, in short, for every American to enjoy the privileges of being American without regard to his race or his color.” Such events signaled that powerful formal institutions were willing to change, and the time was ripe for a social movement to activate and accelerate that change.

Organization and mobilization

While the emergence of a political opening is key, a social moment cannot be sustained without strong organizational structures in place. As Lenin observed, a revolution will succeed when carried out by a vanguard party that offers an “organizational weapon” by which revolutionaries may strike down existing institutions. Successful communist party movements, such as those in Russia, China, and Cuba, relied on disciplined, hierarchical party organizations that reached down to cells of activists at the grassroots level.

More contemporary social movements need not have such extreme organization, but organizational strength is a direct correlate of mobilizational power and momentum. Douglas McAdam has studied several key organizations that facilitated the successes of the US Civil Rights Movement of the mid-twentieth century. These backbone organizations included Black churches, Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Black churches contained multigenerational communities united by bonds of faith and trust; HBCUs offered spaces for student organizing; the NAACP provided organizational and political resources to advance civil rights through mass protests, coordinated activities, and legal action. All of these organizations had proven capacity for carrying out complex community actions under adverse circumstances; they were also spaces for pooling resources and communicating initiatives to a relatively large audience of proven and potential activists (McAdam 1999).

Organizational forms may be more decentralized and less hierarchical by design. The “leaderless” Black Lives Matter movement in the US is an example of this: there is no singular set of charismatic leading figures such as Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, Huey P. Newton or Bobby Seale to set the tone and agenda. Local actions are organized and executed without direction from an organizational headquarters. One strength of this evolution in the organization of a social movement is more cellular organization, with new protest repertoires and messages emerging to suit local conditions and audiences. A disadvantage is the potential for the movement to lose momentum without clearly articulated and unifying goals.

New information and communication technologies (ICT) have changed the ways a social movement might organize and mobilize. By the dawn of the twenty-first century, there was optimism regarding the possibilities for uniting activists via social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter (Diamond and Plattner 2012). So-called “liberation technologies” were heralded as a means to organize a social movement in defiance of geographical constraints and even repressive governments. However, this initial optimism has been followed by critiques of these new technologies as leading to “armchair activism” by individuals unwilling to invest real resources into a social movement. Social media platforms have also proven unruly spaces for organizing due to the challenges of misinformation, government interference, and weak bonds of trust between participants. The impact of ICT on the emergence and success of a social movement has thus yielded mixed results.

Framing

Political opportunity, organization, and mobilizational capacity are complemented by the framing of an issue. Framing refers to the ways in which a social problem is defined by, presented to and resonates with members of a social movement and society more broadly. Framing is a key strategic move because the chosen frames must be culturally appropriate and meaningful.

The concept of frames explicitly brings a psychological and emotional element into our understanding of social movements: individuals join because of an affinity for the cause rather than merely out of rational self-interest (Goodwin, Jasper, and Polletta 2001). They must actively engage in “sense making” and determine for themselves, as well as fellow activists, their purpose and goals. Framing can incite emotions such as anger over a perceived injustice but also psychological safety in the belief that one is part of a larger community with shared beliefs.

Framing takes place at the inception of a social movement. It can sustain the movement and attract additional adherents from society. Framing is critical when we consider how the modern environmental movement in the US was galvanized by publications such as Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring, which offered an evocative and powerful vision (a lifeless natural landscape) for understanding ecological disaster through the concrete example of overuse of chemical pesticides. This book helped to frame the problem and invoke the shock, anger, and anxieties that are part of the modern environmental justice movement.

International influences

Many of the causes embraced by social movements span countries, regions and the globe. Given the advent of globalization since the end of the Cold War in 1991, seemingly faraway events may resonate with global audiences: deforestation in Indonesia sparks protests in European cities over unsustainable practices in the supply chains of furniture companies that source wood from Borneo. Environmental activists in Indonesia thus find common cause with counterparts in the Netherlands. Social movements may diffuse across borders, with activists sharing tactics, resources, and providing moral support to one another in their common cause. Diffusion is defined as the spread of an idea, movement, tactics, strategies, and other resources across international borders. One prominent example of international diffusion is the spread of liberal democracy around the globe in the decades spanning the 1990s to the 2000s.

International "democracy promotion" efforts are one driver of this worldwide increase in democracy since the 1990s, whereby international resources are directed toward pro-democracy domestic social movements. These have been led by wealthy democracies (such as those of North America, the Antipodes, the EU, and Japan) to strengthen younger democracies worldwide. Democracy promotion can include a wide range of activities such as government-supported grants to pro-democracy activists in other countries, nonprofit exchanges of information and expertise, and more horizontal exchanges of knowledge and resources between democracy activists worldwide. Pro-democracy movements in countries as varied as Ukraine and Nicaragua receive support from international donors and advisors.

The role of nonviolence

There are consequences to the tactics chosen by social movement leaders and participants. The range of tactics that a social movement may employ is vast, and social movements are constantly innovating and creating new repertoires based on changing contexts, cultural symbols, and new technologies. New strategies emerge with each social movement. Pro-democracy Hong Kong protesters, as part of their movement to secure democratic rights and autonomy within the People’s Republic of China’s “One Country, Two Systems” framework, created new forms of protest in 2019. One notable tactic was occupying terminals of Hong Kong International Airport. This served to disrupt the business of a global city reliant on the flow of businesspeople and tourists by air and draw global attention to their plight.

These protestors and others opted for nonviolent strategies of protest, a tradition which has deep roots in various faith traditions dating back millennia. More recently, social movement leaders ranging from Mohandas K. Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr., have made significant philosophical contributions and practical applications of nonviolence to movements for social change.

Empirical research comparing nonviolent and violent resistance campaigns has found that nonviolent campaigns are twice as successful as their violent counterparts (53 percent compared with 26 percent) (Stephan and Chenoweth 2008). Note that campaigns are defined by Stephan and Chenoweth as “major nonstate rebellions … [which include] a series of repetitive, durable, organized, and observable events directed at a certain target to achieve a goal,” (2008, p. 8).

The success of nonviolent social movements is attributed to various factors. It is due to higher public perceptions of the legitimacy of nonviolent movements as well as greater public sympathy for movements committed to principles of nonviolence. Nonviolent movements also constrain government responses, as suppressing a nonviolent movement with force can drive public support -- domestic and international -- even more toward the aims of the social movement.