7.4 : Résolution de problèmes

- Page ID

- 190227

Objectifs d'apprentissage

- Décrire les stratégies de résolution de

- Définir l'algorithme et l'heuristique

- Expliquer certains obstacles courants à la résolution efficace des problèmes

Les gens font face à des problèmes tous les jours, généralement de multiples problèmes tout au long de la journée. Parfois, ces problèmes sont simples : pour doubler une recette de pâte à pizza, par exemple, il suffit de doubler chaque ingrédient de la recette. Cependant, les problèmes que nous rencontrons sont parfois plus complexes. Par exemple, supposons que vous ayez une date limite de travail et que vous deviez envoyer une copie imprimée d'un rapport à votre superviseur avant la fin de la journée ouvrable. Le rapport est urgent et doit être envoyé du jour au lendemain. Vous avez terminé le rapport hier soir, mais votre imprimante ne fonctionnera pas aujourd'hui. Que devez-vous faire ? Vous devez d'abord identifier le problème, puis appliquer une stratégie pour le résoudre.

Stratégies de résolution de problèmes

Lorsque vous êtes confronté à un problème, qu'il s'agisse d'un problème mathématique complexe ou d'une imprimante défectueuse, comment le résolvez-vous ? Avant de trouver une solution au problème, celui-ci doit d'abord être clairement identifié. Ensuite, l'une des nombreuses stratégies de résolution de problèmes peut être appliquée et, espérons-le, aboutir à une solution.

Une stratégie de résolution de problèmes est un plan d'action utilisé pour trouver une solution. Différentes stratégies sont associées à des plans d'action différents (voir le tableau\(\PageIndex{1}\) ci-dessous). Par exemple, une stratégie bien connue est celle des essais et des erreurs. Le vieil adage « Si au début vous ne réussissez pas, essayez, réessayez » décrit les essais et les erreurs. En ce qui concerne votre imprimante cassée, vous pouvez essayer de vérifier le niveau d'encre et, si cela ne fonctionne pas, vous pouvez vous assurer que le bac à papier n'est pas bloqué. Ou peut-être que l'imprimante n'est pas réellement connectée à votre ordinateur portable. Lorsque vous utilisez des essais et des erreurs, vous continueriez à essayer différentes solutions jusqu'à ce que vous résolviez votre problème. Bien que les essais et les erreurs ne soient généralement pas l'une des stratégies les plus rapides, c'est une stratégie couramment utilisée.

| Méthode | Désignation | Exemple |

|---|---|---|

| Essais et erreurs | Continuez à essayer différentes solutions jusqu'à ce que le problème soit résolu | Redémarrer le téléphone, désactiver le Wi-Fi, désactiver le Bluetooth afin de déterminer la raison du dysfonctionnement de votre téléphone |

| algorithme | Formule de résolution de problèmes étape par étape | Manuel d'instructions pour l'installation de nouveaux logiciels sur votre ordinateur |

| Heuristique | Cadre général de résolution de problèmes | Travail à rebours ; division d'une tâche en étapes |

Un autre type de stratégie est l'algorithme. Un algorithme est une formule de résolution de problèmes qui vous fournit des instructions étape par étape pour obtenir le résultat souhaité (Kahneman, 2011). Vous pouvez considérer un algorithme comme une recette avec des instructions très détaillées qui produisent le même résultat à chaque fois qu'elles sont exécutées. Les algorithmes sont fréquemment utilisés dans notre vie quotidienne, notamment en informatique. Lorsque vous effectuez une recherche sur Internet, les moteurs de recherche tels que Google utilisent des algorithmes pour déterminer quelles entrées apparaîtront en premier dans votre liste de résultats. Facebook utilise également des algorithmes pour choisir les publications à afficher sur votre fil d'actualité. Pouvez-vous identifier d'autres situations dans lesquelles des algorithmes sont utilisés ?

L'heuristique est un autre type de stratégie de résolution de problèmes. Alors qu'un algorithme doit être suivi à la lettre pour obtenir un résultat correct, une heuristique est un cadre général de résolution de problèmes (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). Vous pouvez les considérer comme des raccourcis mentaux utilisés pour résoudre des problèmes. Une « règle empirique » est un exemple d'heuristique. Une telle règle permet à la personne de gagner du temps et de l'énergie lorsqu'elle prend une décision, mais malgré ses caractéristiques de gain de temps, ce n'est pas toujours la meilleure méthode pour prendre une décision rationnelle. Différents types d'heuristiques sont utilisés dans différents types de situations, mais l'envie d'utiliser une heuristique se produit lorsque l'une des cinq conditions suivantes est remplie (Pratkanis, 1989) :

- Quand on est confronté à trop d'informations

- Quand le temps de prendre une décision est limité

- Quand la décision à prendre est sans importance

- Lorsqu'on a accès à très peu d'informations à utiliser pour prendre une décision

- Quand une heuristique appropriée vient à l'esprit au même moment

Le travail à rebours est une heuristique utile dans laquelle vous commencez à résoudre le problème en vous concentrant sur le résultat final. Prenons cet exemple : vous vivez à Washington, D.C. et vous avez été invité à un mariage\(\text{4 PM}\) samedi à Philadelphie. Sachant que l'Interstate\(95\) a tendance à reculer tous les jours de la semaine, vous devez planifier votre itinéraire et planifier votre départ en conséquence. Si vous voulez assister au service de mariage et qu'il faut des\(2.5\) heures pour vous rendre à Philadelphie sans circulation, à quelle heure devez-vous quitter votre maison ?\(\text{3:30 PM}\) Vous utilisez l'heuristique du travail à rebours pour planifier régulièrement les événements de votre journée, probablement sans même y penser.

Une autre heuristique utile est la pratique qui consiste à accomplir un objectif ou une tâche de grande envergure en le divisant en une série d'étapes plus petites. Les étudiants utilisent souvent cette méthode courante pour réaliser un grand projet de recherche ou une longue dissertation pour l'école. Par exemple, les étudiants réfléchissent généralement, élaborent une thèse ou un sujet principal, font des recherches sur le sujet choisi, organisent leurs informations dans un plan, rédigent une ébauche, révisent et modifient l'ébauche, élaborent une ébauche finale, organisent la liste de références et corrigent leur travail avant de soumettre le projet. La tâche importante devient moins accablante lorsqu'elle est divisée en une série de petites étapes.

EVERYDAY CONNECTION: Solving Puzzles

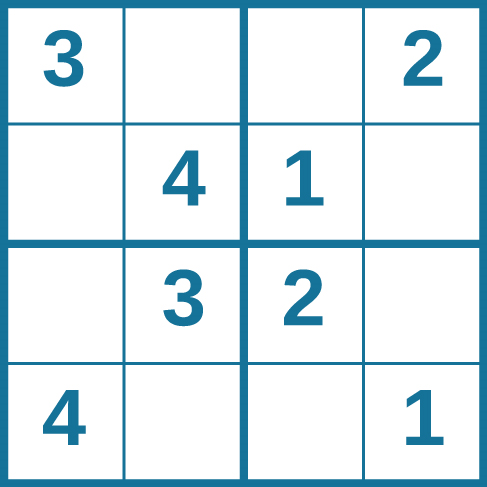

Problem-solving abilities can improve with practice. Many people challenge themselves every day with puzzles and other mental exercises to sharpen their problem-solving skills. Sudoku puzzles appear daily in most newspapers. Typically, a sudoku puzzle is a \(9\times 9\) grid. The simple sudoku below is a \(4\times 4\) grid. To solve the puzzle, fill in the empty boxes with a single digit: \(1\), \(2\), \(3\), or \(4\). Here are the rules: The numbers must total \(10\) in each bolded box, each row, and each column; however, each digit can only appear once in a bolded box, row, and column. Time yourself as you solve this puzzle and compare your time with a classmate.

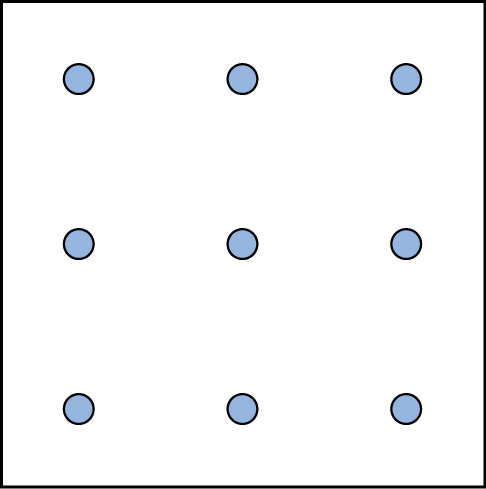

Here is another popular type of puzzle that challenges your spatial reasoning skills. Connect all nine dots with four connecting straight lines without lifting your pencil from the paper:

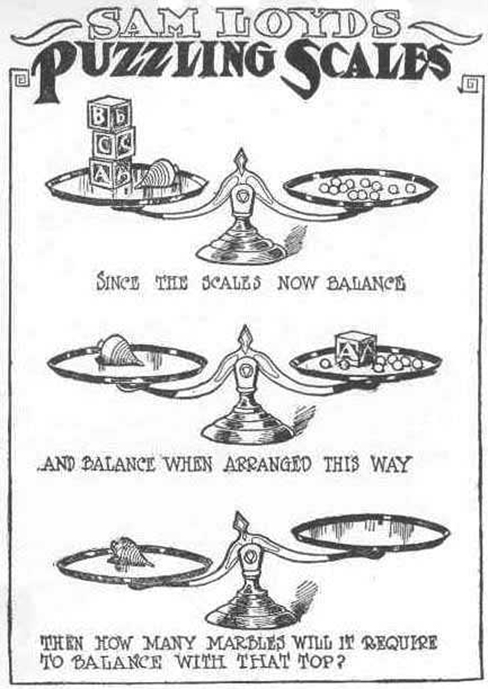

Take a look at the “Puzzling Scales” logic puzzle below. Sam Loyd, a well-known puzzle master, created and refined countless puzzles throughout his lifetime (Cyclopedia of Puzzles, n.d.).

Pitfalls to Problem Solving

Not all problems are successfully solved, however. What challenges stop us from successfully solving a problem? Albert Einstein once said, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.” Imagine a person in a room that has four doorways. One doorway that has always been open in the past is now locked. The person, accustomed to exiting the room by that particular doorway, keeps trying to get out through the same doorway even though the other three doorways are open. The person is stuck—but she just needs to go to another doorway, instead of trying to get out through the locked doorway. A mental set is where you persist in approaching a problem in a way that has worked in the past but is clearly not working now.

Functional fixedness is a type of mental set where you cannot perceive an object being used for something other than what it was designed for. During the Apollo 13 mission to the moon, NASA engineers at Mission Control had to overcome functional fixedness to save the lives of the astronauts aboard the spacecraft. An explosion in a module of the spacecraft damaged multiple systems. The astronauts were in danger of being poisoned by rising levels of carbon dioxide because of problems with the carbon dioxide filters. The engineers found a way for the astronauts to use spare plastic bags, tape, and air hoses to create a makeshift air filter, which saved the lives of the astronauts.

Researchers have investigated whether functional fixedness is affected by culture. In one experiment, individuals from the Shuar group in Ecuador were asked to use an object for a purpose other than that for which the object was originally intended. For example, the participants were told a story about a bear and a rabbit that were separated by a river and asked to select among various objects, including a spoon, a cup, erasers, and so on, to help the animals. The spoon was the only object long enough to span the imaginary river, but if the spoon was presented in a way that reflected its normal usage, it took participants longer to choose the spoon to solve the problem. (German & Barrett, 2005). The researchers wanted to know if exposure to highly specialized tools, as occurs with individuals in industrialized nations, affects their ability to transcend functional fixedness. It was determined that functional fixedness is experienced in both industrialized and nonindustrialized cultures (German & Barrett, 2005).

In order to make good decisions, we use our knowledge and our reasoning. Often, this knowledge and reasoning is sound and solid. Sometimes, however, we are swayed by biases or by others manipulating a situation. For example, let’s say you and three friends wanted to rent a house and had a combined target budget of \(\$1,600\). The realtor shows you only very run-down houses for \(\$1,600\) and then shows you a very nice house for \(\$2,000\). Might you ask each person to pay more in rent to get the \(\$2,000\) home? Why would the realtor show you the run-down houses and the nice house? The realtor may be challenging your anchoring bias. An anchoring bias occurs when you focus on one piece of information when making a decision or solving a problem. In this case, you’re so focused on the amount of money you are willing to spend that you may not recognize what kinds of houses are available at that price point.

The confirmation bias is the tendency to focus on information that confirms your existing beliefs. For example, if you think that your professor is not very nice, you notice all of the instances of rude behavior exhibited by the professor while ignoring the countless pleasant interactions he is involved in on a daily basis. Hindsight bias leads you to believe that the event you just experienced was predictable, even though it really wasn’t. In other words, you knew all along that things would turn out the way they did. Representative bias describes a faulty way of thinking, in which you unintentionally stereotype someone or something; for example, you may assume that your professors spend their free time reading books and engaging in intellectual conversation, because the idea of them spending their time playing volleyball or visiting an amusement park does not fit in with your stereotypes of professors.

Finally, the availability heuristic is a heuristic in which you make a decision based on an example, information, or recent experience that is that readily available to you, even though it may not be the best example to inform your decision. Biases tend to “preserve that which is already established—to maintain our preexisting knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and hypotheses” (Aronson, 1995; Kahneman, 2011). These biases are summarized in the Table \(\PageIndex{2}\) below.

| Bias | Description |

|---|---|

| Anchoring | Tendency to focus on one particular piece of information when making decisions or problem-solving |

| Confirmation | Focuses on information that confirms existing beliefs |

| Hindsight | Belief that the event just experienced was predictable |

| Representative | Unintentional stereotyping of someone or something |

| Availability | Decision is based upon either an available precedent or an example that may be faulty |

Were you able to determine how many marbles are needed to balance the scales in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)? You need nine.

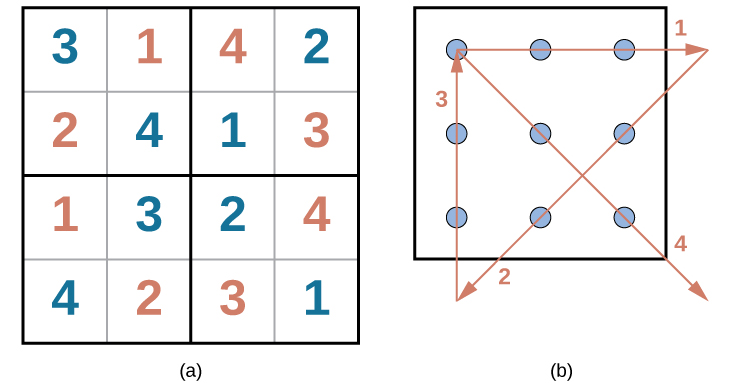

Were you able to solve the problems in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) and Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)? Here are the answers:

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Solutions to the puzzles in Everyday Connection

Summary

Many different strategies exist for solving problems. Typical strategies include trial and error, applying algorithms, and using heuristics. To solve a large, complicated problem, it often helps to break the problem into smaller steps that can be accomplished individually, leading to an overall solution. Roadblocks to problem solving include a mental set, functional fixedness, and various biases that can cloud decision making skills.

Glossary

- algorithm

- problem-solving strategy characterized by a specific set of instructions

- anchoring bias

- faulty heuristic in which you fixate on a single aspect of a problem to find a solution

- availability heuristic

- faulty heuristic in which you make a decision based on information readily available to you

- confirmation bias

- faulty heuristic in which you focus on information that confirms your beliefs

- functional fixedness

- inability to see an object as useful for any other use other than the one for which it was intended

- heuristic

- mental shortcut that saves time when solving a problem

- hindsight bias

- belief that the event just experienced was predictable, even though it really wasn’t

- mental set

- continually using an old solution to a problem without results

- problem-solving strategy

- method for solving problems

- representative bias

- faulty heuristic in which you stereotype someone or something without a valid basis for your judgment

- trial and error

- problem-solving strategy in which multiple solutions are attempted until the correct one is found

- working backwards

- heuristic in which you begin to solve a problem by focusing on the end result