33.1: 动物形态和功能

- Page ID

- 202554

培养技能

- 描述动物身上出现的各种类型的身体计划

- 描述动物大小和形状的限制

- 将生物能量学与体型、活动水平和环境联系起来

动物的形态和功能各不相同。 从海绵到蠕虫再到山羊,生物都有独特的身体计划,限制了其大小和形状。 动物的身体还被设计成与环境相互作用,无论是在深海、雨林树冠还是沙漠中。 因此,通过研究生物体的环境,可以学习有关该生物体体结构(解剖学)及其细胞、组织和器官(生理学)功能的大量信息。

身体计划

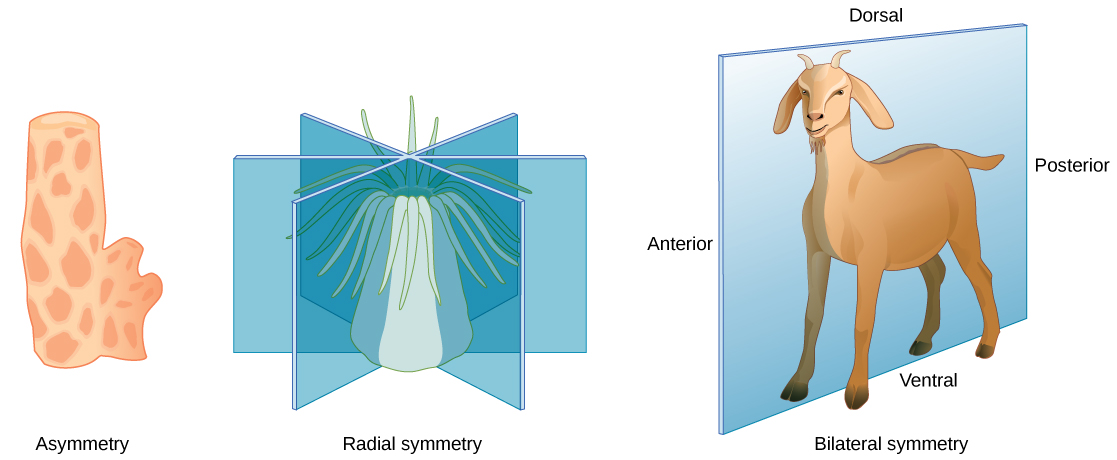

动物的身体计划遵循与对称性相关的固定模式。 它们的形式为非对称、径向或双侧,如图所示\(\PageIndex{1}\)。 不对称动物是指没有图案或对称性的动物;不对称动物的一个例子是海绵。 如图\(\PageIndex{1}\)所示,径向对称性描述了动物何时具有向上和向下方向:任何沿其纵向轴穿过生物体的平面都会产生相等的两半,但不是明确的右侧或左侧。 这种计划主要存在于水生动物身上,尤其是那些附着在基地(如岩石或船)上的生物,当食物在生物体周围流动时从周围的水中提取食物。 山羊在同一个图中说明了双边对称性。 山羊也有上部和下部的成分,但是从前到后切割的飞机将动物分为明确的左右两侧。 描述身体姿势时使用的其他术语是前(前)、后(后)、背部(朝后)和腹侧(朝向胃)。 在陆地和水生动物中都存在双向对称性;它可以实现高度的活动性。

动物大小和形状的限制

生活在水中的具有双向对称性的动物往往呈梭形状:这是一个管状的身体,两端呈锥形。 这种形状减少了身体在水中移动时的阻力,并允许动物高速游泳。 下表列出了各种动物的最大速度。 某些类型的鲨鱼可以以每小时五十公里的速度游泳,有些海豚可以以每小时 32 到 40 公里的速度游泳。 陆地动物的旅行速度通常更快,尽管乌龟和蜗牛比猎豹慢得多。 水生和陆地生物适应能力的另一个区别是,水生生物的形状受到水中阻力的限制,因为水的粘度高于空气。 另一方面,陆地生物主要受重力的限制,阻力相对不重要。 例如,鸟类的大多数改编都是为了重力而不是阻力。

| 动物 | 速度(公里/小时) | 速度(英里每小时) |

|---|---|---|

| 猎豹 | 113 | 70 |

| 四分之一马 | 77 | 48 |

| 福克斯 | 68 | 42 |

| Shortfin mako shark | 50 | 31 |

| 家养的家猫 | 48 | 30 |

| 人类 | 45 | 28 |

| 海豚 | 32—40 | 20—25 |

| 鼠标 | 13 | 8 |

| 蜗牛 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

大多数动物都有外骨骼,包括昆虫、蜘蛛、蝎子、马蹄蟹、萜类和甲壳类动物。 科学家估计,仅在昆虫中,我们星球上就有超过3000万种物种。 外骨骼是一种硬质覆盖物或外壳,可为动物提供益处,例如保护动物免受捕食者的伤害和水分流失(对于陆地动物);它还为肌肉提供了附着力。

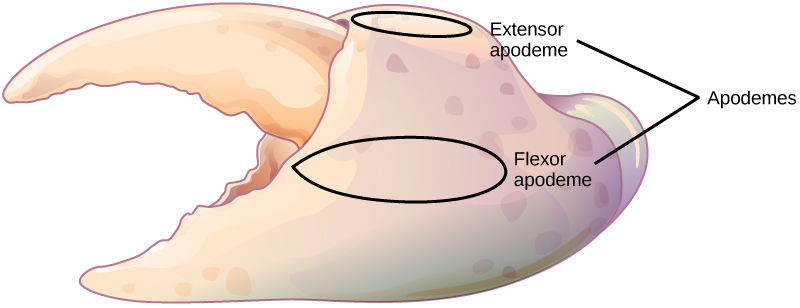

作为节肢动物坚固耐用的外壳,外骨骼可以由坚硬的聚合物(例如甲壳素)构成,并且通常使用碳酸钙等材料进行生物矿化。 这与动物的表皮融为一体。 外骨骼向内生长,称为 apodemes,充当肌肉的附着部位,类似于较高级动物的肌腱(图\(\PageIndex{2}\))。 为了生长,动物必须首先在旧的外骨骼下合成一个新的外骨骼,然后脱落或腐烂原来的覆盖物。 这限制了动物持续生长的能力,如果不在适当的时间发生蛀牙,则可能会限制个体的成熟能力。 必须显著增加外骨骼的厚度,以适应重量的增加。 据估计,体型翻倍会使体重增加八倍。 支撑这种体重所需的甲壳素厚度的增加限制了大多数具有外骨骼的动物体积相对较小。 同样的原理也适用于内骨骼,但它们的效率更高,因为肌肉附着在外面,因此更容易补偿增加的重量。

具有内骨骼的动物的大小取决于它支撑其他组织所需的骨骼系统量和运动所需的肌肉量。 随着体型的增加,骨骼和肌肉的质量都会增加。 动物可以达到的速度是其整体大小与提供支撑和运动的骨骼和肌肉之间的平衡。

扩散对规模和发育的限制影响

细胞与其水环境之间的营养物质和废物的交换是通过扩散过程发生的。 所有活细胞都沐浴在液体中,无论它们是在单细胞生物体还是多细胞生物体中。 扩散在特定距离内有效,并限制了单个细胞可以达到的大小。 如果一个细胞是单细胞微生物,例如变形虫,它可以通过扩散来满足其所有的营养和废物需求。 如果细胞太大,则扩散无效,细胞中心无法获得足够的营养,也无法有效驱散废物。

要理解扩散作为一种传输手段的效率如何,一个重要的概念是表面与体积的比例。 回想一下,任何三维物体都有表面积和体积;这两个量的比率是表面与体积的比例。 假设一个形状像完美球体的细胞:它的表面积为 4αr 2,体积为 (4/3) ωr 3。 球体的表面体积比为 3/r;随着细胞变大,其表面体积比会降低,从而降低扩散效率。 球体或动物的大小越大,它所拥有的扩散表面积就越小。

产生较大生物的解决方案是让它们变成多细胞。 专业化发生在复杂的生物体中,这使细胞能够在完成更少的任务时变得更有效。 例如,循环系统带来营养并清除废物,而呼吸系统为细胞提供氧气并去除细胞中的二氧化碳。 其他器官系统进一步发展了细胞和组织的专业化,并有效地控制了人体功能。 此外,表面体积比适用于动物发育的其他领域,例如支撑骨骼中肌肉质量与横截面表面积之间的关系,以及肌肉质量与热量消散之间的关系。

动物生物能量学

所有动物都必须从它们摄入或吸收的食物中获取能量。 这些营养素被转化为三磷酸腺苷(ATP),用于短期储存和供所有细胞使用。 有些动物作为糖原储存能量的时间稍长一些,而另一些动物则以甘油三酯的形式储存能量的时间要长得多。 没有哪个能量系统能百分之百地高效,动物的新陈代谢会产生热量的废弃能量。 如果动物能够保存热量并保持相对恒定的体温,则将其归类为温血动物,称为吸热动物。 用于保存身体热量的隔热材料以毛皮、脂肪或羽毛的形式出现。 外热动物缺乏隔热材料会增加它们对环境获取体温的依赖。

动物在特定时间消耗的能量称为其新陈代谢率。 该比率以焦耳、卡路里或千卡路里(1000 卡路里)来衡量。 碳水化合物和蛋白质含有大约4.5至5千卡/克,脂肪含有约9千卡/克。代谢率是根据静止吸热动物的基础代谢率(BMR)和外热中的标准代谢率(SMR)来估算的。 人类雄性的 BMR 为 1600 到 1800 千卡/天,人类雌性的 BMR 为 1300 至 1500 千卡/天。 即使使用隔热材料,内热动物也需要大量的能量来维持恒定的体温。 像鳄鱼这样的外热的SMR为60千卡/天。

与体型相关的能量需求

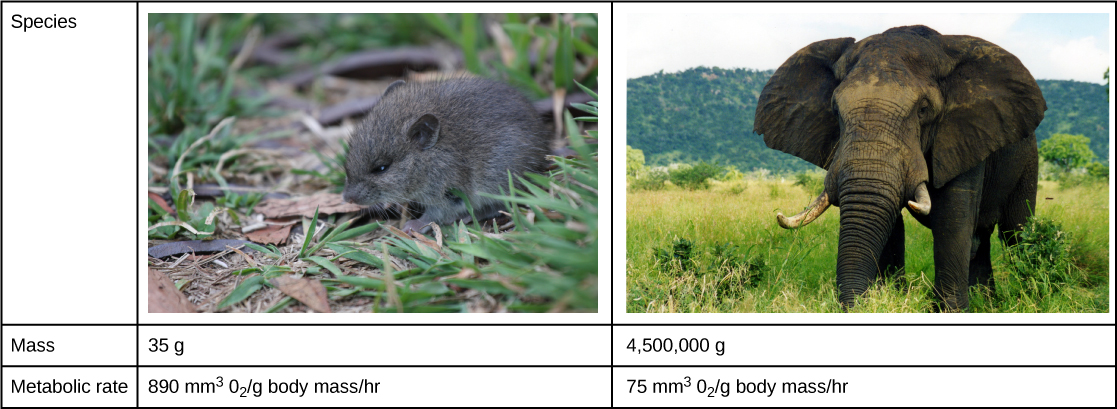

较小的吸热动物的体重表面积大于较大的吸热动物(图\(\PageIndex{3}\)). Therefore, smaller animals lose heat at a faster rate than larger animals and require more energy to maintain a constant internal temperature. This results in a smaller endothermic animal having a higher BMR, per body weight, than a larger endothermic animal.

Energy Requirements Related to Levels of Activity

The more active an animal is, the more energy is needed to maintain that activity, and the higher its BMR or SMR. The average daily rate of energy consumption is about two to four times an animal’s BMR or SMR. Humans are more sedentary than most animals and have an average daily rate of only 1.5 times the BMR. The diet of an endothermic animal is determined by its BMR. For example: the type of grasses, leaves, or shrubs that an herbivore eats affects the number of calories that it takes in. The relative caloric content of herbivore foods, in descending order, is tall grasses > legumes > short grasses > forbs (any broad-leaved plant, not a grass) > subshrubs > annuals/biennials.

Energy Requirements Related to Environment

Animals adapt to extremes of temperature or food availability through torpor. Torpor is a process that leads to a decrease in activity and metabolism and allows animals to survive adverse conditions. Torpor can be used by animals for long periods, such as entering a state of hibernation during the winter months, in which case it enables them to maintain a reduced body temperature. During hibernation, ground squirrels can achieve an abdominal temperature of 0° C (32° F), while a bear’s internal temperature is maintained higher at about 37° C (99° F).

If torpor occurs during the summer months with high temperatures and little water, it is called estivation. Some desert animals use this to survive the harshest months of the year. Torpor can occur on a daily basis; this is seen in bats and hummingbirds. While endothermy is limited in smaller animals by surface to volume ratio, some organisms can be smaller and still be endotherms because they employ daily torpor during the part of the day that is coldest. This allows them to conserve energy during the colder parts of the day, when they consume more energy to maintain their body temperature.

Animal Body Planes and Cavities

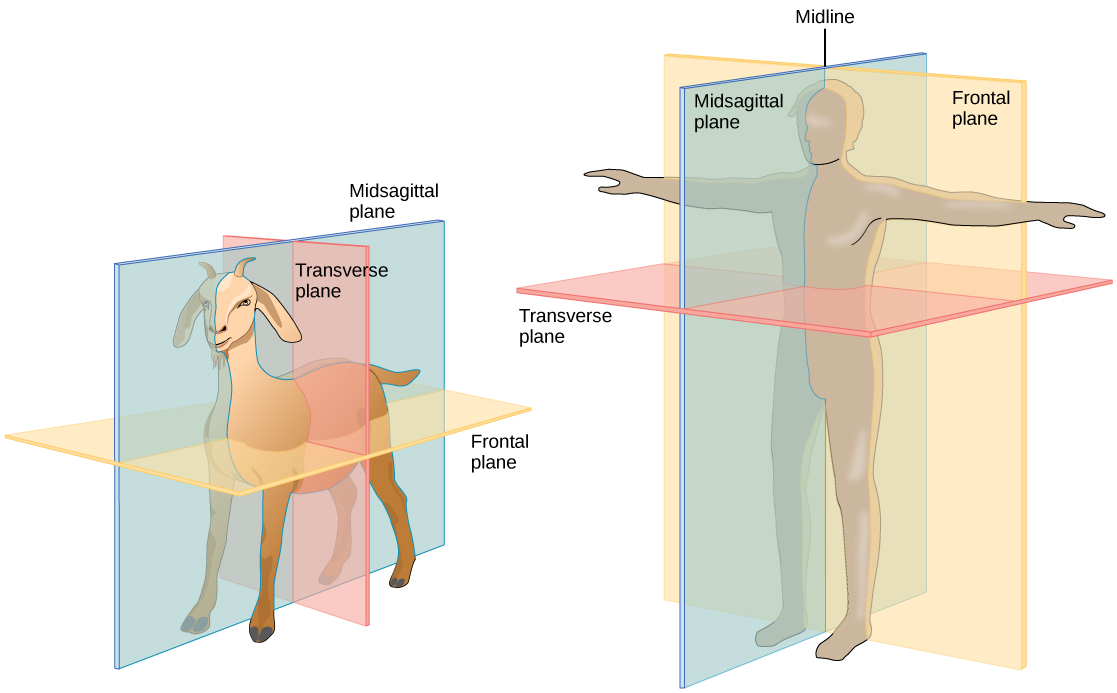

A standing vertebrate animal can be divided by several planes. A sagittal plane divides the body into right and left portions. A midsagittal plane divides the body exactly in the middle, making two equal right and left halves. A frontal plane (also called a coronal plane) separates the front from the back. A transverse plane (or, horizontal plane) divides the animal into upper and lower portions. This is sometimes called a cross section, and, if the transverse cut is at an angle, it is called an oblique plane. Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) illustrates these planes on a goat (a four-legged animal) and a human being.

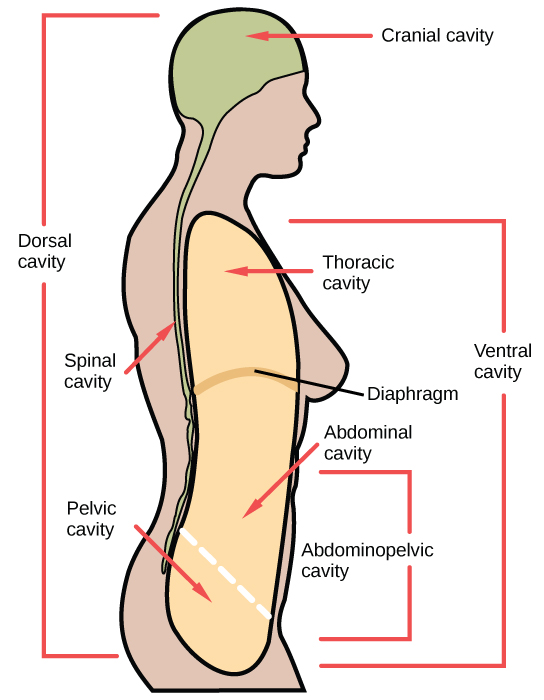

Vertebrate animals have a number of defined body cavities, as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\). Two of these are major cavities that contain smaller cavities within them. The dorsal cavity contains the cranial and the vertebral (or spinal) cavities. The ventral cavity contains the thoracic cavity, which in turn contains the pleural cavity around the lungs and the pericardial cavity, which surrounds the heart. The ventral cavity also contains the abdominopelvic cavity, which can be separated into the abdominal and the pelvic cavities.

Career Connections: Physical Anthropologist

Physical anthropologists study the adaption, variability, and evolution of human beings, plus their living and fossil relatives. They can work in a variety of settings, although most will have an academic appointment at a university, usually in an anthropology department or a biology, genetics, or zoology department.

Non-academic positions are available in the automotive and aerospace industries where the focus is on human size, shape, and anatomy. Research by these professionals might range from studies of how the human body reacts to car crashes to exploring how to make seats more comfortable. Other non-academic positions can be obtained in museums of natural history, anthropology, archaeology, or science and technology. These positions involve educating students from grade school through graduate school. Physical anthropologists serve as education coordinators, collection managers, writers for museum publications, and as administrators. Zoos employ these professionals, especially if they have an expertise in primate biology; they work in collection management and captive breeding programs for endangered species. Forensic science utilizes physical anthropology expertise in identifying human and animal remains, assisting in determining the cause of death, and for expert testimony in trials.

Summary

Animal bodies come in a variety of sizes and shapes. Limits on animal size and shape include impacts to their movement. Diffusion affects their size and development. Bioenergetics describes how animals use and obtain energy in relation to their body size, activity level, and environment.

Glossary

- apodeme

- ingrowth of an animal’s exoskeleton that functions as an attachment site for muscles

- asymmetrical

- describes animals with no axis of symmetry in their body pattern

- basal metabolic rate (BMR)

- metabolic rate at rest in endothermic animals

- dorsal cavity

- body cavity on the posterior or back portion of an animal; includes the cranial and vertebral cavities

- ectotherm

- animal incapable of maintaining a relatively constant internal body temperature

- endotherm

- animal capable of maintaining a relatively constant internal body temperature

- estivation

- torpor in response to extremely high temperatures and low water availability

- frontal (coronal) plane

- plane cutting through an animal separating the individual into front and back portions

- fusiform

- animal body shape that is tubular and tapered at both ends

- hibernation

- torpor over a long period of time, such as a winter

- midsagittal plane

- plane cutting through an animal separating the individual into even right and left sides

- sagittal plane

- plane cutting through an animal separating the individual into right and left sides

- standard metabolic rate (SMR)

- metabolic rate at rest in ectothermic animals

- torpor

- decrease in activity and metabolism that allows an animal to survive adverse conditions

- transverse (horizontal) plane

- plane cutting through an animal separating the individual into upper and lower portions

- ventral cavity

- body cavity on the anterior or front portion of an animal that includes the thoracic cavities and the abdominopelvic cavities