1.2: Hesabu halisi - Muhimu wa Algebra

- Page ID

- 180825

- Kuainisha idadi halisi kama nambari ya asili, nzima, integer, ya busara, au isiyo na maana.

- Fanya mahesabu kwa kutumia utaratibu wa shughuli.

- Tumia mali zifuatazo za namba halisi: commutative, associative, distributive, inverse, na utambulisho.

- Tathmini maneno ya algebraic.

- Kurahisisha maneno ya aljebraic.

Mara nyingi husema kuwa hisabati ni lugha ya sayansi. Ikiwa hii ni kweli, basi lugha ya hisabati ni namba. Matumizi ya kwanza ya namba yalitokea\(100\) karne zilizopita katika Mashariki ya Kati kuhesabu, au kuandika vitu. Wakulima, wanyama, na wafanyabiashara walitumia ishara, mawe, au alama ili kuashiria kiasi kimoja - mganda wa nafaka, kichwa cha mifugo, au urefu wa kitambaa, kwa mfano. Kufanya hivyo kulifanya biashara iwezekanavyo, na kusababisha mawasiliano bora na kuenea kwa ustaarabu.

Miaka mitatu hadi nne iliyopita, Wamisri walianzisha sehemu ndogo. Waliwatumia kwanza kuonyesha maonyesho. Baadaye, walizitumia kuwakilisha kiasi wakati wingi uligawanywa katika sehemu sawa.

Lakini vipi kama hapakuwa na ng'ombe wa biashara au mazao yote ya nafaka yalipotea katika mafuriko? Mtu anawezaje kuonyesha kuwepo kwa kitu? Kutoka nyakati za mwanzo, watu walikuwa na mawazo ya “hali ya msingi” wakati wa kuhesabu na kutumia alama mbalimbali kuwakilisha hali hii null. Hata hivyo, haikuwa hadi karibu karne ya tano B.D. nchini India kwamba sifuri iliongezwa kwenye mfumo wa namba na kutumika kama namba katika mahesabu.

Wazi, pia kulikuwa na haja ya idadi kuwakilisha hasara au madeni. Nchini India, katika karne ya saba B.K., namba hasi zilitumika kama ufumbuzi wa equations hisabati na madeni ya kibiashara. Vipingamizi vya namba za kuhesabu vilipanua mfumo wa namba hata zaidi.

Kwa sababu ya mageuzi ya mfumo wa namba, sasa tunaweza kufanya mahesabu magumu kwa kutumia haya na makundi mengine ya namba halisi. Katika sehemu hii, sisi kuchunguza seti ya idadi, mahesabu na aina tofauti ya idadi, na matumizi ya idadi katika maneno.

Kuainisha Nambari halisi

Nambari tunayotumia kwa kuhesabu, au kuorodhesha vitu, ni namba za asili:\(1, 2, 3, 4, 5\) na kadhalika. Sisi kuelezea yao katika kuweka nukuu kama\(\{1,2,3,...\}\) ambapo ellipsis\((\cdots)\) inaonyesha kwamba idadi kuendelea infinity. Nambari za asili ni, bila shaka, pia huitwa namba za kuhesabu. Wakati wowote sisi enumerate wanachama wa timu, kuhesabu sarafu katika ukusanyaji, au Tally miti katika shamba, sisi ni kutumia seti ya idadi ya asili. Seti ya namba nzima ni seti ya namba za asili pamoja na sifuri:\(\{0,1,2,3,...\}\).

Seti ya integers inaongeza kinyume cha idadi ya asili kwa seti ya namba nzima:\(\{\cdots,-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3,\cdots\}\). Ni muhimu kutambua kwamba seti ya integers imeundwa na subsets tatu tofauti: integers hasi, sifuri, na integers chanya. Kwa maana hii, integers chanya ni idadi tu ya asili. Njia nyingine ya kufikiri juu yake ni kwamba idadi ya asili ni subset ya integers.

\[ \overbrace{\cdots, -3,-2,-1}^{\text{negative integers}}, \underbrace{0}_{\text{zero}}, \overbrace{1,\, 2,\,3,\, \cdots}^{\text{positive integers}} \nonumber\]

Seti ya namba za busara imeandikwa kama\(\{\frac{m}{n}| \text{m and n are integers and } n \neq 0\}\) .Angalia kutoka kwa ufafanuzi kwamba namba za busara ni sehemu ndogo (au quotients) zilizo na integers katika nambari zote mbili na denominator, na denominator haipo kamwe\(0\). Pia tunaweza kuona kwamba kila idadi ya asili, idadi nzima, na integer ni idadi ya busara na denominator ya\(1\).

Kwa sababu ni sehemu ndogo, nambari yoyote ya busara inaweza pia kuelezwa kwa fomu ya decimal. Nambari yoyote ya busara inaweza kuwakilishwa kama ama:

- decimal kukomesha:\(\frac{15}{8} =1.875\), au

- decimal kurudia:\(\frac{4}{11} =0.36363636\cdots = 0.\bar{36}\)

Tunatumia mstari uliotolewa juu ya kizuizi cha kurudia cha namba badala ya kuandika kikundi mara nyingi.

Andika kila moja ya yafuatayo kama namba ya busara. Andika sehemu na integer katika nambari na\(1\) in the denominator.

- \(7\)

- \(0\)

- \(-8\)

Suluhisho

a.\(7= \frac{7}{1}\)

b.\(0= \frac{0}{1}\)

c.\(-8= \frac{-8}{1}\)

Andika kila moja ya yafuatayo kama namba ya busara.

- \(11\)

- \(3\)

- \(-4\)

- Jibu

-

- \(\frac{11}{1}\)

- \(\frac{3}{1}\)

- \(-\frac{4}{1}\)

Andika kila moja ya namba zifuatazo za busara kama ama kukomesha au kurudia decimal.

- \(-\frac{5}{7}\)

- \(\frac{15}{5}\)

- \(\frac{13}{25}\)

Suluhisho

a. decimal kurudia

b.\(\frac{15}{5} = 3\) (au\(3.0\)), decimal kukomesha

c.\(\frac{13}{25} =0.52\), decimal ya kukomesha

Andika kila moja ya namba zifuatazo za busara kama ama kukomesha au kurudia decimal.

- \(\frac{68}{17}\)

- \(\frac{8}{13}\)

- \(-\frac{13}{25}\)

- Jibu

-

- \(4\)(au\(4.0\)), kukomesha

- \(0.\overline{615384}\), kurudia

- \(-0.85\), kukomesha

Idadi irrational

Wakati fulani katika zamani za zamani, mtu aligundua kuwa sio namba zote ni namba za busara. Wajenzi, kwa mfano, wanaweza kuwa wamegundua kwamba uwiano wa mraba na pande za kitengo haukuwa\(2\) au hata\(32\), lakini ilikuwa kitu kingine. Au mtengenezaji wa nguo anaweza kuwa aliona kwamba uwiano wa mduara kwa kipenyo cha kitambaa ilikuwa kidogo zaidi kuliko\(3\), lakini bado si namba ya busara. Nambari hizo zinasemekana kuwa zisizo na maana kwa sababu haziwezi kuandikwa kama sehemu ndogo. Nambari hizi hufanya seti ya namba zisizo na maana. Nambari zisizofaa haziwezi kuonyeshwa kama sehemu ya integers mbili. Haiwezekani kuelezea seti hii ya namba kwa utawala mmoja isipokuwa kusema kwamba namba haina maana ikiwa si ya busara. Kwa hiyo tunaandika hii kama inavyoonekana.

\[\{h\mid h \text { is not a rational number}\}\]

Kuamua kama kila moja ya namba zifuatazo ni ya busara au isiyo ya maana. Ikiwa ni busara, onyesha ikiwa ni kukomesha au kurudia decimal.

- \(\sqrt{25}\)

- \(\frac{33}{9}\)

- \(\sqrt{11}\)

- \(\frac{17}{34}\)

- \(0.3033033303333…\)

Suluhisho

- \(\sqrt{25}\): Hii inaweza kuwa rahisi\(\sqrt{25} = 5\) kama.Kwa hiyo,\(\sqrt{25}\) ni busara.

- \(\frac{33}{9}\): Kwa sababu ni sehemu,\(\frac{33}{9}\) ni idadi ya busara. Kisha, kurahisisha na ugawanye. \[\frac{33}{9}=\cancel{\frac{33}{9}} \nonumber\]Hivyo,\(\frac{33}{9}\) ni busara na decimal kurudia.

- \(\sqrt{11}\): Hii haiwezi kuwa rahisi zaidi. Kwa hiyo,\(\sqrt{11}\) ni idadi irrational.

- \(\frac{17}{34}\): Kwa sababu ni sehemu,\(\frac{17}{34}\) ni idadi ya busara. Rahisisha na ugawanye. \[\frac{17}{34} = 0.5 \nonumber\]Hivyo,\(\frac{17}{34}\) ni busara na decimal kukomesha.

- \(0.3033033303333…\)si decimal kukomesha. Pia kumbuka kuwa hakuna mfano wa kurudia kwa sababu kundi la\(3s\) ongezeko kila wakati. Kwa hiyo sio kukomesha wala decimal ya kurudia na, kwa hiyo, si namba ya busara. Ni idadi irrational.

Kuamua kama kila moja ya namba zifuatazo ni ya busara au isiyo ya maana. Ikiwa ni busara, onyesha ikiwa ni kukomesha au kurudia decimal.

- \(\frac{7}{77}\)

- \(\sqrt{81}\)

- \(4.27027002700027…\)

- \(\frac{91}{13}\)

- \(\sqrt{39}\)

- Jibu

-

- busara na kurudia;

- busara na kukomesha;

- isiyo ya maana;

- busara na kukomesha;

- isiyo na maana

Hesabu halisi

Kutokana na idadi yoyote\(n\), tunajua kwamba\(n\) ni ama busara au irrational. Haiwezi kuwa wote wawili. Seti ya namba za busara na zisizo na maana pamoja hufanya seti ya namba halisi. Kama tulivyoona na integers, nambari halisi zinaweza kugawanywa katika subsets tatu: namba halisi hasi, sifuri, na namba halisi halisi. Kila subset inajumuisha sehemu ndogo, decimals, na namba zisizo na maana kulingana na ishara yao ya algebraic (+ au -). Zero inachukuliwa kuwa si chanya wala hasi.

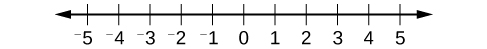

Nambari halisi inaweza kutazamwa kwenye mstari wa namba ya usawa na hatua ya kiholela iliyochaguliwa kama\(0\), na namba hasi upande wa kushoto wa\(0\) na namba nzuri kwa haki ya\(0\). fasta kitengo umbali ni kisha kutumika kwa alama off kila integer (au thamani nyingine ya msingi) upande wowote wa\(0\). Nambari yoyote halisi inalingana na nafasi ya pekee kwenye mstari wa nambari. Kuzungumza pia ni kweli: Kila eneo kwenye mstari wa nambari inalingana na nambari moja halisi. Hii inajulikana kama mawasiliano ya moja kwa moja. Sisi rejea hii kama mstari halisi idadi kama inavyoonekana katika Kielelezo (\(\PageIndex{1}\).

Kuainisha kila idadi kama ama chanya au hasi na kama ama busara au irrational. Je, idadi uongo upande wa kushoto au haki ya\(0\) juu ya mstari namba?

- \(-\frac{10}{3}\)

- \(-\sqrt{5}\)

- \(-6π\)

- \(0.615384615384…\)

Suluhisho

- \(-\frac{10}{3}\)ni hasi na busara. Ni uongo upande wa kushoto wa\(0\) kwenye mstari namba.

- \(-\sqrt{5}\)ni chanya na irrational. Ni uongo na haki ya\(0\).

- \(-\sqrt{289} = -\sqrt{17^2} = -17\)ni hasi na busara. Ni uongo upande wa kushoto wa\(0\).

- \(-6π\)ni hasi na irrational. Ni uongo upande wa kushoto wa\(0\).

- \(0.615384615384…\)ni decimal kurudia hivyo ni busara na chanya. Ni uongo na haki ya\(0\).

Kuainisha kila idadi kama ama chanya au hasi na kama ama busara au irrational. Je, idadi uongo upande wa kushoto au haki ya\(0\) juu ya mstari namba?

- \(\sqrt{73}\)

- \(-11.411411411…\)

- \(\frac{47}{19}\)

- \(-\frac{\sqrt{5}}{2}\)

- \(6.210735\)

- Jibu

-

- chanya, irrational

- haki hasi, busara

- kushoto chanya, busara

- haki - hasi, isiyo ya maana

- kushoto chanya, busara; haki

Seti ya Hesabu kama Subsets

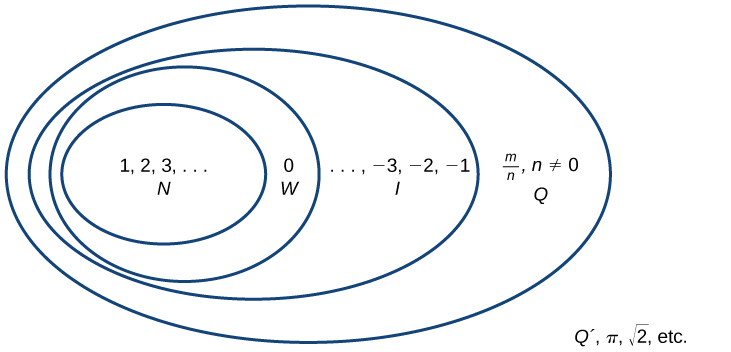

Kuanzia na idadi ya asili, tumepanua kila seti ili kuunda seti kubwa, maana yake ni kwamba kuna uhusiano wa subset kati ya seti ya namba tumekutana hadi sasa. Mahusiano haya yanaonekana wazi zaidi wakati unaonekana kama mchoro, kama Mchoro (\(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Seti ya namba asilia ni pamoja na namba zinazotumiwa kuhesabu:\(\{1,2,3,...\}\).

Seti ya namba nzima ni seti ya namba za asili pamoja na sifuri:\(\{0,1,2,3,...\}\).

Seti ya integers inaongeza idadi hasi ya asili kwa seti ya namba nzima:\(\{...,-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3,...\}\).

Seti ya namba za busara ni pamoja na sehemu ndogo zilizoandikwa kama\(\{\frac{m}{n} | \text{m and n are integers and } n \neq 0\}\).

Seti ya namba zisizo na maana ni seti ya namba ambazo si za busara, hazipatikani, na hazipatikani:\(\{h\parallel \text{h is not a rational number}\}\).

Weka kila nambari kama namba ya asili (N), namba nzima (W), integer (I), nambari ya busara (Q), na/au namba isiyo na maana (Q).

- \(\sqrt{36}\)

- \(\frac{8}{3}\)

- \(\sqrt{73}\)

- \(-6\)

- \(3.2121121112…\)

Suluhisho

| N | W | I | Q | Q' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a.\(\sqrt{36} = 6\) | X | X | X | X | |

| b.\(\frac{8}{3} =2.\overline{6}\) | X | ||||

| c.\(\sqrt{73}\) | X | ||||

| d.\(-6\) | X | X | |||

| e.\(3.2121121112...\) | X |

Weka kila nambari kama namba ya asili (N), namba nzima (W), integer (I), nambari ya busara (Q), na/au namba isiyo na maana (Q).

- \(-\frac{35}{7}\)

- \(0\)

- \(\sqrt{169}\)

- \(\sqrt{24}\)

- \(4.763763763...\)

- Jibu

-

N W I Q Q' a.\(-\frac{35}{7}\) X X b.\(0\) X X X c.\(\sqrt{169}\) X X X X d.\(\sqrt{24}\) X e.\(4.763763763...\) X

Kufanya Mahesabu Kutumia Utaratibu wa Uendeshaji

Wakati sisi kuzidisha idadi peke yake, sisi mraba au kuongeza kwa nguvu ya\(2\). Kwa mfano,\(4^2 =4\times4=16\). Tunaweza kuongeza idadi yoyote kwa nguvu yoyote. Kwa ujumla, nukuu ya kielelezo ina maana kwamba idadi au kutofautiana\(a\) hutumiwa kama\(n\) mara ya sababu.

\[a^n=a\cdot a\cdot a\cdots a \qquad \text{ n factors} \nonumber \]

Katika nukuu hii,\(a^n\) ni kusoma kama\(n^{th}\) nguvu ya\(a\), ambapo\(a\) inaitwa msingi na\(n\) inaitwa exponent. Neno katika nukuu ya kielelezo inaweza kuwa sehemu ya kujieleza hisabati, ambayo ni mchanganyiko wa idadi na shughuli. Kwa mfano,\(24+6 \times \dfrac{2}{3} − 4^2\) ni usemi wa hisabati.

Ili kutathmini kujieleza hisabati, tunafanya shughuli mbalimbali. Hata hivyo, hatuwezi kuifanya kwa utaratibu wowote wa random. Tunatumia utaratibu wa shughuli. Hii ni mlolongo wa sheria za kutathmini maneno hayo.

Kumbuka kwamba katika hisabati tunatumia mabano (), mabano [], na braces {} kwa namba za kikundi na maneno ili kitu chochote kinachoonekana ndani ya alama kinatibiwa kama kitengo. Zaidi ya hayo, baa za sehemu, radicals, na baa za thamani kamili zinatibiwa kama alama za makundi. Wakati wa kutathmini usemi wa hisabati, kuanza kwa kurahisisha maneno ndani ya alama za kikundi.

Hatua inayofuata ni kushughulikia maonyesho yoyote au radicals. Baadaye, fanya kuzidisha na mgawanyiko kutoka kushoto kwenda kulia na hatimaye kuongeza na kuondoa kutoka kushoto kwenda kulia.

Hebu tuangalie maneno yaliyotolewa.

\[24+6 \times \dfrac{2}{3} − 4^2 \nonumber\]

Hakuna alama kambi, hivyo sisi kuendelea na exponents au radicals. Idadi\(4\) hufufuliwa kwa nguvu ya\(2\), hivyo kurahisisha\(4^2\) kama\(16\).

\[24+6 \times \dfrac{2}{3} − 4^2 \nonumber \]

\[24+6 \times \dfrac{2}{3} − 16 \nonumber\]

Kisha, fanya kuzidisha au mgawanyiko, kushoto kwenda kulia.

\[24+6 \times \dfrac{2}{3} − 16 \nonumber\]

\[24+4-16 \nonumber\]

Mwishowe, fanya kuongeza au uondoe, kushoto kwenda kulia.

\[24+4−16 \nonumber\]

\[28−16 \nonumber\]

\[12 \nonumber\]

Kwa hiyo,

\[24+6 \times \dfrac{2}{3} − 4^2 =12 \nonumber\]

Kwa maneno mengine ngumu, hupita kadhaa kupitia utaratibu wa shughuli zitahitajika. Kwa mfano, kunaweza kuwa na usemi mkali ndani ya mabano ambayo lazima iwe rahisi kabla ya mabano yanatathminiwa. Kufuatia utaratibu wa shughuli kuhakikisha kwamba mtu yeyote kurahisisha huo hisabati kujieleza kupata matokeo sawa.

Uendeshaji katika maneno ya hisabati lazima tathmini katika utaratibu wa utaratibu, ambayo inaweza kuwa rahisi kwa kutumia kifupi PEMDAS:

- P (arentheses)

- E (vipengele)

- M (kuzidisha) na D (mgawanyiko)

- A (kuongeza) na S (uondoaji)

- Kurahisisha maneno yoyote ndani ya alama za kikundi.

- Kurahisisha maneno yoyote zenye exponents au radicals.

- Fanya kuzidisha na mgawanyiko wowote kwa utaratibu, kutoka kushoto kwenda kulia.

- Fanya kuongeza na uondoe kwa utaratibu, kutoka kushoto kwenda kulia.

Tumia utaratibu wa shughuli ili kutathmini kila moja ya maneno yafuatayo.

- \(\dfrac{5^2-4}{7}- \sqrt{11-2}\)

- \(\dfrac{14-3 \times2}{2 \times5-3^2}\)

- \(7\times(5\times3)−2\times[(6−3)−4^2]+1\)

Suluhisho

- \[\begin{align*} (3\times2)^2-4\times(6+2)&=(6)^2-4\times(8) && \qquad \text{Simplify parentheses}\\ &=36-4\times8 && \qquad \text{Simplify exponent}\\ &=36-32 && \qquad \text{Simplify multiplication}\\ &=4 && \qquad \text{Simplify subtraction}\\ \end{align*}\]

- \[\begin{align*} \dfrac{5^2-4}{7}- \sqrt{11-2}&= \dfrac{5^2-4}{7}-\sqrt{9} && \qquad \text{Simplify grouping symbols (radical)}\\ &=\dfrac{5^2-4}{7}-3 && \qquad \text{Simplify radical}\\ &=\dfrac{25-4}{7}-3 && \qquad \text{Simplify exponent}\\ &=\dfrac{21}{7}-3 && \qquad \text{Simplify subtraction in numerator}\\ &=3-3 && \qquad \text{Simplify division}\\ &=0 && \qquad \text{Simplify subtraction} \end{align*}\]

Kumbuka kuwa katika hatua ya kwanza, radical ni kutibiwa kama ishara ya kikundi, kama mabano. Pia, katika hatua ya tatu, bar ya sehemu inachukuliwa kuwa ishara ya kikundi hivyo namba inachukuliwa kuwa kikundi.

- \[\begin{align*} 6-\mid 5-8\mid +3\times(4-1)&=6-|-3|+3\times3 && \qquad \text{Simplify inside grouping symbols}\\ &=6-3+3\times3 && \qquad \text{Simplify absolute value}\\ &=6-3+9 && \qquad \text{Simplify multiplication}\\ &=3+9 && \qquad \text{Simplify subtraction}\\ &=12 && \qquad \text{Simplify addition}\\ \end{align*}\]

- \[\begin{align*} \dfrac{14-3 \times2}{2 \times5-3^2}&=\dfrac{14-3 \times2}{2 \times5-9} && \qquad \text{Simplify exponent}\\ &=\dfrac{14-6}{10-9} && \qquad \text{Simplify products}\\ &=\dfrac{8}{1} && \qquad \text{Simplify differences}\\ &=8 && \qquad \text{Simplify quotient}\\ \end{align*}\]

Katika mfano huu, bar ya sehemu hutenganisha nambari na denominator, ambayo tunapunguza tofauti hadi hatua ya mwisho.

- \[\begin{align*} 7\times(5\times3)-2\times[(6-3)-4^2]+1&=7\times(15)-2\times[(3)-4^2]+1 && \qquad \text{Simplify inside parentheses}\\ &=7\times(15)-2\times(3-16)+1 && \qquad \text{Simplify exponent}\\ &=7\times(15)-2\times(-13)+1 && \qquad \text{Subtract}\\ &=105+26+1 && \qquad \text{Multiply}\\ &=132 && \qquad \text{Add} \end{align*}\]

Tumia utaratibu wa shughuli ili kutathmini kila moja ya maneno yafuatayo.

- \(\sqrt{5^2-4^2}+7\times(5-4)^2\)

- \(1+\dfrac{7\times5-8\times4}{9-6}\)

- \(|1.8-4.3|+0.4\times\sqrt{15+10}\)

- \(\dfrac{1}{2}\times[5\times3^2-7^2]+\dfrac{1}{3}\times9^2\)

- \([(3-8^2)-4]-(3-8)\)

- Jibu

-

- \(10\)

- \(2\)

- \(4.5\)

- \(25\)

- \(26\)

Kutumia Mali ya Hesabu halisi

Kwa shughuli zingine tunazofanya, utaratibu wa shughuli fulani haijalishi, lakini utaratibu wa shughuli nyingine hufanya. Kwa mfano, haina tofauti ikiwa tunavaa kiatu sahihi kabla ya kushoto au kinyume chake. Hata hivyo, haijalishi kama tunavaa viatu au soksi kwanza. Kitu kimoja ni kweli kwa shughuli katika hisabati.

Mali ya Kubadili

Mali ya kubadilisha ya kuongeza inasema kwamba namba zinaweza kuongezwa kwa utaratibu wowote bila kuathiri jumla.

\[a+b=b+a\]

Tunaweza kuona vizuri uhusiano huu wakati wa kutumia namba halisi.

\((−2)+7 = 5 \text{ and } 7+(−2)=5\)

Vile vile, mali ya kubadilisha ya kuzidisha inasema kwamba namba zinaweza kuongezeka kwa utaratibu wowote bila kuathiri bidhaa.

\[a\times b=b\times a\]

Tena, fikiria mfano na namba halisi.

Ni muhimu kutambua kwamba hakuna kuondoa wala mgawanyiko ni kubadilisha. Kwa mfano,\(17−5\) si sawa na\(5−17\). Vile vile,\(20÷5≠5÷20\).

Associative Mali

Mali ya ushirika wa kuzidisha inatuambia kwamba haijalishi jinsi tunavyokusanya namba wakati wa kuzidisha. Tunaweza kusonga alama za kikundi ili kufanya hesabu iwe rahisi, na bidhaa inabakia sawa.

\[a(bc)=(ab)c\]

Fikiria mfano huu.

\((3\times4)\times5=60 \text{ and } 3\times(4\times5)=60\)

Mali ya ushirika wa kuongeza inatuambia kwamba namba zinaweza kuunganishwa tofauti bila kuathiri jumla.

\[a+(b+c)=(a+b)+c\]

Mali hii inaweza kusaidia hasa wakati wa kushughulika na integers hasi. Fikiria mfano huu.

\([15+(−9)]+23=29 \text{ and } 15+[(−9)+23]=29\)

Je, ni uondoaji na mgawanyiko wa ushirika? Tathmini mifano hii.

\[\begin{align*} 8-(3-15)\overset{?}{=}&(8-3)-15\\ 8-(-12)\overset{?}{=}&5-15\\ 20 \neq &10\\ 64\div (8\div 4)\overset{?}{=}&(64\div 8)\div 4\\ 64\div 2\overset{?}{=}&8\div 4\\ 32 \neq & 2 \end{align*}\]

Kama tunaweza kuona, wala kuondoa wala mgawanyiko ni associative.

Mali ya Kusambaza

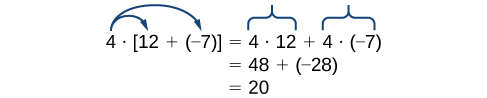

Mali ya usambazaji inasema kwamba bidhaa ya sababu mara jumla ni jumla ya mara sababu kila neno kwa jumla.

\[a\times(b+c)=a\times b+a\times c\]

Mali hii inachanganya wote kuongeza na kuzidisha (na ni mali tu ya kufanya hivyo). Hebu fikiria mfano.

Kumbuka kwamba\(4\) is outside the grouping symbols, so we distribute the \(4\) by multiplying it by \(12\), multiplying it by \(–7\), and adding the products.

To be more precise when describing this property, we say that multiplication distributes over addition. The reverse is not true, as we can see in this example.

\[\begin{align*} 6+(3\times5)\overset{?}{=}&(6+3)\times(6\times5)\\ 6+(15)\overset{?}{=}&(9)\times(11)\\ 21 \neq &99 \end{align*}\]

Multiplication does not distribute over subtraction, and division distributes over neither addition nor subtraction.

A special case of the distributive property occurs when a sum of terms is subtracted.

\[a−b=a+(−b)\]

For example, consider the difference \(12−(5+3)\). We can rewrite the difference of the two terms \(12\) and \((5+3)\) by turning the subtraction expression into addition of the opposite. So instead of subtracting \( (5+3)\), we add the opposite.

Now, distribute \(-1\) and simplify the result.

\[\begin{align*} 12-(5+3)&=12+(-1)\times(5+3)\\ &=12+[(-1)\times5+(-1)\times3]\\ &=12+(-8)\\ &=4 \end{align*}\]

This seems like a lot of trouble for a simple sum, but it illustrates a powerful result that will be useful once we introduce algebraic terms. To subtract a sum of terms, change the sign of each term and add the results. With this in mind, we can rewrite the last example.

\[\begin{align*} 12-(5+3)&=12+(-5-3)\\ &=12-8\\ &=4 \end{align*}\]

Identity Properties

The identity property of addition states that there is a unique number, called the additive identity \((0)\) that, when added to a number, results in the original number.

\[a+0=a\]

The identity property of multiplication states that there is a unique number, called the multiplicative identity \((1)\) that, when multiplied by a number, results in the original number.

\[a\times 1=a\]

For example, we have \( (−6)+0=−6\) and\( 23\times1=23\). There are no exceptions for these properties; they work for every real number, including \(0\) and \(1\).

Inverse Properties

The inverse property of addition states that, for every real number a, there is a unique number, called the additive inverse (or opposite), denoted \(−a\), that, when added to the original number, results in the additive identity, \(0\).

\[a+(−a)=0\]

For example, if \(a =−8\), the additive inverse is \(8\), since \((−8)+8=0\).

The inverse property of multiplication holds for all real numbers except \(0\) because the reciprocal of \(0\) is not defined. The property states that, for every real number \(a\), there is a unique number, called the multiplicative inverse (or reciprocal), denoted \(1a\), that, when multiplied by the original number, results in the multiplicative identity, \(1\).

\[a\times \dfrac{1}{a}=1\]

For example, if \(a =−\dfrac{2}{3}\), the reciprocal, denoted \(\dfrac{1}{a}\), is \(-\dfrac{3}{2}\) because

\[a⋅\dfrac{1}{a}=\left(−\dfrac{2}{3}\right)\times\left(−\dfrac{3}{2}\right)=1 \nonumber\]

The following properties hold for real numbers \(a\), \(b\), and \(c\).

| Addition | Multiplication | |

|---|---|---|

| Commutative Property | \(a+b=b+a\) | \(a\times b=b\times a\) |

| Associative Property | \(a+(b+c)=(a+b)+c\) | \(a(bc)=(ab)c\) |

| Distributive Property | \(a\times (b+c)=a\times b+a\times c\) | |

| Identity Property |

There exists a unique real number called the additive identity, 0, such that, for any real number a \(a+0=a\)

|

There exists a unique real number called the multiplicative identity, 1, such that, for any real number a \(a\times 1=a\)

|

| Inverse Property |

Every real number a has an additive inverse, or opposite, denoted –a, such that \(a+(−a)=0\)

|

Every nonzero real number a has a multiplicative inverse, or reciprocal, denoted 1a , such that \(a\times \left(\dfrac{1}{a}\right)=1\)

|

Use the properties of real numbers to rewrite and simplify each expression. State which properties apply.

- \(3\times 6+3\times 4\)

- \((5+8)+(−8)\)

- \(6−(15+9)\)

- \(\dfrac{4}{7}\times\left(\dfrac{2}{3}\times \dfrac{7}{4}\right)\)

- \(100\times[0.75+(−2.38)]\)

Solution

- \[\begin{align*} 3\times6+3\times4&=3\times(6+4)\qquad \text{Distributive property}\\ &=3\times10\qquad \text{Simplify}\\ &=30\qquad \text{Simplify}\\ \end{align*}\]

- \[\begin{align*} (5+8)+(-8)&=5+[8+(-8)]\qquad \text{Associative property of addition}\\ &=5+0\qquad \text{Inverse property of addition}\\ &=5\qquad \text{Identity property of addition}\\ \end{align*}\]

- \[\begin{align*} 6-(15+9)&=6+[(-15)+(-9)]\qquad \text{Distributive property}\\ &=6+(-24)\qquad \text{Simplify}\\ &=-18\qquad \text{Simplify}\\ \end{align*}\]

- \[\begin{align*} \dfrac{4}{7}\times\left(\dfrac{2}{3}\times\dfrac{7}{4}\right)&=\dfrac{4}{7}\times\left(\dfrac{7}{4}\times\dfrac{2}{3}\right)\qquad \text{Commutative property of multiplication}\\ &=\left(\dfrac{4}{7}\times\dfrac{7}{4}\right)\times\dfrac{2}{3}\qquad \text{Associative property of multiplication}\\ &=1\times\dfrac{2}{3}\qquad \text{Inverse property of multiplication}\\ &=\dfrac{2}{3}\qquad \text{Identity property of multiplication}\\ \end{align*}\]

- \[\begin{align*} 100\times[0.75+(-2.38)]&=100\times0.75+100\times(-2.38)\qquad \text{Distributive property}\\ &=75+(-238)\qquad \text{Simplify}\\ &=-163\qquad \text{Simplify} \end{align*}\]

Use the properties of real numbers to rewrite and simplify each expression. State which properties apply.

- \(\left(-\dfrac{23}{5}\right)\times\left[11\times\left(-\dfrac{5}{23}\right)\right]\)

- \(5\times(6.2+0.4)\)

- \(18-(7-15)\)

- \(\dfrac{17}{18}+\left[\dfrac{4}{9}+\left(-\dfrac{17}{18}\right)\right]\)

- \(6\times(-3)+6\times3\)

- Answer

-

- \(11)\), commutative property of multiplication

- \(33\), distributive property

- \(26\), distributive property

- \(\dfrac{4}{9}\), commutative property of addition, associative property of addition, inverse property of addition, identity property of addition

- \(0\), distributive property, inverse property of addition, identity property of addition

Evaluating Algebraic Expressions

So far, the mathematical expressions we have seen have involved real numbers only. In mathematics, we may see expressions such as \(x +5\), \(\dfrac{4}{3}\pi r^3\), or \(\sqrt{2m^3 n^2}\). In the expression \(x +5\), \(5\) is called a constant because it does not vary and \(x\) is called a variable because it does. (In naming the variable, ignore any exponents or radicals containing the variable.) An algebraic expression is a collection of constants and variables joined together by the algebraic operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division.

We have already seen some real number examples of exponential notation, a shorthand method of writing products of the same factor. When variables are used, the constants and variables are treated the same way.

\[\begin{align*} (-3)^5 &=(-3)\times(-3)\times(-3)\times(-3)\times(-3)\Rightarrow x^5=x\times x\times x\times x\times x\\ (2\times7)^3&=(2\times7)\times(2\times7)\times(2\times7)\qquad \; \; \Rightarrow (yz)^3=(yz)\times(yz)\times(yz) \end{align*}\]

In each case, the exponent tells us how many factors of the base to use, whether the base consists of constants or variables.

Any variable in an algebraic expression may take on or be assigned different values. When that happens, the value of the algebraic expression changes. To evaluate an algebraic expression means to determine the value of the expression for a given value of each variable in the expression. Replace each variable in the expression with the given value, then simplify the resulting expression using the order of operations. If the algebraic expression contains more than one variable, replace each variable with its assigned value and simplify the expression as before.

List the constants and variables for each algebraic expression.

- \(x + 5\)

- \(\dfrac{4}{3}\pi r^3\)

- \(\sqrt{2m^3 n^2}\)

Solution

| Constants | Variables | |

|---|---|---|

| a. \(x + 5\) | \(5\) | \(x\) |

| b. \(\dfrac{4}{3}\pi r^3\) | \(\dfrac{4}{3}\), \(\pi\) | \(r\) |

| c. \(\sqrt{2m^3 n^2}\) | \(2\) | \(m\),\(n\) |

List the constants and variables for each algebraic expression.

- \(2(L + W)\)

- \(4y^3+y\)

- Answer

-

Constants Variables a. \(2\pi r(r+h)\) \(2\),\(\pi\) \(r\),\(h\) b. \(2(L + W)\) \(2\) \(L\), \(W\) c. \(4y^3+y\) \(4\) \(y\)

Evaluate the expression \(2x−7\) for each value for \(x\).

- \(x=0\)

- \(x=1\)

- \(x=12\)

- \(x=−4\)

Solution

- Substitute \(0\) for \(x\). \[\begin{align*} 2x-7 &= 2(0)-7 \\ &= 0-7\\ &= -7\\ \end{align*}\]

- Substitute \(1\) for \(x\). \[\begin{align*} 2x-7 &= 2(1)-7 \\ &= 2-7\\ &= -5\\ \end{align*}\]

- Substitute \(\dfrac{1}{2}\) for \(x\). \[\begin{align*} 2x-7 &= 2\left (\dfrac{1}{2} \right )-7 \\ &= 1-7\\ &= -6\\ \end{align*}\]

- Substitute \(-4\) for \(x\). \[\begin{align*} 2x-7 &= 2(-4)-7 \\ &= -8-7\\ &= -15\\ \end{align*}\]

Evaluate the expression \(11−3y\) for each value for \(y\).

- \(y=2\)

- \(y=0\)

- \(y=\dfrac{2}{3}\)

- \(y=−5\)

- Answer

-

- \(11\)

- \(26\)

Evaluate each expression for the given values.

- \(x+5\) for \(x=-5\)

- \(\dfrac{t}{2t-1}\) for \(t=10\)

- \(\dfrac{4}{3}\pi r^3\) for \(r=5\)

- \(a+ab+b\) for \(a=11\), \(b=-8\)

- \(\sqrt{2m^3 n^2}\) for \(m=2\), \(n=3\)

Solution

- Substitute

\(-5\) for \(x\). \[\begin{align*} x+5 &= (-5)+5 \\ &= 0\\ \end{align*}\] - Substitute \(10\) for \(t\). \[\begin{align*} \dfrac{t}{2t-1} &= \dfrac{(10)}{2(10)-1} \\ &= \dfrac{10}{20-1}\\ &= \dfrac{10}{19}\\ \end{align*}\]

- Substitute \(5\) for \(r\)

. \[\begin{align*} \dfrac{4}{3} \pi r^3 &= \dfrac{4}{3}\pi (5)^3 \\ &= \dfrac{4}{3}\pi (125)\\ &= \dfrac{500}{3}\pi\\ \end{align*}\] - Substitute \(11\) for \(a\) and \(-8\) for \(b\)

. \[\begin{align*} a+ab+b &= (11)+(11)(-8)+(-8) \\ &= 11-88-8 \\ &= -85\\ \end{align*}\] - Substitute \(2\) for \(m\) and \(3\) for \(n\). \[\begin{align*} \sqrt{2m^3 n^2} &= \sqrt{2(2)^3 (3)^2} \\ &= \sqrt{2(8)(9)} \\ &= \sqrt{144} \\ &= 12 \end{align*}\]

Evaluate each expression for the given values.

- \(\dfrac{y+3}{y-3}\) for \(y=5\)

- \(7-2t\) for \(t=-2\)

- \(\dfrac{1}{3}\pi r^2\) for \(r=11\)

- \((p^2 q)^3\) for \(p=-2\), \(q=3\)

- \(4(m-n)-5(n-m)\) for \(m=\dfrac{2}{3}\) \(n=\dfrac{1}{3}\)

- Answer

-

- \(4\)

- \(11\)

- \(\dfrac{121}{3}\pi\)

- \(1728\)

- \(3\)

Formulas

An equation is a mathematical statement indicating that two expressions are equal. The expressions can be numerical or algebraic. The equation is not inherently true or false, but only a proposition. The values that make the equation true, the solutions, are found using the properties of real numbers and other results. For example, the equation \(2x +1= 7\) has the unique solution of \(3\) because when we substitute \(3\) for \(x\) in the equation, we obtain the true statement \(2(3)+1=7\).

A formula is an equation expressing a relationship between constant and variable quantities. Very often, the equation is a means of finding the value of one quantity (often a single variable) in terms of another or other quantities. One of the most common examples is the formula for finding the area \(A\) of a circle in terms of the radius \(r\) of the circle: \( A= \pi r^2\). For any value of \(r\), the area \(A\) can be found by evaluating the expression \(\pi r^2\).

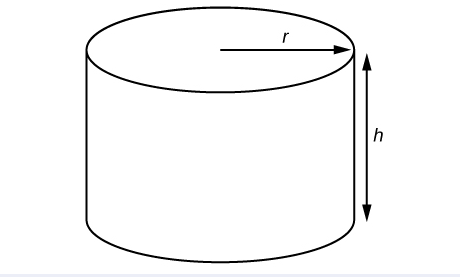

A right circular cylinder with radius \(r\) and height \(h\) has the surface area \(S\) (in square units) given by the formula \(S=2\pi r(r+h)\). See Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). Find the surface area of a cylinder with radius \(6\) in. and height \(9\) in. Leave the answer in terms of \(\pi\).

Evaluate the expression \(2\pi r(r+h)\) for \(r=6\) and \(h=9\).

Solution

\[\begin{align*} S &= 2\pi r(r+h) \\ &= 2\pi (6)[(6)+(9)] \\ &= 2\pi(6)(15) \\ &= 180\pi \end{align*}\]

The surface area is \(180\pi\) square inches.

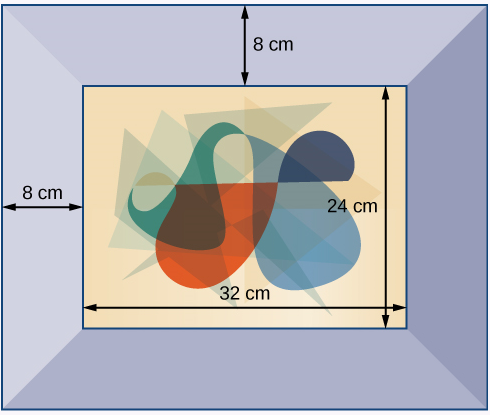

A photograph with length \(L\) and width \(W\) is placed in a matte of width \(8\) centimeters (cm). The area of the matte (in square centimeters, or \(cm^2\) is found to be \(A=(L+16)(W+16) - L\)⋅W

- Answer

-

\(1152cm^2\)

Simplifying Algebraic Expressions

Sometimes we can simplify an algebraic expression to make it easier to evaluate or to use in some other way. To do so, we use the properties of real numbers. We can use the same properties in formulas because they contain algebraic expressions.

Simplify each algebraic expression.

- \(3x-2y+x-3y-7\)

- \(2r-5(3-r)+4\)

- \(\left(4t-\dfrac{5}{4}s\right)-\left(\dfrac{2}{3}t+2s\right)\)

- \(2mn-5m+3mn+n\)

Solution

- \[\begin{align*} 3x-2y+x-3y-7&=3x+x-2y-3y-7 && \qquad \text{Commutative property of addition}\\ &=4x-5y-7 && \qquad \text{Simplify}\\ \end{align*}\]

- \[\begin{align*} 2r-5(3-r)+4&=2r-15+5r+4 && \qquad \qquad \qquad \text {Distributive property}\\ &=2r+5y-15+4 && \qquad \qquad \qquad \text{Commutative property of addition}\\ &=7r-11 && \qquad \qquad \qquad \text{Simplify}\\ \end{align*}\]

- \[\begin{align*} \left(4t-\dfrac{5}{4}s\right)-\left(\dfrac{2}{3}t+2s\right)&=4t-\dfrac{5}{4}s-\dfrac{2}{3}t-2s && \qquad \text{Distributive property}\\ &=4t-\dfrac{2}{3}t-\dfrac{5}{4}s-2s && \qquad \text{Commutative property of addition}\\ &=\dfrac{10}{3}t-\dfrac{13}{4}s && \qquad \text{Simplify}\\ \end{align*}\]

- \[\begin{align*} 2mn-5m+3mn+n&=2mn+3mn-5m+n && \qquad \text{Commutative property of addition}\\ &=5mn-5m+n && \qquad \text{Simplify}\\ \end{align*}\]

Simplify each algebraic expression.

- \(\dfrac{2}{3}y−2\left(\dfrac{4}{3}y+z\right)\)

- \(\dfrac{5}{t}−2−\dfrac{3}{t}+1\)

- \(4p(q−1)+q(1−p)\)

- \(9r−(s+2r)+(6−s)\)

- Answer

-

- \(−2y−2z\) or \(−2(y+z)\)

- \(\dfrac{2}{t}−1\)

- \(3pq−4p+q\)

- \(7r−2s+6\)

A rectangle with length \(L\) and width \(W\) has a perimeter \(P\) given by \(P =L+W+L+W\). Simplify this expression.

Solution

\[\begin{align*} P &=L+W+L+W\\ P &=L+L+W+W && \qquad \text{Commutative property of addition}\\ P &=2L+2W && \qquad \text{Simplify}\\ P &=2(L+W) && \qquad \text{Distributive property} \end{align*}\]

If the amount \(P\) is deposited into an account paying simple interest \(r\) for time \(t\), the total value of the deposit \(A\) is given by \(A =P+Prt\). Simplify the expression. (This formula will be explored in more detail later in the course.)

- Answer

-

\(A=P(1+rt)\)

Access these online resources for additional instruction and practice with real numbers.

Key Concepts

- Rational numbers may be written as fractions or terminating or repeating decimals. See Example and Example.

- Determine whether a number is rational or irrational by writing it as a decimal. See Example.

- The rational numbers and irrational numbers make up the set of real numbers. See Example. A number can be classified as natural, whole, integer, rational, or irrational. See Example.

- The order of operations is used to evaluate expressions. See Example.

- The real numbers under the operations of addition and multiplication obey basic rules, known as the properties of real numbers. These are the commutative properties, the associative properties, the distributive property, the identity properties, and the inverse properties. See Example.

- Algebraic expressions are composed of constants and variables that are combined using addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. See Example. They take on a numerical value when evaluated by replacing variables with constants. See Example,Example, and Example

- Formulas are equations in which one quantity is represented in terms of other quantities. They may be simplified or evaluated as any mathematical expression. See Example and Example.

Glossary

- algebraic expression

- constants and variables combined using addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division

- associative property of addition

- the sum of three numbers may be grouped differently without affecting the result; in symbols,a+(b+c)=(a+b)+c

- associative property of multiplication

- the product of three numbers may be grouped differently without affecting the result; in symbols,a⋅(b⋅c)=(a⋅b)⋅c

- base

- in exponential notation, the expression that is being multiplied

- commutative property of addition

- two numbers may be added in either order without affecting the result; in symbols,a+b=b+a

- commutative property of multiplication

- two numbers may be multiplied in any order without affecting the result; in symbols,a⋅b=b⋅a

- constant

- a quantity that does not change value

- distributive property

- the product of a factor times a sum is the sum of the factor times each term in the sum; in symbols,a⋅(b+c)=a⋅b+a⋅c

- equation

- a mathematical statement indicating that two expressions are equal

- exponent

- in exponential notation, the raised number or variable that indicates how many times the base is being multiplied

- exponential notation

- a shorthand method of writing products of the same factor

- formula

- an equation expressing a relationship between constant and variable quantities

- identity property of addition

- there is a unique number, called the additive identity, 0, which, when added to a number, results in the original number; in symbols,a+0=a

- identity property of multiplication

- there is a unique number, called the multiplicative identity, 1, which, when multiplied by a number, results in the original number; in symbols,a⋅1=a

- integers

- the set consisting of the natural numbers, their opposites, and 0:{…,−3,−2,−1,0,1,2,3,…}

- inverse property of addition

- for every real numbera,there is a unique number, called the additive inverse (or opposite), denoted−a,which, when added to the original number, results in the additive identity, 0; in symbols,a+(−a)=0

- inverse property of multiplication

- for every non-zero real numbera,there is a unique number, called the multiplicative inverse (or reciprocal), denoted1a,which, when multiplied by the original number, results in the multiplicative identity, 1; in symbols,a⋅1a=1

- irrational numbers

- the set of all numbers that are not rational; they cannot be written as either a terminating or repeating decimal; they cannot be expressed as a fraction of two integers

- natural numbers

- the set of counting numbers:{1,2,3,…}

- order of operations

- a set of rules governing how mathematical expressions are to be evaluated, assigning priorities to operations

- rational numbers

- the set of all numbers of the formmn,wheremandnare integers andn≠0.Any rational number may be written as a fraction or a terminating or repeating decimal.

- real number line

- a horizontal line used to represent the real numbers. An arbitrary fixed point is chosen to represent 0; positive numbers lie to the right of 0 and negative numbers to the left.

- real numbers

- the sets of rational numbers and irrational numbers taken together

- variable

- a quantity that may change value

- whole numbers

- the set consisting of 0 plus the natural numbers:{0,1,2,3,…}