29.4: 爬行动物

- Page ID

- 203161

培养技能

- 描述羊膜生物的主要特征

- 解释 anapsids、synapsids 和 diapsids 之间的区别,并举个例子

- 识别爬行动物的特征

- 讨论爬行动物的进化

羊膜动物(爬行动物、鸟类和哺乳动物)与两栖动物的区别在于它们的地面适应卵,受羊膜保护。 羊膜的进化意味着羊膜的胚胎有了自己的水生环境,从而减少了对水发育的依赖,从而使羊膜能够分支到更干燥的环境中。 这是一项重大发展,使它们与两栖动物区分开来,两栖动物因其无壳卵而仅限于潮湿的环境。 尽管各种羊膜物种的贝壳差异很大,但它们都允许保留水分。 鸟蛋的壳由碳酸钙组成,坚硬但脆弱。 爬行动物蛋的外壳是皮革状的,需要潮湿的环境。 大多数哺乳动物不产卵(单极哺乳动物除外)。 相反,胚胎在母亲体内生长;但是,即使有这种内部妊娠,羊膜仍然存在。

羊膜的特征

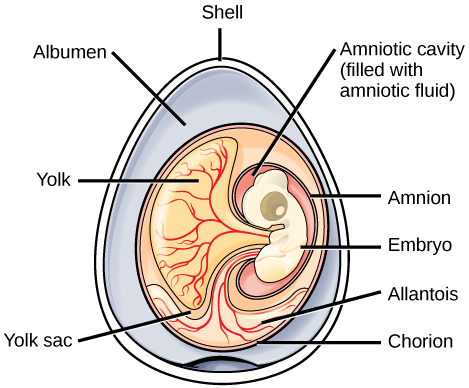

羊膜卵是羊膜动物的关键特征。 在产卵的羊膜动物中,卵壳为发育中的胚胎提供保护,同时具有足够的渗透性,允许二氧化碳和氧气的交换。 白蛋白或蛋清为胚胎提供水分和蛋白质,而较肥的蛋黄是胚胎的能量供应,许多其他动物(例如两栖动物)的卵也是如此。 但是,羊膜卵含有另外三个胚外膜:绒毛膜、羊膜和尿囊膜(图\(\PageIndex{1}\))。 胚外膜是羊膜卵中存在的膜,不是发育中的胚胎身体的一部分。 当内部羊膜环绕胚胎本身时,绒毛膜围绕着胚胎和卵黄囊。 绒毛膜促进胚胎和卵子外部环境之间氧气和二氧化碳的交换。 羊膜保护胚胎免受机械冲击并支持补水。 尿囊储存胚胎产生的含氮废物,还有助于呼吸。 在哺乳动物中,胎盘中存在与卵中胚外膜同源的膜。

艺术连接

以下关于鸡蛋各部分的陈述中哪一项是错误的?

- 尿囊可储存含氮废物并促进呼吸。

- 绒毛膜促进气体交换。

- 蛋黄为成长中的胚胎提供食物。

- 羊膜腔里充满了蛋白。

羊膜生物的其他衍生特征包括由于脂质存在而导致皮肤防水,以及肺部肋骨(肋)通气。

羊膜动物的进化

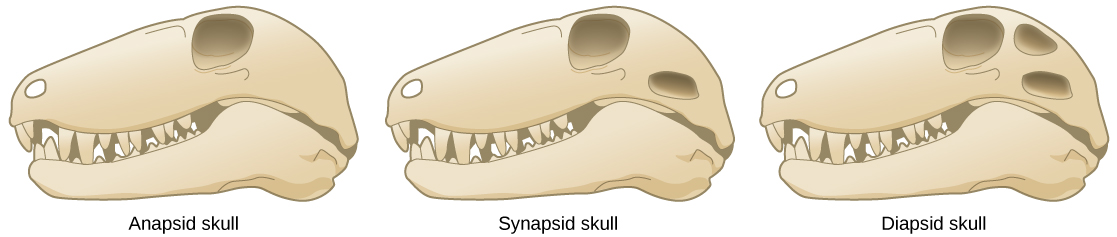

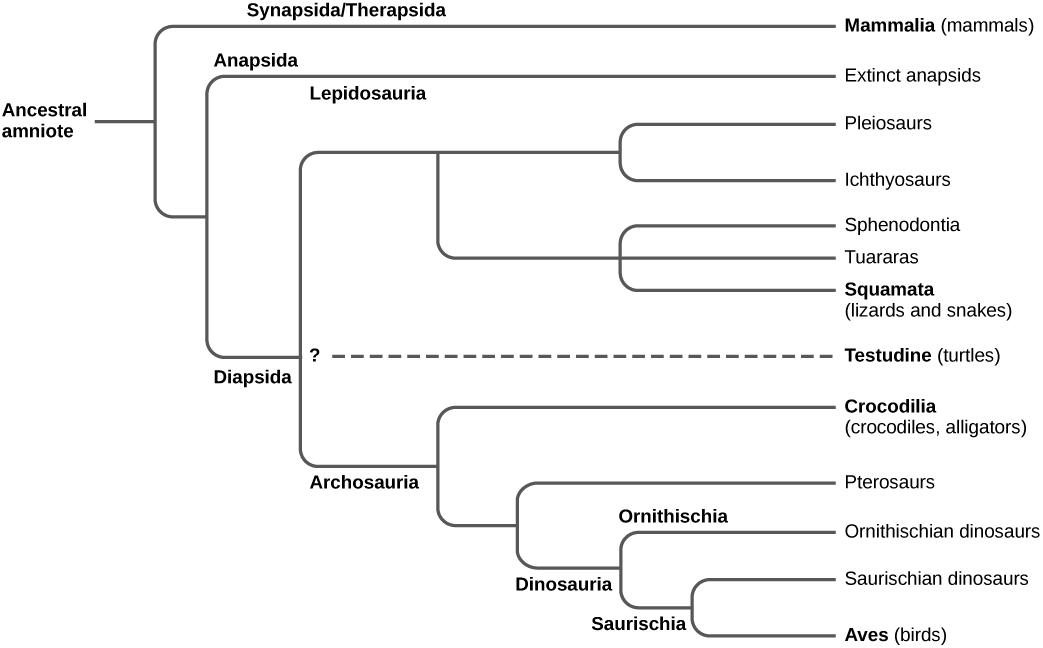

第一批羊膜动物是由大约3.4亿年前的石炭纪时期的两栖动物祖先进化而来的。 在第一批羊膜生物出现后不久,早期的羊膜分裂成两条主线。 最初的分裂分为突触和索罗普西德斯。 Synapsids 包括所有哺乳动物,包括已灭绝的哺乳动物物种。 Synapsids 还包括疗法,它们是哺乳动物进化而来的类似哺乳动物的爬行动物。 Sauropsid s 包括爬行动物和鸟类,可以进一步分为 anapsids 和 diapsids。 synapsids、anapsids 和 diapsids 之间的主要区别在于头骨的结构和每只眼睛后面的 tempory fenestrae 的数量(图\(\PageIndex{2}\))。 T@@ emporal fenestrae 是头骨的眶后开口,允许肌肉膨胀和延长。 Anapsids 没有 tempory fenestrae,synapsids 有一个,diapsids 有两个。 Anapsids 包括已灭绝的生物,根据解剖学,可能包括海龟。 但是,这仍然存在争议,根据分子证据,海龟有时被归类为 diapsids。 diapsids 包括鸟类和所有其他活着和灭绝的爬行动物。

diapsids 分为两组,即中生代时期的 Archosauromorpha(“古蜥蜴形态”)和 Lepidosauromorpha(“鳞状蜥蜴形态”)(图\(\PageIndex{3}\))。 鳞龙包括现代蜥蜴、蛇和 tuataras。 大龙包括现代鳄鱼和短吻鳄,以及已灭绝的翼龙(“有翼蜥蜴”)和恐龙(“可怕的蜥蜴”)。 Clade Dinosauria 包括鸟类,它们是从恐龙的一个分支进化而来的。

艺术连接

Testudines 骑士团的成员有一个类似 anapsid 的头骨,有一个开口。 但是,分子研究表明,海龟是 diapsid 祖先的后代。 为什么会这样?

过去,羊膜动物最常见的分为哺乳动物、爬行动物和鸟类。 但是,鸟类是恐龙的后代,因此这种经典方案导致的群体不是真正的进化枝。 在本次讨论中,我们将把鸟类视为一个与爬行动物截然不同的群体,但有一项谅解,即这并不能完全反映系统发育的历史和关系。

爬行动物的特征

爬行动物是四足动物。 无肢爬行动物(蛇和其他 squamates)有残留的四肢,与 caecilians 一样,它们被归类为四足动物,因为它们是四肢祖先的后代。 爬行动物在陆地上产下被贝壳封闭的卵。 甚至水生爬行动物也会返回陆地产卵。 它们通常通过内部受精进行性繁殖。 有些物种表现出 ovoviviparity,卵在准备孵化之前会留在母亲的体内。 其他物种是胎生的,后代是活着出生的。

允许爬行动物在陆地上生活的关键适应措施之一是发育出鳞片状的皮肤,其中含有蛋白质角蛋白和蜡质脂质,从而减少了皮肤的水分流失。 这种闭塞性皮肤意味着爬行动物不能像两栖动物一样使用皮肤进行呼吸,因此所有爬行动物都用肺呼吸。

爬行动物是外热,它们的主要体热源来自环境。 这与吸热形成鲜明对比,吸热利用新陈代谢产生的热量来调节体温。 除了具有外热作用外,爬行动物还被归类为 poikilotherms,即体温变化而不是保持稳定的动物。 爬行动物具有行为适应能力,可以帮助调节体温,例如在阳光充足的地方晒太阳热身,寻找阴暗的地方或进入地下降温。 外热疗法的优势在于,不需要食物中的新陈代谢能量来加热身体;因此,爬行动物可以依靠类似大小的吸热所需卡路里的大约10%生存。 在寒冷的天气里,一些爬行动物,例如吊袜带蛇 brumate。 Brum ation 与冬眠相似,因为动物会变得不那么活跃,可以长时间不吃东西,但与冬眠的不同之处在于 brumating 爬行动物没有睡着或靠脂肪储备为生。 相反,它们的新陈代谢因低温而减慢,动物非常缓慢。

爬行动物的进化

爬行动物起源于大约3亿年前的石炭纪时期。 已知最古老的羊膜动物之一是 Casineria,它具有两栖动物和爬行动物的特征。 最早的无可争议的爬行动物之一是 Hylonomus。 第一批羊膜动物出现后不久,在二叠纪时期,它们分为三组:synapsids、anapsids 和 diapsids。 二叠纪时期还出现了 diapsid 爬行动物的第二次重大分歧,分为 archosaurs(鳄鱼和恐龙的前身)和 lepidosaurs(蛇和蜥蜴的前身)。 这些群体一直不显眼,直到三叠纪时期,由于二叠纪-三叠纪灭绝期间大体的 anapsids 和 synapsids 的灭绝,大龙成为占主导地位的陆地群体。 大约2.5亿年前,大龙辐射到恐龙和翼龙中。

尽管翼龙有时被错误地称为恐龙,但它们与真正的恐龙截然不同(图\(\PageIndex{4}\))。 翼龙有许多允许飞行的改编作品,包括空心骨头(鸟类还表现出空心骨头,这是趋同进化的案例)。 它们的翅膀是由皮肤膜形成的,这些皮肤膜附着在每只手臂的长无名指上,沿着身体延伸到腿部。

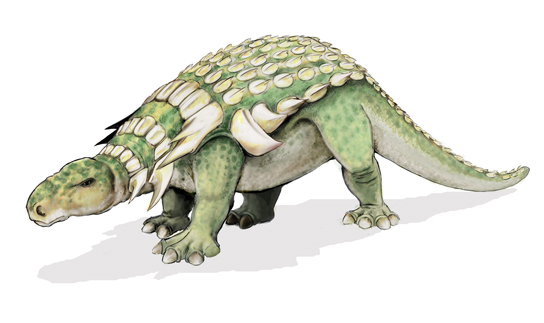

恐龙是一个由陆地爬行动物组成的多样化群体,迄今已发现了1,000多种物种。 古生物学家继续发现新的恐龙物种。 有些恐龙是四足动物(图\(\PageIndex{5}\));其他恐龙是两足动物。 有些是肉食性的,而另一些是草食性的。 恐龙产卵,并发现了许多含有化石卵的巢穴。 目前尚不清楚恐龙是吸热还是外热。 但是,鉴于现代鸟类具有吸热性,作为鸟类祖先的恐龙也可能具有吸热作用。 有一些化石证据表明存在恐龙家长照顾,比较生物学支持这一假设,因为大龙鸟和鳄鱼表现出父母的照顾。

恐龙在中生代占据主导地位,中生代被称为 “爬行动物时代”。 恐龙的统治地位一直持续到白垩纪末期,也就是中生代的最后一个时期。 白垩纪-第三纪灭绝导致中生代大多数大型动物丧生。 鸟类是恐龙主要进化枝之一的唯一活着的后代。

现代爬行动物

Class Reptilia 包括许多不同的物种,这些物种分为四个活进化枝。 这是 25 种 Crocodilia、2 种 Sphenodontia、大约 9,200 个 Squamata 物种和大约 325 个物种的 Testudines。

Crocodilia

鳄鱼(“小蜥蜴”)起源于三叠纪中期,有着独特的血统;现存物种包括短吻鳄、鳄鱼和凯门鳄。 鳄鱼(图\(\PageIndex{6}\)) live throughout the tropics and subtropics of Africa, South America, Southern Florida, Asia, and Australia. They are found in freshwater, saltwater, and brackish habitats, such as rivers and lakes, and spend most of their time in water. Some species are able to move on land due to their semi-erect posture.

Sphenodontia

Sphenodontia (“wedge tooth”) arose in the Mesozoic era and includes only one living genus, Tuatara, comprising two species that are found in New Zealand (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). Tuataras measure up to 80 centimeters and weigh about 1 kilogram. Although quite lizard-like in gross appearance, several unique features of the skull and jaws clearly define them and distinguish the group from the squamates.

Squamata

Squamata (“scaly”) arose in the late Permian, and extant species include lizards and snakes. Both are found on all continents except Antarctica. Lizards and snakes are most closely related to tuataras, both groups having evolved from a lepidosaurian ancestor. Squamata is the largest extant clade of reptiles (Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)). Most lizards differ from snakes by having four limbs, although these have been variously lost or significantly reduced in at least 60 lineages. Snakes lack eyelids and external ears, which are present in lizards. Lizard species range in size from chameleons and geckos, which are a few centimeters in length, to the Komodo dragon, which is about 3 meters in length. Most lizards are carnivorous, but some large species, such as iguanas, are herbivores.

Snakes are thought to have descended from either burrowing lizards or aquatic lizards over 100 million years ago (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)). Snakes comprise about 3,000 species and are found on every continent except Antarctica. They range in size from 10 centimeter-long thread snakes to 10 meter-long pythons and anacondas. All snakes are carnivorous and eat small animals, birds, eggs, fish, and insects. The snake body form is so specialized that, in its general morphology, a “snake is a snake.” Their specializations all point to snakes having evolved to feed on relatively large prey (even though some current species have reversed this trend). Although variations exist, most snakes have a skull that is very flexible, involving eight rotational joints. They also differ from other squamates by having mandibles (lower jaws) without either bony or ligamentous attachment anteriorly. Having this connection via skin and muscle allows for great expansion of the gape and independent motion of the two sides—both advantages in swallowing big items.

Testudines

Turtles are members of the clade Testudines (“having a shell”) (Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)). Turtles are characterized by a bony or cartilaginous shell. The shell consists of the ventral surface called the plastron and the dorsal surface called the carapace, which develops from the ribs. The plastron is made of scutes or plates; the scutes can be used to differentiate species of turtles. The two clades of turtles are most easily recognized by how they retract their necks. The dominant group, which includes all North American species, retracts its neck in a vertical S-curve. Turtles in the less speciose clade retract the neck with a horizontal curve.

Turtles arose approximately 200 million years ago, predating crocodiles, lizards, and snakes. Similar to other reptiles, turtles are ectotherms. They lay eggs on land, although many species live in or near water. None exhibit parental care. Turtles range in size from the speckled padloper tortoise at 8 centimeters (3.1 inches) to the leatherback sea turtle at 200 centimeters (over 6 feet). The term “turtle” is sometimes used to describe only those species of Testudines that live in the sea, with the terms “tortoise” and “terrapin” used to refer to species that live on land and in fresh water, respectively.

Summary

The amniotes are distinguished from amphibians by the presence of a terrestrially adapted egg protected by amniotic membranes. The amniotes include reptiles, birds, and mammals. The early amniotes diverged into two main lines soon after the first amniotes arose. The initial split was into synapsids (mammals) and sauropsids. Sauropsids can be further divided into anapsids (turtles) and diapsids (birds and reptiles). Reptiles are tetrapods either having four limbs or descending from such. Limbless reptiles (snakes) are classified as tetrapods, as they are descended from four-limbed organisms. One of the key adaptations that permitted reptiles to live on land was the development of scaly skin containing the protein keratin, which prevented water loss from the skin. Reptilia includes four living clades: Crocodilia (crocodiles and alligators), Sphenodontia (tuataras), Squamata (lizards and snakes), and Testudines (turtles).

Art Connections

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Which of the following statements about the parts of an egg are false?

- The allantois stores nitrogenous waste and facilitates respiration.

- The chorion facilitates gas exchange.

- The yolk provides food for the growing embryo.

- The amniotic cavity is filled with albumen.

- Answer

-

D

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Members of the order Testudines have an anapsid-like skull with one opening. However, molecular studies indicate that turtles descended from a diapsid ancestor. Why might this be the case?

- Answer

-

The ancestor of modern Testudines may at one time have had a second opening in the skull, but over time this might have been lost.

Glossary

- amniote

- animal that produces a terrestrially adapted egg protected by amniotic membranes

- allantois

- membrane of the egg that stores nitrogenous wastes produced by the embryo; also facilitates respiration

- amnion

- membrane of the egg that protects the embryo from mechanical shock and prevents dehydration

- anapsid

- animal having no temporal fenestrae in the cranium

- archosaur

- modern crocodilian or bird, or an extinct pterosaur or dinosaur

- brumation

- period of much reduced metabolism and torpor that occurs in any ectotherm in cold weather

- Casineria

- one of the oldest known amniotes; had both amphibian and reptilian characteristics

- chorion

- membrane of the egg that surrounds the embryo and yolk sac

- Crocodilia

- crocodiles and alligators

- diapsid

- animal having two temporal fenestrae in the cranium

- Hylonomus

- one of the earliest reptiles

- lepidosaur

- modern lizards, snakes, and tuataras

- sauropsid

- reptile or bird

- Sphenodontia

- clade of tuataras

- Squamata

- clade of lizards and snakes

- synapsid

- mammal having one temporal fenestra

- temporal fenestra

- non-orbital opening in the skull that may allow muscles to expand and lengthen

- Testudines

- order of turtles