10.3: Controle do ciclo celular

- Page ID

- 182169

Habilidades para desenvolver

- Entenda como o ciclo celular é controlado por mecanismos internos e externos à célula

- Explique como os três pontos de verificação de controle interno ocorrem no final do G 1, na transição G 2/M e durante a metáfase

- Descreva as moléculas que controlam o ciclo celular por meio da regulação positiva e negativa

A duração do ciclo celular é altamente variável, mesmo dentro das células de um único organismo. Em humanos, a frequência de renovação celular varia de algumas horas no início do desenvolvimento embrionário, a uma média de dois a cinco dias para células epiteliais e a uma vida humana inteira passada em G 0 por células especializadas, como neurônios corticais ou células musculares cardíacas. Também há variação no tempo que uma célula passa em cada fase do ciclo celular. Quando células de mamíferos de divisão rápida são cultivadas em cultura (fora do corpo em condições ideais de crescimento), a duração do ciclo é de cerca de 24 horas. Em células humanas que se dividem rapidamente com um ciclo celular de 24 horas, a fase G 1 dura aproximadamente nove horas, a fase S dura 10 horas, a fase G 2 dura cerca de quatro horas e meia e a fase M dura aproximadamente meia hora. Nos primeiros embriões de moscas-das-frutas, o ciclo celular é concluído em cerca de oito minutos. O tempo dos eventos no ciclo celular é controlado por mecanismos internos e externos à célula.

Regulação do ciclo celular por eventos externos

Tanto o início quanto a inibição da divisão celular são desencadeados por eventos externos à célula quando ela está prestes a iniciar o processo de replicação. Um evento pode ser tão simples quanto a morte de uma célula próxima ou tão abrangente quanto a liberação de hormônios promotores de crescimento, como o hormônio do crescimento humano (HGH). A falta de HGH pode inibir a divisão celular, resultando em nanismo, enquanto que o excesso de HGH pode resultar em gigantismo. A aglomeração de células também pode inibir a divisão celular. Outro fator que pode iniciar a divisão celular é o tamanho da célula; à medida que a célula cresce, ela se torna ineficiente devido à diminuição da relação entre superfície e volume. A solução para esse problema é dividir.

Seja qual for a fonte da mensagem, a célula recebe o sinal, e uma série de eventos dentro da célula permite que ela entre em interfase. Avançando a partir desse ponto de iniciação, todos os parâmetros necessários durante cada fase do ciclo celular devem ser atendidos ou o ciclo não poderá progredir.

Regulamentação em postos de controle internos

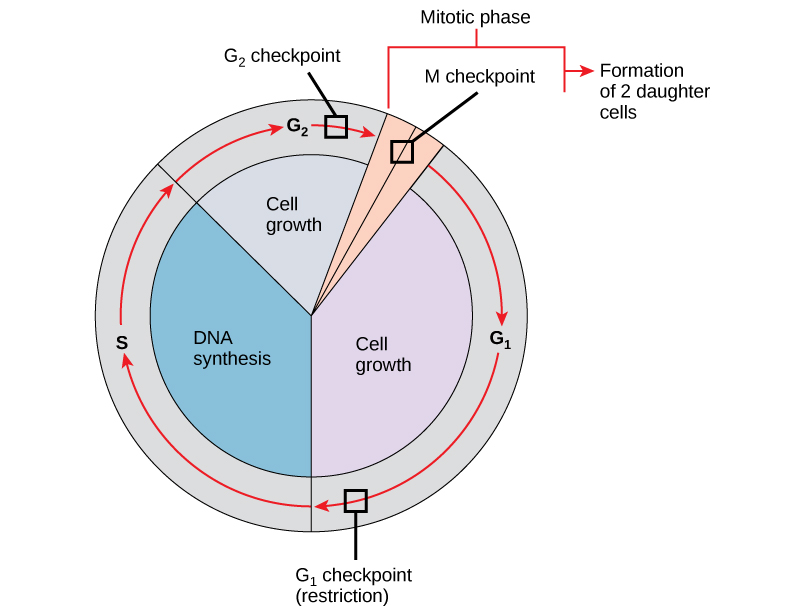

É essencial que as células-filhas produzidas sejam duplicatas exatas da célula-mãe. Erros na duplicação ou distribuição dos cromossomos levam a mutações que podem ser transmitidas para cada nova célula produzida a partir de uma célula anormal. Para evitar que uma célula comprometida continue a se dividir, existem mecanismos de controle interno que operam em três pontos principais de verificação do ciclo celular. Um ponto de verificação é um dos vários pontos do ciclo celular eucariótico em que a progressão de uma célula para o próximo estágio do ciclo pode ser interrompida até que as condições sejam favoráveis. Esses pontos de verificação ocorrem perto do final do G 1, na transição G 2/M e durante a metáfase (Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\)).

O ponto de verificação do G 1

O ponto de verificação G 1 determina se todas as condições são favoráveis para que a divisão celular continue. O ponto de verificação G 1, também chamado de ponto de restrição (na levedura), é um ponto no qual a célula se compromete irreversivelmente com o processo de divisão celular. Influências externas, como fatores de crescimento, desempenham um grande papel no transporte da célula para além do ponto de verificação G1. Além das reservas e do tamanho da célula adequados, há uma verificação de danos ao DNA genômico no ponto de verificação do G 1. Uma célula que não atenda a todos os requisitos não poderá progredir para a fase S. A célula pode interromper o ciclo e tentar remediar a condição problemática, ou a célula pode avançar para G 0 e aguardar novos sinais quando as condições melhorarem.

O ponto de verificação do G 2

O ponto de verificação G 2 impede a entrada na fase mitótica se certas condições não forem atendidas. Como no ponto de verificação do G 1, o tamanho da célula e as reservas de proteína são avaliados. No entanto, o papel mais importante do ponto de verificação do G 2 é garantir que todos os cromossomos tenham sido replicados e que o DNA replicado não seja danificado. Se os mecanismos do ponto de verificação detectarem problemas com o DNA, o ciclo celular é interrompido e a célula tenta completar a replicação do DNA ou reparar o DNA danificado.

O ponto de verificação M

O ponto de verificação M ocorre próximo ao final do estágio de metáfase da cariocinese. O ponto de verificação M também é conhecido como ponto de verificação do fuso, porque determina se todas as cromátides irmãs estão corretamente conectadas aos microtúbulos do fuso. Como a separação das cromátides irmãs durante a anáfase é uma etapa irreversível, o ciclo não prosseguirá até que os cinetócoros de cada par de cromátides irmãs estejam firmemente ancorados em pelo menos duas fibras fusiformes provenientes de pólos opostos da célula.

Link para o aprendizado

Veja o que ocorre nos pontos de verificação G 1, G 2 e M visitando este site para ver uma animação do ciclo celular.

Moléculas reguladoras do ciclo celular

Além dos pontos de verificação controlados internamente, existem dois grupos de moléculas intracelulares que regulam o ciclo celular. Essas moléculas reguladoras promovem o progresso da célula para a próxima fase (regulação positiva) ou interrompem o ciclo (regulação negativa). As moléculas reguladoras podem agir individualmente ou influenciar a atividade ou a produção de outras proteínas reguladoras. Portanto, a falha de um único regulador pode quase não ter efeito no ciclo celular, especialmente se mais de um mecanismo controlar o mesmo evento. Por outro lado, o efeito de um regulador deficiente ou não funcional pode ser amplo e possivelmente fatal para a célula se vários processos forem afetados.

Regulação positiva do ciclo celular

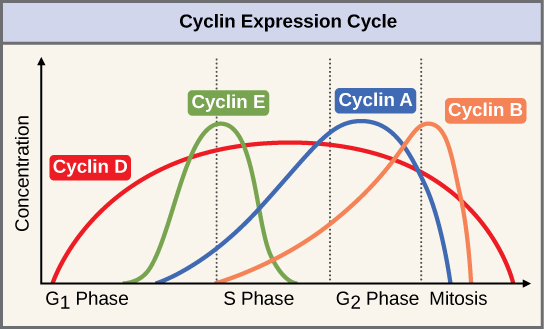

Dois grupos de proteínas, chamados ciclinas e quinases dependentes de ciclina (Cdks), são responsáveis pelo progresso da célula através dos vários pontos de verificação. Os níveis das quatro proteínas ciclina flutuam ao longo do ciclo celular em um padrão previsível (Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\)). Increases in the concentration of cyclin proteins are triggered by both external and internal signals. After the cell moves to the next stage of the cell cycle, the cyclins that were active in the previous stage are degraded.

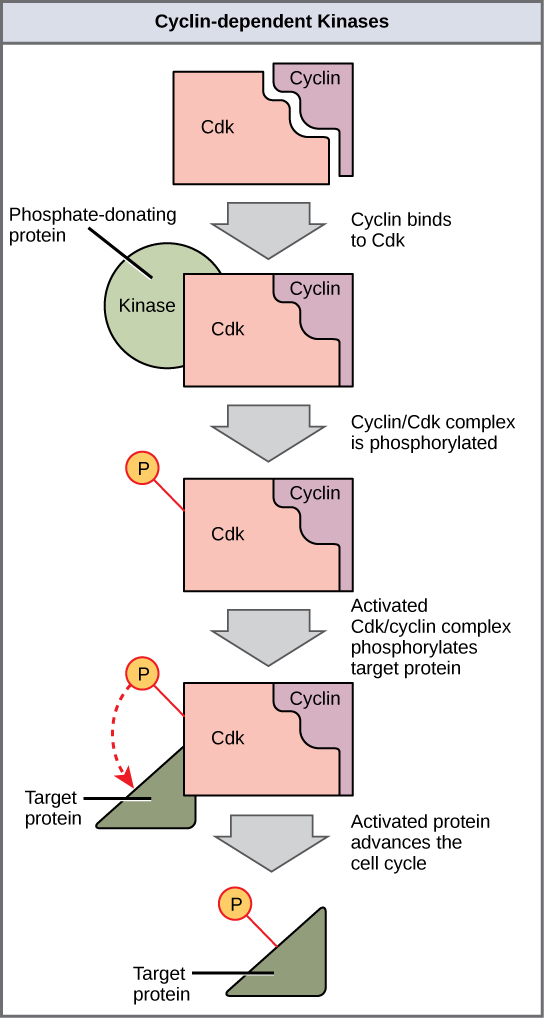

Cyclins regulate the cell cycle only when they are tightly bound to Cdks. To be fully active, the Cdk/cyclin complex must also be phosphorylated in specific locations. Like all kinases, Cdks are enzymes (kinases) that phosphorylate other proteins. Phosphorylation activates the protein by changing its shape. The proteins phosphorylated by Cdks are involved in advancing the cell to the next phase. (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). The levels of Cdk proteins are relatively stable throughout the cell cycle; however, the concentrations of cyclin fluctuate and determine when Cdk/cyclin complexes form. The different cyclins and Cdks bind at specific points in the cell cycle and thus regulate different checkpoints.

Since the cyclic fluctuations of cyclin levels are based on the timing of the cell cycle and not on specific events, regulation of the cell cycle usually occurs by either the Cdk molecules alone or the Cdk/cyclin complexes. Without a specific concentration of fully activated cyclin/Cdk complexes, the cell cycle cannot proceed through the checkpoints.

Although the cyclins are the main regulatory molecules that determine the forward momentum of the cell cycle, there are several other mechanisms that fine-tune the progress of the cycle with negative, rather than positive, effects. These mechanisms essentially block the progression of the cell cycle until problematic conditions are resolved. Molecules that prevent the full activation of Cdks are called Cdk inhibitors. Many of these inhibitor molecules directly or indirectly monitor a particular cell cycle event. The block placed on Cdks by inhibitor molecules will not be removed until the specific event that the inhibitor monitors is completed.

Negative Regulation of the Cell Cycle

The second group of cell cycle regulatory molecules are negative regulators. Negative regulators halt the cell cycle. Remember that in positive regulation, active molecules cause the cycle to progress.

The best understood negative regulatory molecules are retinoblastoma protein (Rb), p53, and p21. Retinoblastoma proteins are a group of tumor-suppressor proteins common in many cells. The 53 and 21 designations refer to the functional molecular masses of the proteins (p) in kilodaltons. Much of what is known about cell cycle regulation comes from research conducted with cells that have lost regulatory control. All three of these regulatory proteins were discovered to be damaged or non-functional in cells that had begun to replicate uncontrollably (became cancerous). In each case, the main cause of the unchecked progress through the cell cycle was a faulty copy of the regulatory protein.

Rb, p53, and p21 act primarily at the G1 checkpoint. p53 is a multi-functional protein that has a major impact on the commitment of a cell to division because it acts when there is damaged DNA in cells that are undergoing the preparatory processes during G1. If damaged DNA is detected, p53 halts the cell cycle and recruits enzymes to repair the DNA. If the DNA cannot be repaired, p53 can trigger apoptosis, or cell suicide, to prevent the duplication of damaged chromosomes. As p53 levels rise, the production of p21 is triggered. p21 enforces the halt in the cycle dictated by p53 by binding to and inhibiting the activity of the Cdk/cyclin complexes. As a cell is exposed to more stress, higher levels of p53 and p21 accumulate, making it less likely that the cell will move into the S phase.

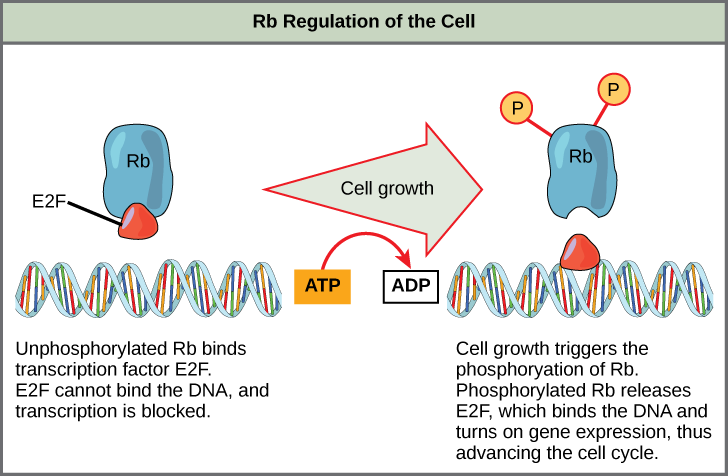

Rb exerts its regulatory influence on other positive regulator proteins. Chiefly, Rb monitors cell size. In the active, dephosphorylated state, Rb binds to proteins called transcription factors, most commonly, E2F (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). Transcription factors “turn on” specific genes, allowing the production of proteins encoded by that gene. When Rb is bound to E2F, production of proteins necessary for the G1/S transition is blocked. As the cell increases in size, Rb is slowly phosphorylated until it becomes inactivated. Rb releases E2F, which can now turn on the gene that produces the transition protein, and this particular block is removed. For the cell to move past each of the checkpoints, all positive regulators must be “turned on,” and all negative regulators must be “turned off.”

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Rb and other proteins that negatively regulate the cell cycle are sometimes called tumor suppressors. Why do you think the name tumor suppressor might be appropriate for these proteins?

- Answer

-

Rb and other negative regulatory proteins control cell division and therefore prevent the formation of tumors. Mutations that prevent these proteins from carrying out their function can result in cancer.

Summary

Each step of the cell cycle is monitored by internal controls called checkpoints. There are three major checkpoints in the cell cycle: one near the end of G1, a second at the G2/M transition, and the third during metaphase. Positive regulator molecules allow the cell cycle to advance to the next stage. Negative regulator molecules monitor cellular conditions and can halt the cycle until specific requirements are met.

Glossary

- cell cycle checkpoint

- mechanism that monitors the preparedness of a eukaryotic cell to advance through the various cell cycle stages

- cyclin

- one of a group of proteins that act in conjunction with cyclin-dependent kinases to help regulate the cell cycle by phosphorylating key proteins; the concentrations of cyclins fluctuate throughout the cell cycle

- cyclin-dependent kinase

- one of a group of protein kinases that helps to regulate the cell cycle when bound to cyclin; it functions to phosphorylate other proteins that are either activated or inactivated by phosphorylation

- p21

- cell cycle regulatory protein that inhibits the cell cycle; its levels are controlled by p53

- p53

- cell cycle regulatory protein that regulates cell growth and monitors DNA damage; it halts the progression of the cell cycle in cases of DNA damage and may induce apoptosis

- retinoblastoma protein (Rb)

- regulatory molecule that exhibits negative effects on the cell cycle by interacting with a transcription factor (E2F)