43.6: Fertilização e desenvolvimento embrionário precoce

- Page ID

- 182096

Habilidades para desenvolver

- Discuta como ocorre a fertilização

- Explique como o embrião se forma a partir do zigoto

- Discuta o papel da clivagem e gastrulação no desenvolvimento animal

O processo no qual um organismo se desenvolve de um zigoto unicelular para um organismo multicelular é complexo e bem regulado. Os estágios iniciais do desenvolvimento embrionário também são cruciais para garantir a aptidão do organismo.

Fertilização

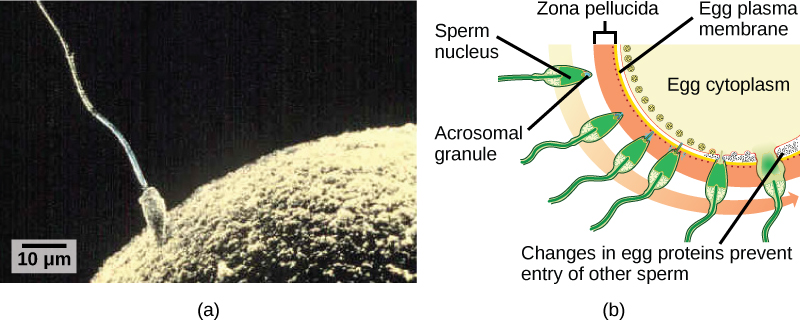

A fertilização, ilustrada na Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\) a, é o processo no qual os gametas (um óvulo e um espermatozóide) se fundem para formar um zigoto. O óvulo e o espermatozóide contêm, cada um, um conjunto de cromossomos. Para garantir que a prole tenha apenas um conjunto diploide completo de cromossomos, apenas um espermatozóide deve se fundir com um óvulo. Em mamíferos, o ovo é protegido por uma camada de matriz extracelular composta principalmente por glicoproteínas chamada zona pelúcida. Quando um espermatozóide se liga à zona pelúcida, ocorre uma série de eventos bioquímicos, chamados de reações acrossômicas. Em mamíferos placentários, o acrossoma contém enzimas digestivas que iniciam a degradação da matriz glicoproteica, protegendo o óvulo e permitindo que a membrana plasmática espermática se funda com a membrana plasmática do óvulo, conforme ilustrado na Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\) b. A fusão dessas duas membranas cria uma abertura através qual o núcleo do espermatozóide é transferido para o óvulo. As membranas nucleares do óvulo e do espermatozóide se quebram e os dois genomas haplóides se condensam para formar um genoma diploide.

Para garantir que não mais do que um espermatozóide fertilize o óvulo, uma vez que as reações acrossômicas ocorrem em um local da membrana do óvulo, o óvulo libera proteínas em outros locais para evitar que outros espermatozoides se fundam com o óvulo. Se esse mecanismo falhar, vários espermatozoides podem se fundir com o óvulo, resultando em polispermia. O embrião resultante não é geneticamente viável e morre em poucos dias.

Estágio de clivagem e blástula

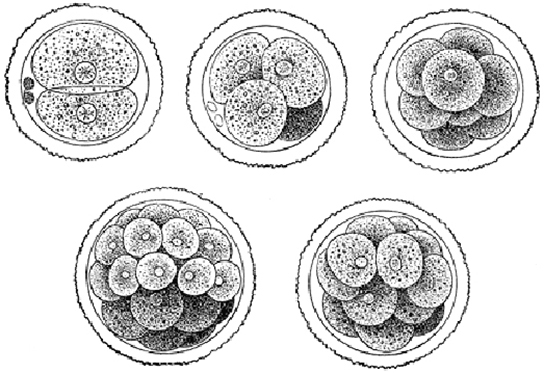

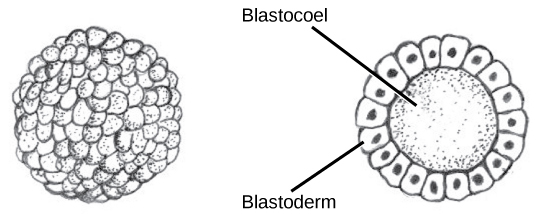

O desenvolvimento de organismos multicelulares começa a partir de um zigoto unicelular, que sofre uma rápida divisão celular para formar a blástula. As rápidas e múltiplas rodadas de divisão celular são chamadas de clivagem. A clivagem é ilustrada em (Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\) a). Depois que a clivagem produz mais de 100 células, o embrião é chamado de blástula. A blástula é geralmente uma camada esférica de células (o blastoderma) ao redor de uma cavidade cheia de líquido ou gema (o blastocoel). Os mamíferos nesse estágio formam uma estrutura chamada blastocisto, caracterizada por uma massa celular interna que é distinta da blástula circundante, mostrada na Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\) b. Durante a clivagem, as células se dividem sem aumento de massa; ou seja, um grande zigoto unicelular se divide em várias células menores . Cada célula dentro da blástula é chamada de blastômero.

A clivagem pode ocorrer de duas maneiras: clivagem holoblástica (total) ou clivagem meroblástica (parcial). O tipo de clivagem depende da quantidade de gema nos ovos. Em mamíferos placentários (incluindo humanos), onde a nutrição é fornecida pelo corpo da mãe, os ovos têm uma quantidade muito pequena de gema e sofrem clivagem holoblástica. Outras espécies, como pássaros, com muita gema no ovo para nutrir o embrião durante o desenvolvimento, sofrem clivagem meroblástica.

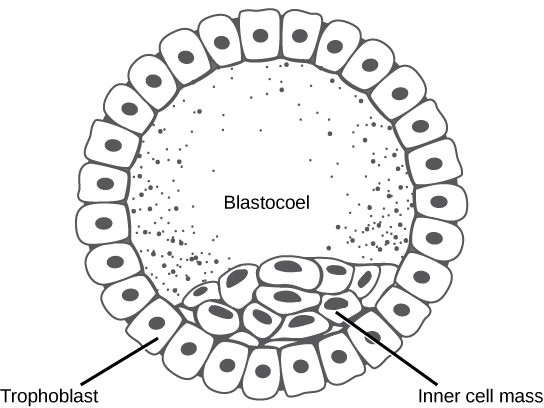

Nos mamíferos, a blástula forma o blastocisto no próximo estágio de desenvolvimento. Aqui, as células da blástula se organizam em duas camadas: a massa celular interna e uma camada externa chamada trofoblasto. A massa celular interna também é conhecida como embrioblasto e essa massa de células formará o embrião. Neste estágio de desenvolvimento, ilustrado na Figura,\(\PageIndex{3}\) a massa celular interna consiste em células-tronco embrionárias que se diferenciarão nos diferentes tipos de células necessários ao organismo. O trofoblasto contribuirá para a placenta e nutrirá o embrião.

Link para o aprendizado

Visite o projeto Virtual Human Embryo no site Endowment for Human Development para percorrer um programa interativo que mostra os estágios do desenvolvimento do embrião, incluindo micrografias e imagens 3D rotativas.

Gastrulação

A blástula típica é uma bola de células. O próximo estágio do desenvolvimento embrionário é a formação do plano corporal. As células da blástula se reorganizam espacialmente para formar três camadas de células. Esse processo é chamado de gastrulação. Durante a gastrulação, a blástula se dobra sobre si mesma para formar as três camadas de células. Cada uma dessas camadas é chamada de camada germinativa e cada camada germinativa se diferencia em diferentes sistemas orgânicos.

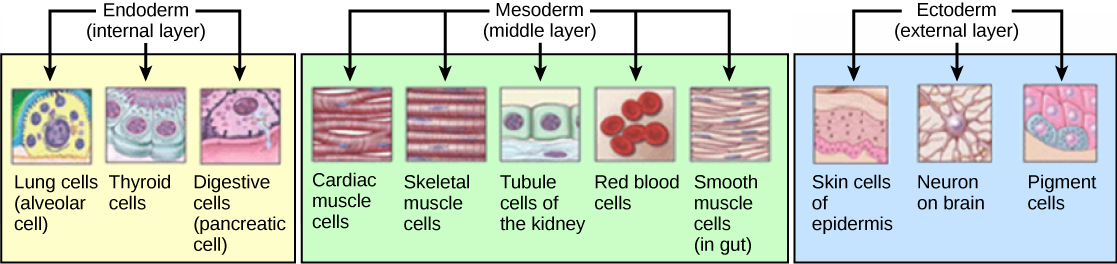

As três camadas de germes, mostradas na Figura\(\PageIndex{4}\), are the endoderm, the ectoderm, and the mesoderm. The ectoderm gives rise to the nervous system and the epidermis. The mesoderm gives rise to the muscle cells and connective tissue in the body. The endoderm gives rise to columnar cells found in the digestive system and many internal organs.

Everyday Connection: Are Designer Babies in Our Future?

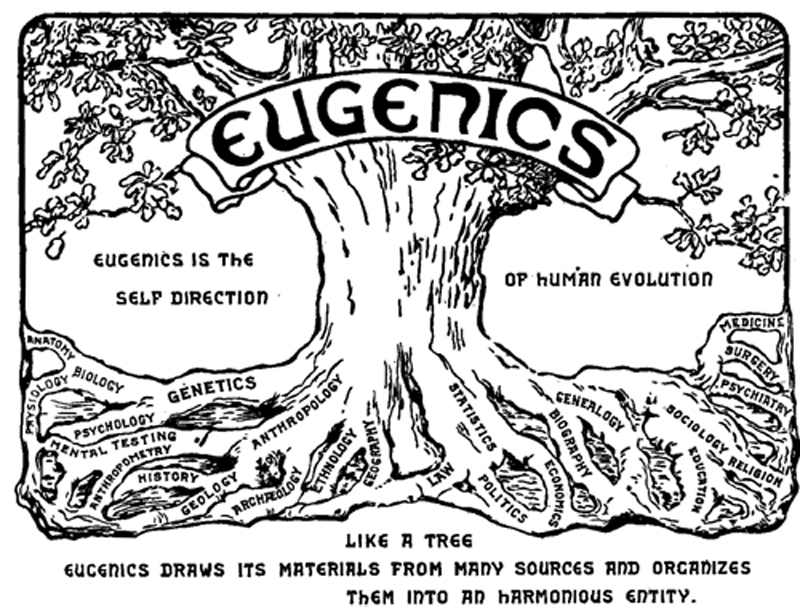

If you could prevent your child from getting a devastating genetic disease, would you do it? Would you select the sex of your child or select for their attractiveness, strength, or intelligence? How far would you go to maximize the possibility of resistance to disease? The genetic engineering of a human child, the production of "designer babies" with desirable phenotypic characteristics, was once a topic restricted to science fiction. This is the case no longer: science fiction is now overlapping into science fact. Many phenotypic choices for offspring are already available, with many more likely to be possible in the not too distant future. Which traits should be selected and how they should be selected are topics of much debate within the worldwide medical community. The ethical and moral line is not always clear or agreed upon, and some fear that modern reproductive technologies could lead to a new form of eugenics.

Eugenics is the use of information and technology from a variety of sources to improve the genetic makeup of the human race. The goal of creating genetically superior humans was quite prevalent (although controversial) in several countries during the early 20th century, but fell into disrepute when Nazi Germany developed an extensive eugenics program in the 1930's and 40's. As part of their program, the Nazis forcibly sterilized hundreds of thousands of the so-called "unfit" and killed tens of thousands of institutionally disabled people as part of a systematic program to develop a genetically superior race of Germans known as Aryans. Ever since, eugenic ideas have not been as publicly expressed, but there are still those who promote them.

Efforts have been made in the past to control traits in human children using donated sperm from men with desired traits. In fact, eugenicist Robert Klark Graham established a sperm bank in 1980 that included samples exclusively from donors with high IQs. The "genius" sperm bank failed to capture the public's imagination and the operation closed in 1999.

In more recent times, the procedure known as prenatal genetic diagnosis (PGD) has been developed. PGD involves the screening of human embryos as part of the process of in vitro fertilization, during which embryos are conceived and grown outside the mother's body for some period of time before they are implanted. The term PGD usually refers to both the diagnosis, selection, and the implantation of the selected embryos.

In the least controversial use of PGD, embryos are tested for the presence of alleles which cause genetic diseases such as sickle cell disease, muscular dystrophy, and hemophilia, in which a single disease-causing allele or pair of alleles has been identified. By excluding embryos containing these alleles from implantation into the mother, the disease is prevented, and the unused embryos are either donated to science or discarded. There are relatively few in the worldwide medical community that question the ethics of this type of procedure, which allows individuals scared to have children because of the alleles they carry to do so successfully. The major limitation to this procedure is its expense. Not usually covered by medical insurance and thus out of reach financially for most couples, only a very small percentage of all live births use such complicated methodologies. Yet, even in cases like these where the ethical issues may seem to be clear-cut, not everyone agrees with the morality of these types of procedures. For example, to those who take the position that human life begins at conception, the discarding of unused embryos, a necessary result of PGD, is unacceptable under any circumstances.

A murkier ethical situation is found in the selection of a child's sex, which is easily performed by PGD. Currently, countries such as Great Britain have banned the selection of a child's sex for reasons other than preventing sex-linked diseases. Other countries allow the procedure for "family balancing", based on the desire of some parents to have at least one child of each sex. Still others, including the United States, have taken a scattershot approach to regulating these practices, essentially leaving it to the individual practicing physician to decide which practices are acceptable and which are not.

Even murkier are rare instances of disabled parents, such as those with deafness or dwarfism, who select embryos via PGD to ensure that they share their disability. These parents usually cite many positive aspects of their disabilities and associated culture as reasons for their choice, which they see as their moral right. To others, to purposely cause a disability in a child violates the basic medical principle of Primum non nocere, "first, do no harm." This procedure, although not illegal in most countries, demonstrates the complexity of ethical issues associated with choosing genetic traits in offspring.

Where could this process lead? Will this technology become more affordable and how should it be used? With the ability of technology to progress rapidly and unpredictably, a lack of definitive guidelines for the use of reproductive technologies before they arise might make it difficult for legislators to keep pace once they are in fact realized, assuming the process needs any government regulation at all. Other bioethicists argue that we should only deal with technologies that exist now, and not in some uncertain future. They argue that these types of procedures will always be expensive and rare, so the fears of eugenics and "master" races are unfounded and overstated. The debate continues.

Summary

The early stages of embryonic development begin with fertilization. The process of fertilization is tightly controlled to ensure that only one sperm fuses with one egg. After fertilization, the zygote undergoes cleavage to form the blastula. The blastula, which in some species is a hollow ball of cells, undergoes a process called gastrulation, in which the three germ layers form. The ectoderm gives rise to the nervous system and the epidermal skin cells, the mesoderm gives rise to the muscle cells and connective tissue in the body, and the endoderm gives rise to columnar cells and internal organs.

Glossary

- acrosomal reaction

- series of biochemical reactions that the sperm uses to break through the zona pellucida

- blastocyst

- structure formed when cells in the mammalian blastula separate into an inner and outer layer

- gastrulation

- process in which the blastula folds over itself to form the three germ layers

- holoblastic

- complete cleavage; takes place in cells with a small amount of yolk

- inner cell mass

- inner layer of cells in the blastocyst

- meroblastic

- partial cleavage; takes place in cells with a large amount of yolk

- polyspermy

- condition in which one egg is fertilized by multiple sperm

- trophoblast

- outer layer of cells in the blastocyst

- zona pellucida

- protective layer of glycoproteins on the mammalian egg