8.2 : Comment fonctionne la mémoire

- Page ID

- 190339

Objectifs d'apprentissage

- Discutez des trois fonctions de base de la mémoire

- Décrire les trois étapes du stockage en mémoire

- Décrire et distinguer la mémoire procédurale et déclarative et la mémoire sémantique et épisodique

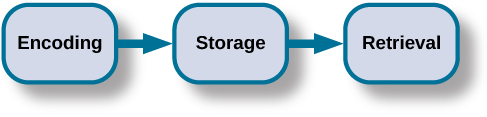

La mémoire est un système de traitement de l'information ; c'est pourquoi nous la comparons souvent à un ordinateur. La mémoire est l'ensemble des processus utilisés pour coder, stocker et récupérer des informations sur différentes périodes.

Encodage

Nous recevons des informations dans notre cerveau par le biais d'un processus appelé encodage, qui est l'entrée d'informations dans le système de mémoire. Une fois que nous recevons des informations sensorielles de l'environnement, notre cerveau les étiquette ou les code. Nous organisons les informations avec d'autres informations similaires et relions de nouveaux concepts à des concepts existants. L'encodage des informations se fait par le biais d'un traitement automatique et d'un

Si quelqu'un vous demande ce que vous avez mangé pour le déjeuner aujourd'hui, vous vous souviendrez probablement assez facilement de cette information. C'est ce que l'on appelle le traitement automatique ou l'encodage de détails tels que le temps, l'espace, la fréquence et la signification des mots. Le traitement automatique est généralement effectué sans aucune prise de conscience consciente. Le fait de vous souvenir de la dernière fois que vous avez étudié pour un test est un autre exemple de traitement automatique. Mais qu'en est-il du matériel de test que vous avez étudié ? Le codage de ces informations a probablement demandé beaucoup de travail et d'attention de votre part. C'est ce que l'on appelle un traitement laborieux.

Quels sont les moyens les plus efficaces de s'assurer que les souvenirs importants sont bien codés ? Même une phrase simple est plus facile à retenir lorsqu'elle a du sens (Anderson, 1984). Lisez les phrases suivantes (Bransford et McCarrell, 1974), puis détournez le regard et comptez à rebours de\(30\) trois à zéro, puis essayez de noter les phrases (pas de retour sur cette page !).

- Les notes étaient aigres car les coutures se fendaient.

- Le voyage n'a pas été retardé car la bouteille s'est brisée.

- La botte de foin était importante parce que le tissu s'est déchiré.

Vous êtes-vous bien débrouillé ? À elles seules, les déclarations que vous avez écrites étaient très probablement confuses et difficiles à mémoriser. Maintenant, essayez de les écrire à nouveau en utilisant les instructions suivantes : cornemuse, baptême de bateau et parachutiste. Comptez ensuite à rebours\(40\) par quatre, puis vérifiez vous-même si vous vous êtes bien souvenu des phrases cette fois. Vous pouvez voir que les phrases sont désormais beaucoup plus mémorables car chacune des phrases a été placée dans son contexte. Le matériel est bien mieux codé lorsque vous le donnez du sens.

Il existe trois types de codage. L'encodage des mots et de leur signification est connu sous le nom de codage sémantique. Cela a été démontré pour la première fois par William Bousfield (1935) lors d'une expérience au cours de laquelle il a demandé aux gens de mémoriser des mots. Les\(60\) mots étaient en fait divisés en 4 catégories de sens, bien que les participants ne le savaient pas car les mots étaient présentés de manière aléatoire. Lorsqu'on leur a demandé de se souvenir des mots, ils ont eu tendance à les classer par catégories, ce qui montre qu'ils prêtaient attention à la signification des mots au fur et à mesure qu'ils les apprenaient.

L'encodage visuel est l'encodage des images, et le codage acoustique est le codage des sons, des mots en particulier. Pour voir comment fonctionne l'encodage visuel, lisez cette liste de mots : voiture, niveau, chien, vérité, livre, valeur. Si on vous demandait plus tard de vous souvenir des mots de cette liste, lesquels pensez-vous que vous vous souviendrez le plus probablement ? Vous auriez probablement plus de mal à vous souvenir des mots voiture, chien et livre, et plus difficile à vous souvenir des mots niveau, vérité et valeur. Pourquoi est-ce ainsi ? Parce que vous pouvez vous souvenir d'images (images mentales) plus facilement que des mots seuls. Lorsque vous lisez les mots voiture, chien et livre, vous avez créé des images de ces choses dans votre esprit. Ce sont des mots concrets très imagés. D'un autre côté, les mots abstraits tels que niveau, vérité et valeur sont des mots peu imagés. Les mots à haute imagerie sont codés à la fois visuellement et sémantiquement (Paivio, 1986), renforçant ainsi la mémoire.

Passons maintenant à l'encodage acoustique. Vous conduisez votre voiture et une chanson passe à la radio que vous n'avez pas entendue\(10\) depuis au moins des années, mais vous chantez en vous remémorant chaque mot. Aux États-Unis, les enfants apprennent souvent l'alphabet par le chant, et ils apprennent le nombre de jours de chaque mois à l'aide de rimes : « Trente jours, c'est septembre/avril, juin et novembre ; /Tous les autres en ont trente et un, /Sauf février, avec vingt-huit jours clairs, /Et vingt-neuf à chaque saut année. » Ces leçons sont faciles à retenir grâce à l'encodage acoustique. Nous encodons les sons émis par les mots. C'est l'une des raisons pour lesquelles une grande partie de ce que nous enseignons aux jeunes enfants se fait par le biais de chansons, de rimes et de rythmes.

Lequel des trois types d'encodage vous procurerait la meilleure mémoire d'informations verbales selon vous ? Il y a quelques années, les psychologues Fergus Craik et Endel Tulving (1975) ont mené une série d'expériences pour le découvrir. Les participants ont reçu des mots et des questions à leur sujet. Les questions demandaient aux participants de traiter les mots à l'un des trois niveaux. Les questions relatives au traitement visuel comprenaient des questions telles que l'interrogation des participants sur la police des lettres. Les questions de traitement acoustique ont interrogé les participants sur le son ou les rimes des mots, et les questions de traitement sémantique ont interrogé les participants sur la signification des mots. Une fois que les mots et les questions ont été présentés aux participants, on leur a confié une tâche de rappel ou de reconnaissance inattendue.

Les mots codés sémantiquement étaient mieux mémorisés que ceux codés visuellement ou acoustiquement. Le codage sémantique implique un niveau de traitement plus profond que le codage visuel ou acoustique moins profond. Craik et Tulving ont conclu que le codage sémantique est le meilleur moyen de traiter les informations verbales, en particulier si nous appliquons ce que l'on appelle l'effet d'autoréférence. L'effet d'autoréférence est la tendance d'une personne à avoir une meilleure mémoire pour les informations qui se rapportent à elle-même que pour les informations qui ont moins d'importance personnelle (Rogers, Kuiper et Kirker, 1977). L'encodage sémantique pourrait-il vous être utile lorsque vous essayez de mémoriser les concepts de ce chapitre ?

Storage

Once the information has been encoded, we have to somehow have to retain it. Our brains take the encoded information and place it in storage. Storage is the creation of a permanent record of information.

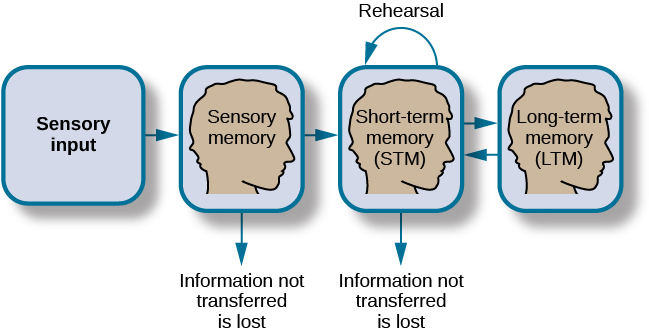

In order for a memory to go into storage (i.e., long-term memory), it has to pass through three distinct stages: Sensory Memory, Short-Term Memory, and finally Long-Term Memory. These stages were first proposed by Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin (1968). Their model of human memory, called Atkinson-Shiffrin (A-S), is based on the belief that we process memories in the same way that a computer processes information.

But A-S is just one model of memory. Others, such as Baddeley and Hitch (1974), have proposed a model where short-term memory itself has different forms. In this model, storing memories in short-term memory is like opening different files on a computer and adding information. The type of short-term memory (or computer file) depends on the type of information received. There are memories in visual-spatial form, as well as memories of spoken or written material, and they are stored in three short-term systems: a visuospatial sketchpad, an episodic buffer, and a phonological loop. According to Baddeley and Hitch, a central executive part of memory supervises or controls the flow of information to and from the three short-term systems.

Sensory Memory

In the Atkinson-Shiffrin model, stimuli from the environment are processed first in sensory memory: storage of brief sensory events, such as sights, sounds, and tastes. It is very brief storage—up to a couple of seconds. We are constantly bombarded with sensory information. We cannot absorb all of it, or even most of it. And most of it has no impact on our lives. For example, what was your professor wearing the last class period? As long as the professor was dressed appropriately, it does not really matter what she was wearing. Sensory information about sights, sounds, smells, and even textures, which we do not view as valuable information, we discard. If we view something as valuable, the information will move into our short-term memory system.

One study of sensory memory researched the significance of valuable information on short-term memory storage. J. R. Stroop discovered a memory phenomenon in the 1930s: you will name a color more easily if it appears printed in that color, which is called the Stroop effect. In other words, the word “red” will be named more quickly, regardless of the color the word appears in, than any word that is colored red. Try an experiment: name the colors of the words you are given in Figure. Do not read the words, but say the color the word is printed in. For example, upon seeing the word “yellow” in green print, you should say “green,” not “yellow.” This experiment is fun, but it’s not as easy as it seems.

Short-Term Memory

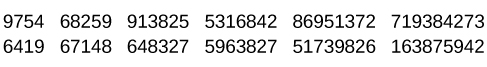

Short-term memory (STM) is a temporary storage system that processes incoming sensory memory; sometimes it is called working memory. Short-term memory takes information from sensory memory and sometimes connects that memory to something already in long-term memory. Short-term memory storage lasts about \(20\) seconds. George Miller (1956), in his research on the capacity of memory, found that most people can retain about \(7\) items in STM. Some remember \(5\), some \(9\), so he called the capacity of STM \(7\) plus or minus \(2\).

Think of short-term memory as the information you have displayed on your computer screen—a document, a spreadsheet, or a web page. Then, information in short-term memory goes to long-term memory (you save it to your hard drive), or it is discarded (you delete a document or close a web browser). This step of rehearsal, the conscious repetition of information to be remembered, to move STM into long-term memory is called memory consolidation.

You may find yourself asking, “How much information can our memory handle at once?” To explore the capacity and duration of your short-term memory, have a partner read the strings of random numbers out loud to you, beginning each string by saying, “Ready?” and ending each by saying, “Recall,” at which point you should try to write down the string of numbers from memory.

Note the longest string at which you got the series correct. For most people, this will be close to \(7\), Miller’s famous \(7\) plus or minus \(2\). Recall is somewhat better for random numbers than for random letters (Jacobs, 1887), and also often slightly better for information we hear (acoustic encoding) rather than see (visual encoding) (Anderson, 1969).

Long-term Memory

Long-term memory (LTM) is the continuous storage of information. Unlike short-term memory, the storage capacity of LTM has no limits. It encompasses all the things you can remember that happened more than just a few minutes ago to all of the things that you can remember that happened days, weeks, and years ago. In keeping with the computer analogy, the information in your LTM would be like the information you have saved on the hard drive. It isn’t there on your desktop (your short-term memory), but you can pull up this information when you want it, at least most of the time. Not all long-term memories are strong memories. Some memories can only be recalled through prompts. For example, you might easily recall a fact— “What is the capital of the United States?”—or a procedure—“How do you ride a bike?”—but you might struggle to recall the name of the restaurant you had dinner when you were on vacation in France last summer. A prompt, such as that the restaurant was named after its owner, who spoke to you about your shared interest in soccer, may help you recall the name of the restaurant.

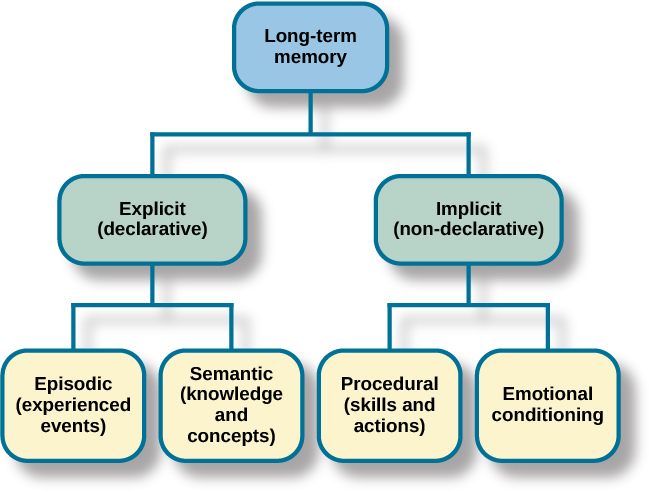

Long-term memory is divided into two types: explicit and implicit. Understanding the different types is important because a person’s age or particular types of brain trauma or disorders can leave certain types of LTM intact while having disastrous consequences for other types. Explicit memories are those we consciously try to remember and recall. For example, if you are studying for your chemistry exam, the material you are learning will be part of your explicit memory. (Note: Sometimes, but not always, the terms explicit memory and declarative memory are used interchangeably.)

Implicit memories are memories that are not part of our consciousness. They are memories formed from behaviors. Implicit memory is also called non-declarative memory.

Procedural memory is a type of implicit memory: it stores information about how to do things. It is the memory for skilled actions, such as how to brush your teeth, how to drive a car, how to swim the crawl (freestyle) stroke. If you are learning how to swim freestyle, you practice the stroke: how to move your arms, how to turn your head to alternate breathing from side to side, and how to kick your legs. You would practice this many times until you become good at it. Once you learn how to swim freestyle and your body knows how to move through the water, you will never forget how to swim freestyle, even if you do not swim for a couple of decades. Similarly, if you present an accomplished guitarist with a guitar, even if he has not played in a long time, he will still be able to play quite well.

Declarative memory has to do with the storage of facts and events we personally experienced. Explicit (declarative) memory has two parts: semantic memory and episodic memory. Semantic means having to do with language and knowledge about language. An example would be the question “what does argumentative mean?” Stored in our semantic memory is knowledge about words, concepts, and language-based knowledge and facts. For example, answers to the following questions are stored in your semantic memory:

- Who was the first President of the United States?

- What is democracy?

- What is the longest river in the world?

Episodic memory is information about events we have personally experienced. The concept of episodic memory was first proposed about \(40\) years ago (Tulving, 1972). Since then, Tulving and others have looked at scientific evidence and reformulated the theory. Currently, scientists believe that episodic memory is memory about happenings in particular places at particular times, the what, where, and when of an event (Tulving, 2002). It involves recollection of visual imagery as well as the feeling of familiarity (Hassabis & Maguire, 2007).

EVERYDAY CONNECTIONS: Can You Remember Everything You Ever Did or Said?

Episodic memories are also called autobiographical memories. Let’s quickly test your autobiographical memory. What were you wearing exactly five years ago today? What did you eat for lunch on April 10, 2009? You probably find it difficult, if not impossible, to answer these questions. Can you remember every event you have experienced over the course of your life—meals, conversations, clothing choices, weather conditions, and so on? Most likely none of us could even come close to answering these questions; however, American actress Marilu Henner, best known for the television show Taxi, can remember. She has an amazing and highly superior autobiographical memory.

Very few people can recall events in this way; right now, only \(12\) known individuals have this ability, and only a few have been studied (Parker, Cahill & McGaugh 2006). And although hyperthymesia normally appears in adolescence, two children in the United States appear to have memories from well before their tenth birthdays.

Retrieval

So you have worked hard to encode (via effortful processing) and store some important information for your upcoming final exam. How do you get that information back out of storage when you need it? The act of getting information out of memory storage and back into conscious awareness is known as retrieval. This would be similar to finding and opening a paper you had previously saved on your computer’s hard drive. Now it’s back on your desktop, and you can work with it again. Our ability to retrieve information from long-term memory is vital to our everyday functioning. You must be able to retrieve information from memory in order to do everything from knowing how to brush your hair and teeth, to driving to work, to knowing how to perform your job once you get there.

There are three ways you can retrieve information out of your long-term memory storage system: recall, recognition, and relearning. Recall is what we most often think about when we talk about memory retrieval: it means you can access information without cues. For example, you would use recall for an essay test. Recognition happens when you identify information that you have previously learned after encountering it again. It involves a process of comparison. When you take a multiple-choice test, you are relying on recognition to help you choose the correct answer. Here is another example. Let’s say you graduated from high school 10 years ago, and you have returned to your hometown for your 10-year reunion. You may not be able to recall all of your classmates, but you recognize many of them based on their yearbook photos.

The third form of retrieval is relearning, and it’s just what it sounds like. It involves learning information that you previously learned. Whitney took Spanish in high school, but after high school she did not have the opportunity to speak Spanish. Whitney is now 31, and her company has offered her an opportunity to work in their Mexico City office. In order to prepare herself, she enrolls in a Spanish course at the local community center. She’s surprised at how quickly she’s able to pick up the language after not speaking it for 13 years; this is an example of relearning.

Summary

Memory is a system or process that stores what we learn for future use.

Our memory has three basic functions: encoding, storing, and retrieving information. Encoding is the act of getting information into our memory system through automatic or effortful processing. Storage is retention of the information, and retrieval is the act of getting information out of storage and into conscious awareness through recall, recognition, and relearning. The idea that information is processed through three memory systems is called the Atkinson-Shiffrin (A-S) model of memory. First, environmental stimuli enter our sensory memory for a period of less than a second to a few seconds. Those stimuli that we notice and pay attention to then move into short-term memory (also called working memory). According to the A-S model, if we rehearse this information, then it moves into long-term memory for permanent storage. Other models like that of Baddeley and Hitch suggest there is more of a feedback loop between short-term memory and long-term memory. Long-term memory has a practically limitless storage capacity and is divided into implicit and explicit memory. Finally, retrieval is the act of getting memories out of storage and back into conscious awareness. This is done through recall, recognition, and relearning.

Glossary

- acoustic encoding

- input of sounds, words, and music

- Atkinson-Shiffrin model (A-S)

- memory model that states we process information through three systems: sensory memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory

- automatic processing

- encoding of informational details like time, space, frequency, and the meaning of words

- declarative memory

- type of long-term memory of facts and events we personally experience

- effortful processing

- encoding of information that takes effort and attention

- encoding

- input of information into the memory system

- episodic memory

- type of declarative memory that contains information about events we have personally experienced, also known as autobiographical memory

- explicit memory

- memories we consciously try to remember and recall

- implicit memory

- memories that are not part of our consciousness

- long-term memory (LTM)

- continuous storage of information

- memory

- system or process that stores what we learn for future use

- memory consolidation

- active rehearsal to move information from short-term memory into long-term memory

- procedural memory

- type of long-term memory for making skilled actions, such as how to brush your teeth, how to drive a car, and how to swim

- recall

- accessing information without cues

- recognition

- identifying previously learned information after encountering it again, usually in response to a cue

- rehearsal

- conscious repetition of information to be remembered

- relearning

- learning information that was previously learned

- retrieval

- act of getting information out of long-term memory storage and back into conscious awareness

- self-reference effect

- tendency for an individual to have better memory for information that relates to oneself in comparison to material that has less personal relevance

- semantic encoding

- input of words and their meaning

- semantic memory

- type of declarative memory about words, concepts, and language-based knowledge and facts

- sensory memory

- storage of brief sensory events, such as sights, sounds, and tastes

- short-term memory (STM)

- (also, working memory) holds about seven bits of information before it is forgotten or stored, as well as information that has been retrieved and is being used

- storage

- creation of a permanent record of information

- visual encoding

- input of images