8.2: Jinsi Kumbukumbu Kazi

- Page ID

- 177448

Malengo ya kujifunza

- Jadili kazi tatu za msingi za kumbukumbu

- Eleza hatua tatu za hifadhi ya kumbukumbu

- Eleza na kutofautisha kati ya kumbukumbu ya utaratibu na ya kutangaza na kumbukumbu ya semantic na episodic

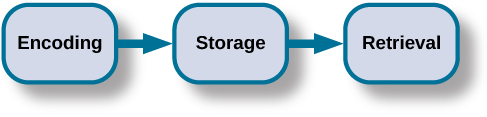

Kumbukumbu ni mfumo wa usindikaji wa habari; kwa hiyo, mara nyingi tunalinganisha na kompyuta. Kumbukumbu ni seti ya michakato inayotumiwa kwa encode, kuhifadhi, na kurejesha habari juu ya vipindi tofauti vya muda.

Usimbaji

Tunapata habari ndani ya akili zetu kupitia mchakato unaoitwa encoding, ambayo ni pembejeo ya habari katika mfumo wa kumbukumbu. Mara tu tunapopokea maelezo ya hisia kutoka kwa mazingira, akili zetu zinaandika au kuziandika. Tunaandaa habari na maelezo mengine yanayofanana na kuunganisha dhana mpya kwa dhana zilizopo. Maelezo ya encoding hutokea kwa njia ya usindikaji wa moja kwa moja na usindikaji

Ikiwa mtu anakuuliza kile ulichokula chakula cha mchana leo, zaidi ya uwezekano unaweza kukumbuka habari hii kwa urahisi kabisa. Hii inajulikana kama usindikaji wa moja kwa moja, au encoding ya maelezo kama wakati, nafasi, mzunguko, na maana ya maneno. Usindikaji wa moja kwa moja hufanyika bila ufahamu wowote. Kukumbuka mara ya mwisho uliyojifunza kwa mtihani ni mfano mwingine wa usindikaji wa moja kwa moja. Lakini vipi kuhusu nyenzo halisi ya mtihani uliyojifunza? Pengine ilihitaji kazi nyingi na tahadhari kwa sehemu yako ili kuingiza habari hiyo. Hii inajulikana kama usindikaji juhudi.

Je! Ni njia zenye ufanisi zaidi za kuhakikisha kuwa kumbukumbu muhimu zimehifadhiwa vizuri? Hata sentensi rahisi ni rahisi kukumbuka wakati ina maana (Anderson, 1984). Soma hukumu zifuatazo (Bransford & McCarrell, 1974), kisha uangalie mbali na uhesabu nyuma kutoka\(30\) kwa threes hadi sifuri, na kisha jaribu kuandika sentensi (hakuna peeking nyuma katika ukurasa huu!).

- Maelezo yalikuwa mabaya kwa sababu seams imegawanyika.

- Safari hiyo haikuchelewa kwa sababu chupa ilivunjika.

- Haystack ilikuwa muhimu kwa sababu kitambaa kilichopasuka.

Jinsi gani ulifanya vizuri? Kwao wenyewe, taarifa ambazo umeandika zilikuwa zinawezekana kuchanganya na vigumu kwako kukumbuka. Sasa, jaribu kuandika tena, ukitumia maelekezo yafuatayo: bagpipe, christening ya meli, na parachutist. Next kuhesabu nyuma kutoka\(40\) kwa nne, kisha kuangalia mwenyewe kuona jinsi vizuri alikumbuka hukumu wakati huu. Unaweza kuona kwamba sentensi sasa ni zaidi ya kukumbukwa kwa sababu kila moja ya sentensi iliwekwa katika muktadha. Nyenzo ni bora encoded wakati wewe kufanya hivyo maana.

Kuna aina tatu za encoding. Encoding ya maneno na maana yake inajulikana kama encoding semantic. Ilionyeshwa mara ya kwanza na William Bousfield (1935) katika jaribio ambalo aliwaomba watu kukariri maneno. \(60\)Maneno hayo yaligawanywa katika makundi 4 ya maana, ingawa washiriki hawakujua hili kwa sababu maneno yaliwasilishwa kwa nasibu. Walipoulizwa kukumbuka maneno hayo, walijitahidi kuyakumbuka katika makundi, wakionyesha kwamba walizingatia maana za maneno kama walivyojifunza.

Usimbaji wa Visual ni encoding ya picha, na encoding ya acoustic ni encoding ya sauti, maneno hasa. Ili kuona jinsi encoding ya Visual inavyofanya kazi, soma juu ya orodha hii ya maneno: gari, ngazi, mbwa, ukweli, kitabu, thamani. Ikiwa uliulizwa baadaye kukumbuka maneno kutoka kwenye orodha hii, ni zipi ambazo unafikiri ungependa kukumbuka zaidi? Pengine ungependa kuwa na wakati rahisi kukumbuka maneno gari, mbwa, na kitabu, na wakati mgumu zaidi kukumbuka maneno ngazi, ukweli, na thamani. Kwa nini hii? Kwa sababu unaweza kukumbuka picha (picha za akili) kwa urahisi zaidi kuliko maneno pekee. Unaposoma maneno gari, mbwa, na kitabu umetengeneza picha za mambo haya katika akili yako. Hizi ni maneno halisi, ya juu ya picha. Kwa upande mwingine, maneno dhahania kama kiwango, ukweli, na thamani ni maneno ya chini ya picha. Maneno ya juu ya picha ni encoded wote kuibua na semantically (Paivio, 1986), hivyo kujenga kumbukumbu imara.

Sasa hebu tugeuke mawazo yetu kwa encoding ya acoustic Unaendesha gari lako na wimbo unakuja kwenye redio ambayo hujasikia katika\(10\) miaka angalau, lakini unaimba pamoja, ukikumbuka kila neno. Nchini Marekani, watoto mara nyingi kujifunza alfabeti kupitia wimbo, na wao kujifunza idadi ya siku katika kila mwezi kupitia wimbo: “Siku thelathini ina Septemba,/Aprili, Juni, na Novemba;/wengine wote wana thelathini na moja,/Save Februari, na siku ishirini na nane wazi,/Na ishirini na tisa kila leap mwaka.” Masomo haya ni rahisi kukumbuka kwa sababu ya encoding ya acoustic. Sisi encode sauti maneno kufanya. Hii ni sababu moja kwa nini mengi ya kile tunachofundisha watoto wadogo kinafanywa kupitia wimbo, wimbo, na rhythm.

Ni ipi kati ya aina tatu za encoding unafikiri ingekupa kumbukumbu bora ya habari za maneno? Miaka michache iliyopita, wanasaikolojia Fergus Craik na Endel Tulving (1975) walifanya mfululizo wa majaribio ili kujua. Washiriki walipewa maneno pamoja na maswali juu yao. Maswali yalihitaji washiriki kusindika maneno katika moja ya ngazi tatu. Maswali ya usindikaji wa visu yalijumuisha mambo kama vile kuuliza washiriki kuhusu font ya barua. Maswali ya usindikaji wa acoustic aliwauliza washiriki kuhusu sauti au sauti ya maneno, na maswali ya usindikaji wa semantic aliwauliza washiriki kuhusu maana ya maneno. Baada ya washiriki kuwasilishwa kwa maneno na maswali, walipewa kazi ya kukumbuka au kutambuliwa zisizotarajiwa.

Maneno ambayo yamekuwa encoded semantically yalikumbuka vizuri zaidi kuliko wale encoded kuibua au acoustically. Usimbaji wa semantic unahusisha kiwango cha kina cha usindikaji kuliko encoding isiyoonekana au ya acoustic. Craik na Tulving walihitimisha kuwa tunachunguza habari za maneno bora kwa njia ya encoding ya semantic, hasa ikiwa tunatumia kile kinachoitwa athari ya kujitegemea. Athari ya kujitegemea ni tabia ya mtu binafsi kuwa na kumbukumbu bora kwa habari inayohusiana na nafsi ikilinganishwa na nyenzo ambazo zina umuhimu mdogo wa kibinafsi (Rogers, Kuiper & Kirker, 1977). Je, encoding ya semantic inaweza kuwa na manufaa kwako unapojaribu kukariri dhana katika sura hii?

Storage

Once the information has been encoded, we have to somehow have to retain it. Our brains take the encoded information and place it in storage. Storage is the creation of a permanent record of information.

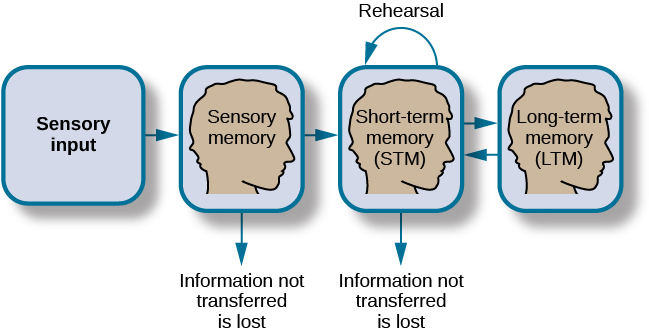

In order for a memory to go into storage (i.e., long-term memory), it has to pass through three distinct stages: Sensory Memory, Short-Term Memory, and finally Long-Term Memory. These stages were first proposed by Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin (1968). Their model of human memory, called Atkinson-Shiffrin (A-S), is based on the belief that we process memories in the same way that a computer processes information.

But A-S is just one model of memory. Others, such as Baddeley and Hitch (1974), have proposed a model where short-term memory itself has different forms. In this model, storing memories in short-term memory is like opening different files on a computer and adding information. The type of short-term memory (or computer file) depends on the type of information received. There are memories in visual-spatial form, as well as memories of spoken or written material, and they are stored in three short-term systems: a visuospatial sketchpad, an episodic buffer, and a phonological loop. According to Baddeley and Hitch, a central executive part of memory supervises or controls the flow of information to and from the three short-term systems.

Sensory Memory

In the Atkinson-Shiffrin model, stimuli from the environment are processed first in sensory memory: storage of brief sensory events, such as sights, sounds, and tastes. It is very brief storage—up to a couple of seconds. We are constantly bombarded with sensory information. We cannot absorb all of it, or even most of it. And most of it has no impact on our lives. For example, what was your professor wearing the last class period? As long as the professor was dressed appropriately, it does not really matter what she was wearing. Sensory information about sights, sounds, smells, and even textures, which we do not view as valuable information, we discard. If we view something as valuable, the information will move into our short-term memory system.

One study of sensory memory researched the significance of valuable information on short-term memory storage. J. R. Stroop discovered a memory phenomenon in the 1930s: you will name a color more easily if it appears printed in that color, which is called the Stroop effect. In other words, the word “red” will be named more quickly, regardless of the color the word appears in, than any word that is colored red. Try an experiment: name the colors of the words you are given in Figure. Do not read the words, but say the color the word is printed in. For example, upon seeing the word “yellow” in green print, you should say “green,” not “yellow.” This experiment is fun, but it’s not as easy as it seems.

Short-Term Memory

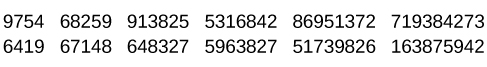

Short-term memory (STM) is a temporary storage system that processes incoming sensory memory; sometimes it is called working memory. Short-term memory takes information from sensory memory and sometimes connects that memory to something already in long-term memory. Short-term memory storage lasts about \(20\) seconds. George Miller (1956), in his research on the capacity of memory, found that most people can retain about \(7\) items in STM. Some remember \(5\), some \(9\), so he called the capacity of STM \(7\) plus or minus \(2\).

Think of short-term memory as the information you have displayed on your computer screen—a document, a spreadsheet, or a web page. Then, information in short-term memory goes to long-term memory (you save it to your hard drive), or it is discarded (you delete a document or close a web browser). This step of rehearsal, the conscious repetition of information to be remembered, to move STM into long-term memory is called memory consolidation.

You may find yourself asking, “How much information can our memory handle at once?” To explore the capacity and duration of your short-term memory, have a partner read the strings of random numbers out loud to you, beginning each string by saying, “Ready?” and ending each by saying, “Recall,” at which point you should try to write down the string of numbers from memory.

Note the longest string at which you got the series correct. For most people, this will be close to \(7\), Miller’s famous \(7\) plus or minus \(2\). Recall is somewhat better for random numbers than for random letters (Jacobs, 1887), and also often slightly better for information we hear (acoustic encoding) rather than see (visual encoding) (Anderson, 1969).

Long-term Memory

Long-term memory (LTM) is the continuous storage of information. Unlike short-term memory, the storage capacity of LTM has no limits. It encompasses all the things you can remember that happened more than just a few minutes ago to all of the things that you can remember that happened days, weeks, and years ago. In keeping with the computer analogy, the information in your LTM would be like the information you have saved on the hard drive. It isn’t there on your desktop (your short-term memory), but you can pull up this information when you want it, at least most of the time. Not all long-term memories are strong memories. Some memories can only be recalled through prompts. For example, you might easily recall a fact— “What is the capital of the United States?”—or a procedure—“How do you ride a bike?”—but you might struggle to recall the name of the restaurant you had dinner when you were on vacation in France last summer. A prompt, such as that the restaurant was named after its owner, who spoke to you about your shared interest in soccer, may help you recall the name of the restaurant.

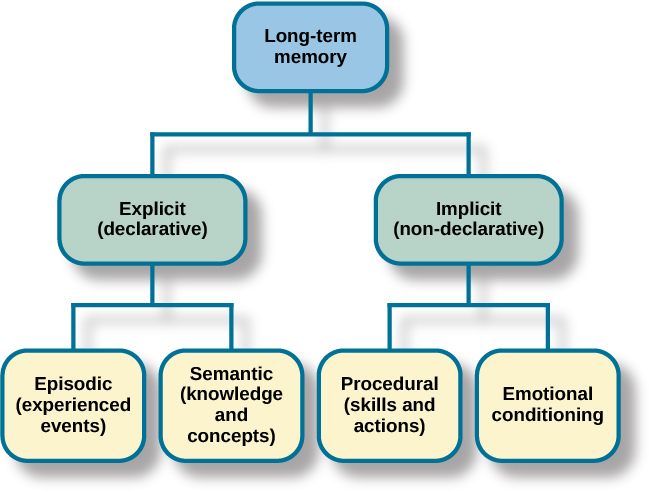

Long-term memory is divided into two types: explicit and implicit. Understanding the different types is important because a person’s age or particular types of brain trauma or disorders can leave certain types of LTM intact while having disastrous consequences for other types. Explicit memories are those we consciously try to remember and recall. For example, if you are studying for your chemistry exam, the material you are learning will be part of your explicit memory. (Note: Sometimes, but not always, the terms explicit memory and declarative memory are used interchangeably.)

Implicit memories are memories that are not part of our consciousness. They are memories formed from behaviors. Implicit memory is also called non-declarative memory.

Procedural memory is a type of implicit memory: it stores information about how to do things. It is the memory for skilled actions, such as how to brush your teeth, how to drive a car, how to swim the crawl (freestyle) stroke. If you are learning how to swim freestyle, you practice the stroke: how to move your arms, how to turn your head to alternate breathing from side to side, and how to kick your legs. You would practice this many times until you become good at it. Once you learn how to swim freestyle and your body knows how to move through the water, you will never forget how to swim freestyle, even if you do not swim for a couple of decades. Similarly, if you present an accomplished guitarist with a guitar, even if he has not played in a long time, he will still be able to play quite well.

Declarative memory has to do with the storage of facts and events we personally experienced. Explicit (declarative) memory has two parts: semantic memory and episodic memory. Semantic means having to do with language and knowledge about language. An example would be the question “what does argumentative mean?” Stored in our semantic memory is knowledge about words, concepts, and language-based knowledge and facts. For example, answers to the following questions are stored in your semantic memory:

- Who was the first President of the United States?

- What is democracy?

- What is the longest river in the world?

Episodic memory is information about events we have personally experienced. The concept of episodic memory was first proposed about \(40\) years ago (Tulving, 1972). Since then, Tulving and others have looked at scientific evidence and reformulated the theory. Currently, scientists believe that episodic memory is memory about happenings in particular places at particular times, the what, where, and when of an event (Tulving, 2002). It involves recollection of visual imagery as well as the feeling of familiarity (Hassabis & Maguire, 2007).

EVERYDAY CONNECTIONS: Can You Remember Everything You Ever Did or Said?

Episodic memories are also called autobiographical memories. Let’s quickly test your autobiographical memory. What were you wearing exactly five years ago today? What did you eat for lunch on April 10, 2009? You probably find it difficult, if not impossible, to answer these questions. Can you remember every event you have experienced over the course of your life—meals, conversations, clothing choices, weather conditions, and so on? Most likely none of us could even come close to answering these questions; however, American actress Marilu Henner, best known for the television show Taxi, can remember. She has an amazing and highly superior autobiographical memory.

Very few people can recall events in this way; right now, only \(12\) known individuals have this ability, and only a few have been studied (Parker, Cahill & McGaugh 2006). And although hyperthymesia normally appears in adolescence, two children in the United States appear to have memories from well before their tenth birthdays.

Retrieval

So you have worked hard to encode (via effortful processing) and store some important information for your upcoming final exam. How do you get that information back out of storage when you need it? The act of getting information out of memory storage and back into conscious awareness is known as retrieval. This would be similar to finding and opening a paper you had previously saved on your computer’s hard drive. Now it’s back on your desktop, and you can work with it again. Our ability to retrieve information from long-term memory is vital to our everyday functioning. You must be able to retrieve information from memory in order to do everything from knowing how to brush your hair and teeth, to driving to work, to knowing how to perform your job once you get there.

There are three ways you can retrieve information out of your long-term memory storage system: recall, recognition, and relearning. Recall is what we most often think about when we talk about memory retrieval: it means you can access information without cues. For example, you would use recall for an essay test. Recognition happens when you identify information that you have previously learned after encountering it again. It involves a process of comparison. When you take a multiple-choice test, you are relying on recognition to help you choose the correct answer. Here is another example. Let’s say you graduated from high school 10 years ago, and you have returned to your hometown for your 10-year reunion. You may not be able to recall all of your classmates, but you recognize many of them based on their yearbook photos.

The third form of retrieval is relearning, and it’s just what it sounds like. It involves learning information that you previously learned. Whitney took Spanish in high school, but after high school she did not have the opportunity to speak Spanish. Whitney is now 31, and her company has offered her an opportunity to work in their Mexico City office. In order to prepare herself, she enrolls in a Spanish course at the local community center. She’s surprised at how quickly she’s able to pick up the language after not speaking it for 13 years; this is an example of relearning.

Summary

Memory is a system or process that stores what we learn for future use.

Our memory has three basic functions: encoding, storing, and retrieving information. Encoding is the act of getting information into our memory system through automatic or effortful processing. Storage is retention of the information, and retrieval is the act of getting information out of storage and into conscious awareness through recall, recognition, and relearning. The idea that information is processed through three memory systems is called the Atkinson-Shiffrin (A-S) model of memory. First, environmental stimuli enter our sensory memory for a period of less than a second to a few seconds. Those stimuli that we notice and pay attention to then move into short-term memory (also called working memory). According to the A-S model, if we rehearse this information, then it moves into long-term memory for permanent storage. Other models like that of Baddeley and Hitch suggest there is more of a feedback loop between short-term memory and long-term memory. Long-term memory has a practically limitless storage capacity and is divided into implicit and explicit memory. Finally, retrieval is the act of getting memories out of storage and back into conscious awareness. This is done through recall, recognition, and relearning.

Glossary

- acoustic encoding

- input of sounds, words, and music

- Atkinson-Shiffrin model (A-S)

- memory model that states we process information through three systems: sensory memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory

- automatic processing

- encoding of informational details like time, space, frequency, and the meaning of words

- declarative memory

- type of long-term memory of facts and events we personally experience

- effortful processing

- encoding of information that takes effort and attention

- encoding

- input of information into the memory system

- episodic memory

- type of declarative memory that contains information about events we have personally experienced, also known as autobiographical memory

- explicit memory

- memories we consciously try to remember and recall

- implicit memory

- memories that are not part of our consciousness

- long-term memory (LTM)

- continuous storage of information

- memory

- system or process that stores what we learn for future use

- memory consolidation

- active rehearsal to move information from short-term memory into long-term memory

- procedural memory

- type of long-term memory for making skilled actions, such as how to brush your teeth, how to drive a car, and how to swim

- recall

- accessing information without cues

- recognition

- identifying previously learned information after encountering it again, usually in response to a cue

- rehearsal

- conscious repetition of information to be remembered

- relearning

- learning information that was previously learned

- retrieval

- act of getting information out of long-term memory storage and back into conscious awareness

- self-reference effect

- tendency for an individual to have better memory for information that relates to oneself in comparison to material that has less personal relevance

- semantic encoding

- input of words and their meaning

- semantic memory

- type of declarative memory about words, concepts, and language-based knowledge and facts

- sensory memory

- storage of brief sensory events, such as sights, sounds, and tastes

- short-term memory (STM)

- (also, working memory) holds about seven bits of information before it is forgotten or stored, as well as information that has been retrieved and is being used

- storage

- creation of a permanent record of information

- visual encoding

- input of images