9.2: 什么是寿命发展?

- Page ID

- 203393

学习目标

- 定义和区分三个发展领域:身体、认知和心理社会

- 讨论规范的发展方针

- 了解发展中的三个主要问题:连续性和不连续性,一条共同的发展过程或许多独特的发展道路,以及自然与养育

当我看见时,我的心跳了起来

天空中的彩虹:

我现在是男人了

等我变老的时候就这样吧

或者让我死!

孩子是男人的父亲;

我本来希望我的日子过得去

用@@ 天生的虔诚将每个人捆绑在一起。 (华兹华斯,1802 年)

威廉·华兹华斯在这首诗中写道:“孩子是男人的父亲。” 这个看似不协调的说法是什么意思,它与寿命发展有什么关系? 华兹华斯可能会暗示他成年后的身份在很大程度上取决于他在童年时期的经历。 考虑以下问题:你今天的成年人在多大程度上受到你曾经的孩子的影响? 孩子在多大程度上与他长大后成为的成年人有根本的不同?

这些是发展心理学家试图通过研究人类从受孕到童年、青春期、成年和死亡的变化和成长来回答的问题。 他们将发展视为一个终身过程,可以在三个发展领域进行科学研究:身体、认知和社会心理发展。 身体发育涉及身体和大脑、感官、运动技能以及健康和保健的生长和变化。 认知发展涉及学习、注意力、记忆、语言、思维、推理和创造力。 心理社会发展涉及情感、个性和社交关系。 我们在整个章节中都提到了这些领域。

连接概念:发展心理学中的研究方法

你已经了解了心理学家使用的各种研究方法。 发育心理学家使用其中的许多方法来更好地了解个人如何随着时间的推移而发生心理和身体变化。 这些方法包括自然观察、案例研究、调查和实验等。

自然主义观测涉及在自然环境中观察行为。 发育心理学家可能会观察孩子在操场、日托中心或自己家中的行为。 尽管这种研究方法可以让人们了解孩子在自然环境中的行为,但研究人员对表现行为的类型和/或频率几乎没有控制权。

在案例研究中,发育心理学家从一个人那里收集了大量信息,以便更好地了解生命周期中的生理和心理变化。 这种特殊的方法是更好地理解个人的绝佳方法,他们在某种程度上是杰出的,但它特别容易出现研究人员在解释方面的偏见,也很难将结论推广到更多人群。

在将这种研究方法应用于寿命发育研究的一个经典例子中,西格蒙德·弗洛伊德分析了一个名叫 “小汉斯” 的孩子的发育情况(弗洛伊德,1909/1949)。 弗洛伊德的发现为他关于儿童性心理发育的理论提供了依据,你将在本章后面介绍这些理论。 Little Genie是思维与智力章节中讨论的案例研究的主题,它提供了另一个例子,说明心理学家如何通过对单个体的详细研究来审视发展里程碑。 就吉妮而言,她的疏忽和虐待性成长经历导致她无法说话,直到她年纪\(13\)大了才离开那个有害的环境。 当她学会使用语言时,心理学家得以比较她在发育后期的语言习得能力与在婴儿期到幼儿期(Fromkin、Krashen、Curtiss、Rigler 和 Rigler)的典型获得这些技能的不同之处1974 年;柯蒂斯,1981 年)。

调查方法要求个人自我报告有关其思想、经历和信念的重要信息。 这种特殊的方法可以在相对较短的时间内提供大量信息;但是,以这种方式收集的数据的有效性取决于诚实的自我报告,与案例研究中收集的信息的深度相比,数据相对较浅。

实验涉及对无关变量的显著控制和自变量的操纵。 因此,实验研究允许发育心理学家对某些对发育过程很重要的变量做出因果陈述。 由于实验研究必须在受控的环境中进行,因此研究人员必须谨慎对待实验室中观察到的行为是否会转化为个人的自然环境。

在本章的后面部分,您将学习一些实验,在这些实验中,幼儿和幼儿观察场景或动作,以便研究人员可以确定特定年龄的认知能力在哪个年龄段发展。 例如,孩子们可能会观察到一定量的液体从一个短而肥的玻璃杯中倒入一个又高又薄的玻璃杯中。 当实验者向孩子询问发生了什么时,受试者的回答可以帮助心理学家理解孩子在多大年龄开始理解,尽管容器的形状不同,但液体的体积保持不变。

在这三个领域(身体、认知和心理社会)中,还讨论了规范的发展方法。 这种方法问:“什么是正常发育?” 在本\(20^{th}\)世纪初的几十年中,规范心理学家研究了大量不同年龄的儿童,以确定大多数孩子何时在三个领域达到特定发育里程碑的规范(即平均年龄)(Gesell,1933、1939、1940;Gesell & Ilg,1946;Hall,1904)。 尽管孩子的发育速度略有不同,但我们可以使用这些与年龄相关的平均值作为一般指导方针,将孩子与同龄同龄同龄人进行比较,以确定他们应该达到称为发育里程碑的特定规范事件的大致年龄(例如,爬行、散步、写作、穿衣、命名颜色、用句子说话、进入青春期)。

并非所有规范性事件都是普遍性的,这意味着并非所有文化中的所有人都经历过这些事件。 生物学里程碑,例如青春期,往往是普遍的,但社会里程碑,例如孩子开始接受正规教育的年龄,不一定是普遍的;相反,它们影响特定文化中的大多数人(Gesell & Ilg,1946 年)。 例如,在发达国家,儿童在5或6岁左右开始上学,但在发展中国家,比如尼日利亚,如果有的话,儿童通常在高龄入学(Huebler,2005;联合国教育、科学及文化组织 [教科文组织],2013)。

为了更好地理解规范方法,想象一下两个新妈妈,路易莎和金伯利,他们是亲密的朋友,孩子年龄差不多。 路易莎的女儿已经\(14\)几个月大了,金伯利的儿子已经\(12\)几个月大了。 根据规范方法,孩子开始行走的平均年龄为\(12\)几个月。 但是,\(14\)几个月后,路易莎的女儿还没走路。 她告诉金伯利,她担心自己的宝宝可能出了点问题。 金伯利很惊讶,因为她的儿子在他只有\(10\)几个月大的时候就开始走路。 路易莎应该担心吗? 如果女儿\(15\)几个月或\(18\)几个月没走路,她是否应该担心?

发展心理学中的问题

关于人类发展,有许多不同的理论方法。 当我们在本章中对它们进行评估时,请回想一下,发展心理学侧重于人们的变化方式,请记住,我们在本章中介绍的所有方法都涉及变革的问题:变革是平稳还是不平衡(连续还是不连续)? 这种变革模式对每个人来说都是一样的,还是有许多不同的变革模式(一种发展过程与多门课程)? 遗传学和环境如何相互作用以影响发育(自然与养育)?

Is Development Continuous or Discontinuous?

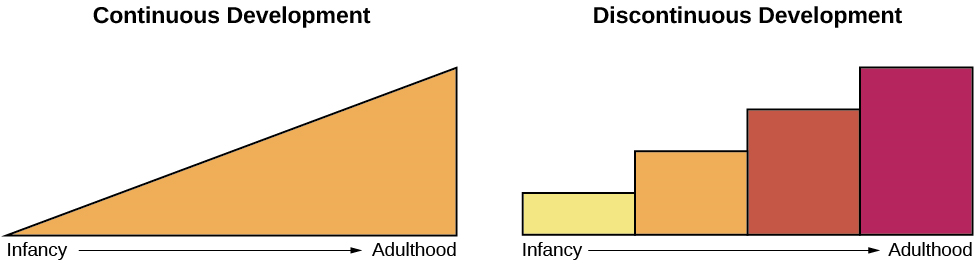

Continuous development views development as a cumulative process, gradually improving on existing skills (See figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). With this type of development, there is gradual change. Consider, for example, a child’s physical growth: adding inches to her height year by year. In contrast, theorists who view development as discontinuous believe that development takes place in unique stages: It occurs at specific times or ages. With this type of development, the change is more sudden, such as an infant’s ability to conceive object permanence.

Is There One Course of Development or Many?

Is development essentially the same, or universal, for all children (i.e., there is one course of development) or does development follow a different course for each child, depending on the child’s specific genetics and environment (i.e., there are many courses of development)? Do people across the world share more similarities or more differences in their development? How much do culture and genetics influence a child’s behavior?

Stage theories hold that the sequence of development is universal. For example, in cross-cultural studies of language development, children from around the world reach language milestones in a similar sequence (Gleitman & Newport, 1995). Infants in all cultures coo before they babble. They begin babbling at about the same age and utter their first word around 12 months old. Yet we live in diverse contexts that have a unique effect on each of us. For example, researchers once believed that motor development follows one course for all children regardless of culture. However, child care practices vary by culture, and different practices have been found to accelerate or inhibit achievement of developmental milestones such as sitting, crawling, and walking (Karasik, Adolph, Tamis-LeMonda, & Bornstein, 2010).

For instance, let’s look at the Aché society in Paraguay. They spend a significant amount of time foraging in forests. While foraging, Aché mothers carry their young children, rarely putting them down in order to protect them from getting hurt in the forest. Consequently, their children walk much later: They walk around \(23-25\0 months old, in comparison to infants in Western cultures who begin to walk around \(12\) months old. However, as Aché children become older, they are allowed more freedom to move about, and by about age \(9\), their motor skills surpass those of U.S. children of the same age: Aché children are able to climb trees up to \(25\) feet tall and use machetes to chop their way through the forest (Kaplan & Dove, 1987). As you can see, our development is influenced by multiple contexts, so the timing of basic motor functions may vary across cultures. However, the functions themselves are present in all societies (See figure below).

How Do Nature and Nurture Influence Development?

Are we who we are because of nature (biology and genetics), or are we who we are because of nurture (our environment and culture)? This longstanding question is known in psychology as the nature versus nurture debate. It seeks to understand how our personalities and traits are the product of our genetic makeup and biological factors, and how they are shaped by our environment, including our parents, peers, and culture. For instance, why do biological children sometimes act like their parents—is it because of genetics or because of early childhood environment and what the child has learned from the parents? What about children who are adopted—are they more like their biological families or more like their adoptive families? And how can siblings from the same family be so different?

We are all born with specific genetic traits inherited from our parents, such as eye color, height, and certain personality traits. Beyond our basic genotype, however, there is a deep interaction between our genes and our environment: Our unique experiences in our environment influence whether and how particular traits are expressed, and at the same time, our genes influence how we interact with our environment (Diamond, 2009; Lobo, 2008). This chapter will show that there is a reciprocal interaction between nature and nurture as they both shape who we become, but the debate continues as to the relative contributions of each.

DIG DEEPER: The Achievement Gap - How Does Socioeconomic Status Affect Development?

The achievement gap refers to the persistent difference in grades, test scores, and graduation rates that exist among students of different ethnicities, races, and—in certain subjects—sexes (Winerman, 2011). Research suggests that these achievement gaps are strongly influenced by differences in socioeconomic factors that exist among the families of these children. While the researchers acknowledge that programs aimed at reducing such socioeconomic discrepancies would likely aid in equalizing the aptitude and performance of children from different backgrounds, they recognize that such large-scale interventions would be difficult to achieve. Therefore, it is recommended that programs aimed at fostering aptitude and achievement among disadvantaged children may be the best option for dealing with issues related to academic achievement gaps (Duncan & Magnuson, 2005).

Low-income children perform significantly more poorly than their middle- and high-income peers on a number of educational variables: They have significantly lower standardized test scores, graduation rates, and college entrance rates, and they have much higher school dropout rates. There have been attempts to correct the achievement gap through state and federal legislation, but what if the problems start before the children even enter school?

Psychologists Betty Hart and Todd Risley (2006) spent their careers looking at early language ability and progression of children in various income levels. In one longitudinal study, they found that although all the parents in the study engaged and interacted with their children, middle- and high-income parents interacted with their children differently than low-income parents. After analyzing \(1,300\) hours of parent-child interactions, the researchers found that middle- and high-income parents talk to their children significantly more, starting when the children are infants. By \(3\) years old, high-income children knew almost double the number of words known by their low-income counterparts, and they had heard an estimated total of \(30\) million more words than the low-income counterparts (Hart & Risley, 2003). And the gaps only become more pronounced. Before entering kindergarten, high-income children score \(60\%\) higher on achievement tests than their low-income peers (Lee & Burkam, 2002).

There are solutions to this problem. At the University of Chicago, experts are working with low-income families, visiting them at their homes, and encouraging them to speak more to their children on a daily and hourly basis. Other experts are designing preschools in which students from diverse economic backgrounds are placed in the same classroom. In this research, low-income children made significant gains in their language development, likely as a result of attending the specialized preschool (Schechter & Byeb, 2007). What other methods or interventions could be used to decrease the achievement gap? What types of activities could be implemented to help the children of your community or a neighboring community?

Summary

Lifespan development explores how we change and grow from conception to death. This field of psychology is studied by developmental psychologists. They view development as a lifelong process that can be studied scientifically across three developmental domains: physical, cognitive development, and psychosocial. There are several theories of development that focus on the following issues: whether development is continuous or discontinuous, whether development follows one course or many, and the relative influence of nature versus nurture on development.

Glossary

- cognitive development

- domain of lifespan development that examines learning, attention, memory, language, thinking, reasoning, and creativity

- continuous development

- view that development is a cumulative process: gradually improving on existing skills

- developmental milestone

- approximate ages at which children reach specific normative events

- discontinuous development

- view that development takes place in unique stages, which happen at specific times or ages

- nature

- genes and biology

- normative approach

- study of development using norms, or average ages, when most children reach specific developmental milestones

- nurture

- environment and culture

- physical development

- domain of lifespan development that examines growth and changes in the body and brain, the senses, motor skills, and health and wellness

- psychosocial development

- domain of lifespan development that examines emotions, personality, and social relationships