9.2: ما هو تطوير العمر؟

- Page ID

- 198012

أهداف التعلم

- تحديد وتمييز مجالات التنمية الثلاثة: الجسدية والمعرفية والنفسية الاجتماعية

- مناقشة النهج المعياري للتنمية

- فهم القضايا الرئيسية الثلاث في التطوير: الاستمرارية والانقطاع، ومسار واحد مشترك للتطوير أو العديد من مسارات التطوير الفريدة، والطبيعة مقابل التنشئة

يقفز قلبي عندما أرى

قوس قزح في السماء:

فهل أنا الآن رجل؛

لذا فليكن عندما أتقدم في العمر

أو دعني أموت!

الطفل هو والد الرجل؛

يمكن أن أتمنى أن تكون أيامي

يرتبط كل منهم بالتقوى الطبيعية. (وردزورث، 1802)

في هذه القصيدة، كتب ويليام وردزورث، «الطفل هو والد الرجل». ماذا تعني هذه العبارة التي تبدو متناقضة، وما علاقة ذلك بتطور العمر؟ قد يشير Wordsworth إلى أن الشخص الذي هو عليه كشخص بالغ يعتمد إلى حد كبير على التجارب التي مر بها في مرحلة الطفولة. ضع في اعتبارك الأسئلة التالية: إلى أي مدى يتأثر الشخص البالغ الذي أنت عليه اليوم بالطفل الذي كنت عليه من قبل؟ إلى أي مدى يختلف الطفل جوهريًا عن الشخص البالغ الذي يكبر عليه؟

هذه هي أنواع الأسئلة التي يحاول علماء النفس التنموي الإجابة عليها، من خلال دراسة كيفية تغير البشر ونموهم من الحمل إلى الطفولة والمراهقة والبلوغ والموت. إنهم ينظرون إلى التنمية على أنها عملية تستمر مدى الحياة ويمكن دراستها علميًا عبر ثلاثة مجالات تنموية - التطور البدني والمعرفي والنفسي الاجتماعي. يشمل التطور البدني النمو والتغيرات في الجسم والدماغ والحواس والمهارات الحركية والصحة والعافية. يشمل التطور المعرفي التعلم والانتباه والذاكرة واللغة والتفكير والتفكير والتفكير والإبداع. يشمل التطور النفسي الاجتماعي العواطف والشخصية والعلاقات الاجتماعية. نشير إلى هذه المجالات في جميع أنحاء الفصل.

ربط المفاهيم: طرق البحث في علم النفس التنموي

لقد تعلمت مجموعة متنوعة من أساليب البحث التي يستخدمها علماء النفس. يستخدم علماء النفس التنموي العديد من هذه الأساليب من أجل فهم أفضل لكيفية تغير الأفراد عقليًا وجسديًا بمرور الوقت. تشمل هذه الأساليب الملاحظات الطبيعية ودراسات الحالة والدراسات الاستقصائية والتجارب وغيرها.

تتضمن الملاحظات الطبيعية مراقبة السلوك في سياقه الطبيعي. قد يلاحظ أخصائي علم النفس التنموي سلوك الأطفال في الملعب أو في مركز الرعاية النهارية أو في منزل الطفل. في حين أن نهج البحث هذا يقدم لمحة عن كيفية تصرف الأطفال في بيئاتهم الطبيعية، إلا أن الباحثين لديهم سيطرة قليلة جدًا على أنواع و/أو ترددات السلوك المعروض.

في دراسة الحالة، يجمع علماء النفس التنموي قدرًا كبيرًا من المعلومات من فرد واحد من أجل فهم التغيرات الجسدية والنفسية بشكل أفضل على مدار العمر. يعد هذا النهج الخاص طريقة ممتازة لفهم الأفراد بشكل أفضل، وهم استثنائيون بطريقة ما، ولكنه عرضة بشكل خاص لتحيز الباحثين في التفسير، ومن الصعب تعميم الاستنتاجات على عدد أكبر من السكان.

في أحد الأمثلة الكلاسيكية لطريقة البحث هذه التي يتم تطبيقها على دراسة تطور العمر، حلل سيغموند فرويد نمو طفل يعرف باسم «ليتل هانز» (فرويد، 1909/1949). ساعدت نتائج فرويد في إثراء نظرياته حول التطور النفسي الجنسي لدى الأطفال، والتي ستتعرف عليها لاحقًا في هذا الفصل. يقدم Little Genie، موضوع دراسة الحالة التي تمت مناقشتها في الفصل الخاص بالتفكير والذكاء، مثالاً آخر على كيفية قيام علماء النفس بفحص المعالم التنموية من خلال البحث التفصيلي على فرد واحد. في حالة جيني، أدت تربيتها المهملة والمسيئة إلى عدم قدرتها على الكلام حتى تم إخراجها من تلك البيئة الضارة في سنها\(13\). عندما تعلمت استخدام اللغة، تمكن علماء النفس من مقارنة كيفية اختلاف قدراتها على اكتساب اللغة عند حدوثها في مرحلة متقدمة من تطورها مقارنة بالاكتساب النموذجي لتلك المهارات خلال سن الطفولة وحتى الطفولة المبكرة (Fromkin, Krashen, Curtiss, Rigler, & Rigler, 1974؛ كورتيس، 1981).

تطلب طريقة المسح من الأفراد الإبلاغ الذاتي عن المعلومات المهمة حول أفكارهم وتجاربهم ومعتقداتهم. يمكن أن توفر هذه الطريقة الخاصة كميات كبيرة من المعلومات في فترات زمنية قصيرة نسبيًا؛ ومع ذلك، تعتمد صحة البيانات التي تم جمعها بهذه الطريقة على الإبلاغ الذاتي الصادق، والبيانات ضحلة نسبيًا عند مقارنتها بعمق المعلومات التي تم جمعها في دراسة الحالة.

تتضمن التجارب تحكمًا كبيرًا في المتغيرات الخارجية ومعالجة المتغير المستقل. على هذا النحو، يسمح البحث التجريبي لعلماء النفس التنموي بالإدلاء ببيانات سببية حول متغيرات معينة مهمة لعملية التطوير. نظرًا لأن البحث التجريبي يجب أن يحدث في بيئة خاضعة للرقابة، يجب على الباحثين توخي الحذر بشأن ما إذا كانت السلوكيات التي تتم ملاحظتها في المختبر تُترجم إلى البيئة الطبيعية للفرد.

ستتعرف لاحقًا في هذا الفصل على العديد من التجارب التي يلاحظ فيها الأطفال الصغار والأطفال الصغار المشاهد أو الأفعال حتى يتمكن الباحثون من تحديد القدرات المعرفية الخاصة بالعمر. على سبيل المثال، قد يلاحظ الأطفال كمية السائل التي يتم سكبها من كوب قصير سمين في كوب طويل ونحيف. عندما يسأل المجربون الأطفال عما حدث، تساعد إجابات الأشخاص علماء النفس على فهم العمر الذي يبدأ فيه الطفل في فهم أن حجم السائل ظل كما هو على الرغم من اختلاف أشكال الحاويات.

عبر هذه المجالات الثلاثة - المادية والمعرفية والنفسية الاجتماعية - تمت مناقشة النهج المعياري للتنمية أيضًا. يسأل هذا النهج: «ما هو التطور الطبيعي؟» في العقود الأولى من\(20^{th}\) القرن، درس علماء النفس المعياريون أعدادًا كبيرة من الأطفال في مختلف الأعمار لتحديد المعايير (أي متوسط الأعمار) عندما يصل معظم الأطفال إلى مراحل نمو محددة في كل من المجالات الثلاثة (Gesell، 1933، 1939، 1940؛ Gesell & Ilg، 1946؛ Hall، 1904). على الرغم من أن الأطفال يتطورون بمعدلات مختلفة قليلاً، يمكننا استخدام هذه المتوسطات المرتبطة بالعمر كإرشادات عامة لمقارنة الأطفال بأقرانهم من نفس العمر لتحديد الأعمار التقريبية التي يجب أن يصلوا إليها إلى أحداث معيارية محددة تسمى المعالم التنموية (على سبيل المثال، الزحف، المشي والكتابة وارتداء الملابس وتسمية الألوان والتحدث بالجمل وبدء البلوغ).

ليست كل الأحداث المعيارية عالمية، مما يعني أنها لا يختبرها جميع الأفراد في جميع الثقافات. تميل المعالم البيولوجية، مثل سن البلوغ، إلى أن تكون عالمية، لكن المعالم الاجتماعية، مثل العمر الذي يبدأ فيه الأطفال التعليم الرسمي، ليست بالضرورة عالمية؛ بدلاً من ذلك، تؤثر على معظم الأفراد في ثقافة معينة (Gesell & Ilg، 1946). على سبيل المثال، يبدأ الأطفال في البلدان المتقدمة المدرسة في سن 5 أو 6 سنوات تقريبًا، ولكن في البلدان النامية، مثل نيجيريا، غالبًا ما يدخل الأطفال المدرسة في سن متقدمة، إن كانوا على الإطلاق (Huebler، 2005؛ منظمة الأمم المتحدة للتربية والعلم والثقافة [اليونسكو]، 2013).

لفهم النهج المعياري بشكل أفضل، تخيل أمتين جديدتين، لويزا وكيمبرلي، وهما صديقتان مقربتان ولديهما أطفال في نفس العمر تقريبًا. تبلغ ابنة لويزا\(14\) شهورًا، وابن كيمبرلي يبلغ من العمر\(12\) شهورًا. وفقًا للنهج المعياري، فإن متوسط العمر الذي يبدأ فيه الطفل في المشي هو\(12\) أشهر. ومع ذلك، في\(14\) الأشهر لا تزال ابنة لويزا لا تمشي. تخبر كيمبرلي أنها قلقة من احتمال حدوث خطأ ما في طفلها. تتفاجأ كيمبرلي لأن ابنها بدأ المشي عندما كان عمره\(10\) شهورًا فقط. هل يجب أن تقلق لويزا? هل يجب أن تشعر بالقلق إذا كانت ابنتها لا تمشي\(15\) لأشهر أو\(18\) أشهر؟

قضايا في علم النفس التنموي

هناك العديد من المناهج النظرية المختلفة فيما يتعلق بالتنمية البشرية. عندما نقوم بتقييمها في هذا الفصل، تذكر أن علم النفس التنموي يركز على كيفية تغير الناس، ونضع في اعتبارك أن جميع الأساليب التي نقدمها في هذا الفصل تتناول أسئلة التغيير: هل التغيير سلس أم غير متساوٍ (مستمر مقابل متقطع)؟ هل هذا النمط من التغيير هو نفسه للجميع، أم أن هناك العديد من أنماط التغيير المختلفة (مسار واحد للتطوير مقابل العديد من الدورات)؟ كيف تتفاعل الوراثة والبيئة للتأثير على التنمية (الطبيعة مقابل التنشئة)؟

Is Development Continuous or Discontinuous?

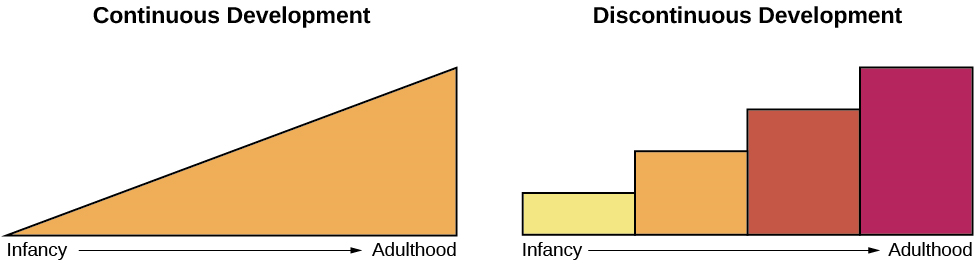

Continuous development views development as a cumulative process, gradually improving on existing skills (See figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). With this type of development, there is gradual change. Consider, for example, a child’s physical growth: adding inches to her height year by year. In contrast, theorists who view development as discontinuous believe that development takes place in unique stages: It occurs at specific times or ages. With this type of development, the change is more sudden, such as an infant’s ability to conceive object permanence.

Is There One Course of Development or Many?

Is development essentially the same, or universal, for all children (i.e., there is one course of development) or does development follow a different course for each child, depending on the child’s specific genetics and environment (i.e., there are many courses of development)? Do people across the world share more similarities or more differences in their development? How much do culture and genetics influence a child’s behavior?

Stage theories hold that the sequence of development is universal. For example, in cross-cultural studies of language development, children from around the world reach language milestones in a similar sequence (Gleitman & Newport, 1995). Infants in all cultures coo before they babble. They begin babbling at about the same age and utter their first word around 12 months old. Yet we live in diverse contexts that have a unique effect on each of us. For example, researchers once believed that motor development follows one course for all children regardless of culture. However, child care practices vary by culture, and different practices have been found to accelerate or inhibit achievement of developmental milestones such as sitting, crawling, and walking (Karasik, Adolph, Tamis-LeMonda, & Bornstein, 2010).

For instance, let’s look at the Aché society in Paraguay. They spend a significant amount of time foraging in forests. While foraging, Aché mothers carry their young children, rarely putting them down in order to protect them from getting hurt in the forest. Consequently, their children walk much later: They walk around \(23-25\0 months old, in comparison to infants in Western cultures who begin to walk around \(12\) months old. However, as Aché children become older, they are allowed more freedom to move about, and by about age \(9\), their motor skills surpass those of U.S. children of the same age: Aché children are able to climb trees up to \(25\) feet tall and use machetes to chop their way through the forest (Kaplan & Dove, 1987). As you can see, our development is influenced by multiple contexts, so the timing of basic motor functions may vary across cultures. However, the functions themselves are present in all societies (See figure below).

How Do Nature and Nurture Influence Development?

Are we who we are because of nature (biology and genetics), or are we who we are because of nurture (our environment and culture)? This longstanding question is known in psychology as the nature versus nurture debate. It seeks to understand how our personalities and traits are the product of our genetic makeup and biological factors, and how they are shaped by our environment, including our parents, peers, and culture. For instance, why do biological children sometimes act like their parents—is it because of genetics or because of early childhood environment and what the child has learned from the parents? What about children who are adopted—are they more like their biological families or more like their adoptive families? And how can siblings from the same family be so different?

We are all born with specific genetic traits inherited from our parents, such as eye color, height, and certain personality traits. Beyond our basic genotype, however, there is a deep interaction between our genes and our environment: Our unique experiences in our environment influence whether and how particular traits are expressed, and at the same time, our genes influence how we interact with our environment (Diamond, 2009; Lobo, 2008). This chapter will show that there is a reciprocal interaction between nature and nurture as they both shape who we become, but the debate continues as to the relative contributions of each.

DIG DEEPER: The Achievement Gap - How Does Socioeconomic Status Affect Development?

The achievement gap refers to the persistent difference in grades, test scores, and graduation rates that exist among students of different ethnicities, races, and—in certain subjects—sexes (Winerman, 2011). Research suggests that these achievement gaps are strongly influenced by differences in socioeconomic factors that exist among the families of these children. While the researchers acknowledge that programs aimed at reducing such socioeconomic discrepancies would likely aid in equalizing the aptitude and performance of children from different backgrounds, they recognize that such large-scale interventions would be difficult to achieve. Therefore, it is recommended that programs aimed at fostering aptitude and achievement among disadvantaged children may be the best option for dealing with issues related to academic achievement gaps (Duncan & Magnuson, 2005).

Low-income children perform significantly more poorly than their middle- and high-income peers on a number of educational variables: They have significantly lower standardized test scores, graduation rates, and college entrance rates, and they have much higher school dropout rates. There have been attempts to correct the achievement gap through state and federal legislation, but what if the problems start before the children even enter school?

Psychologists Betty Hart and Todd Risley (2006) spent their careers looking at early language ability and progression of children in various income levels. In one longitudinal study, they found that although all the parents in the study engaged and interacted with their children, middle- and high-income parents interacted with their children differently than low-income parents. After analyzing \(1,300\) hours of parent-child interactions, the researchers found that middle- and high-income parents talk to their children significantly more, starting when the children are infants. By \(3\) years old, high-income children knew almost double the number of words known by their low-income counterparts, and they had heard an estimated total of \(30\) million more words than the low-income counterparts (Hart & Risley, 2003). And the gaps only become more pronounced. Before entering kindergarten, high-income children score \(60\%\) higher on achievement tests than their low-income peers (Lee & Burkam, 2002).

There are solutions to this problem. At the University of Chicago, experts are working with low-income families, visiting them at their homes, and encouraging them to speak more to their children on a daily and hourly basis. Other experts are designing preschools in which students from diverse economic backgrounds are placed in the same classroom. In this research, low-income children made significant gains in their language development, likely as a result of attending the specialized preschool (Schechter & Byeb, 2007). What other methods or interventions could be used to decrease the achievement gap? What types of activities could be implemented to help the children of your community or a neighboring community?

Summary

Lifespan development explores how we change and grow from conception to death. This field of psychology is studied by developmental psychologists. They view development as a lifelong process that can be studied scientifically across three developmental domains: physical, cognitive development, and psychosocial. There are several theories of development that focus on the following issues: whether development is continuous or discontinuous, whether development follows one course or many, and the relative influence of nature versus nurture on development.

Glossary

- cognitive development

- domain of lifespan development that examines learning, attention, memory, language, thinking, reasoning, and creativity

- continuous development

- view that development is a cumulative process: gradually improving on existing skills

- developmental milestone

- approximate ages at which children reach specific normative events

- discontinuous development

- view that development takes place in unique stages, which happen at specific times or ages

- nature

- genes and biology

- normative approach

- study of development using norms, or average ages, when most children reach specific developmental milestones

- nurture

- environment and culture

- physical development

- domain of lifespan development that examines growth and changes in the body and brain, the senses, motor skills, and health and wellness

- psychosocial development

- domain of lifespan development that examines emotions, personality, and social relationships