44.2 : Biogéographie

- Page ID

- 189781

Compétences à développer

- Définir la biogéographie

- Énumérer et décrire les facteurs abiotiques qui influent sur la répartition mondiale des espèces végétales et animales

- Comparer l'impact des forces abiotiques sur les environnements aquatiques et terrestres

- Résumez l'effet des facteurs abiotiques sur la productivité primaire nette

De nombreuses forces influencent les communautés d'organismes vivants présentes dans différentes parties de la biosphère (toutes les parties de la Terre habitées par la vie). La biosphère s'étend dans l'atmosphère (plusieurs kilomètres au-dessus de la Terre) et dans les profondeurs des océans. Malgré son immensité apparente pour un être humain, la biosphère n'occupe qu'un espace infime par rapport à l'univers connu. De nombreuses forces abiotiques influencent les lieux où la vie peut exister et les types d'organismes présents dans différentes parties de la biosphère. Les facteurs abiotiques influencent la distribution des biomes : de vastes zones de terre présentant un climat, une flore et une faune similaires.

Biogéographie

La biogéographie est l'étude de la distribution géographique des êtres vivants et des facteurs abiotiques qui influent sur leur distribution. Les facteurs abiotiques tels que la température et les précipitations varient principalement en fonction de la latitude et de l'altitude. À mesure que ces facteurs abiotiques changent, la composition des communautés végétales et animales change également. Par exemple, si vous commenciez un voyage à l'équateur et que vous marchiez vers le nord, vous remarquerez des changements graduels dans les communautés végétales. Au début de votre voyage, vous verrez des forêts tropicales humides avec des arbres feuillus à feuilles persistantes, caractéristiques des communautés végétales situées près de l'équateur. En continuant à vous déplacer vers le nord, vous pourriez voir ces plantes à feuilles persistantes à feuilles larges donner naissance à des forêts sèches saisonnières avec des arbres épars. Vous commencerez également à remarquer des changements de température et d'humidité. À environ 30 degrés au nord, ces forêts céderaient la place à des déserts caractérisés par de faibles précipitations.

En vous déplaçant plus au nord, vous constaterez que les déserts sont remplacés par des prairies ou des prairies. Finalement, les prairies sont remplacées par des forêts tempérées à feuilles caduques. Ces forêts de feuillus cèdent la place aux forêts boréales de la région subarctique, au sud du cercle polaire arctique. Enfin, vous atteindrez la toundra arctique, qui se trouve aux latitudes les plus septentrionales. Cette randonnée vers le nord révèle les changements graduels du climat et des types d'organismes qui se sont adaptés aux facteurs environnementaux associés aux écosystèmes situés à différentes latitudes. Cependant, différents écosystèmes existent à la même latitude, en partie à cause de facteurs abiotiques tels que les courants-jets, le Gulf Stream et les courants océaniques. Si vous montez une montagne, les changements que vous constaterez dans la végétation seraient similaires à ceux que vous pourriez observer lorsque vous vous déplacez vers des latitudes plus élevées.

Les écologistes qui étudient la biogéographie examinent les modèles de distribution des espèces. Aucune espèce n'existe partout ; par exemple, le piège à mouches Venus est endémique à une petite région de Caroline du Nord et du Sud. Une espèce endémique est une espèce que l'on trouve naturellement uniquement dans une zone géographique spécifique dont la taille est généralement limitée. D'autres espèces sont des espèces généralistes : des espèces qui vivent dans une grande variété de zones géographiques ; le raton laveur, par exemple, est originaire de la majeure partie de l'Amérique du Nord et de l'Amérique centrale.

Les modèles de distribution des espèces sont basés sur des facteurs biotiques et abiotiques et sur leurs influences pendant les très longues périodes nécessaires à l'évolution des espèces ; par conséquent, les premières études de biogéographie étaient étroitement liées à l'émergence de la pensée évolutionniste au XVIIIe siècle. Certains des assemblages de plantes et d'animaux les plus distinctifs se trouvent dans des régions séparées physiquement depuis des millions d'années par des barrières géographiques. Les biologistes estiment que l'Australie, par exemple, compte entre 600 000 et 700 000 espèces de plantes et d'animaux. Environ 3/4 des espèces de plantes et de mammifères vivantes sont des espèces endémiques présentes uniquement en Australie (Figure\(\PageIndex{1}\)).

Parfois, les écologistes découvrent des modèles uniques de distribution des espèces en déterminant où les espèces ne se trouvent pas. Hawaï, par exemple, ne possède aucune espèce indigène de reptiles ou d'amphibiens et ne compte qu'un seul mammifère terrestre indigène, la chauve-souris grise. Autre exemple, la majeure partie de la Nouvelle-Guinée est dépourvue de mammifères placentaires.

Lien vers l'apprentissage

Regardez cette vidéo pour observer un ornithorynque nageant dans son habitat naturel en Nouvelle-Galles du Sud, en Australie.

Les plantes peuvent être endémiques ou généralistes : les plantes endémiques ne se trouvent que dans des régions spécifiques de la Terre, tandis que les généralistes se trouvent dans de nombreuses régions. Les masses terrestres isolées, comme l'Australie, Hawaï et Madagascar, abritent souvent un grand nombre d'espèces végétales endémiques. Certaines de ces plantes sont menacées en raison de l'activité humaine. Le gardénia forestier (Gardenia brighamii), par exemple, est endémique à Hawaï ; on estime qu'il n'existe que 15 à 20 arbres (Figure\(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Energy Sources

Energy from the sun is captured by green plants, algae, cyanobacteria, and photosynthetic protists. These organisms convert solar energy into the chemical energy needed by all living things. Light availability can be an important force directly affecting the evolution of adaptations in photosynthesizers. For instance, plants in the understory of a temperate forest are shaded when the trees above them in the canopy completely leaf out in the late spring. Not surprisingly, understory plants have adaptations to successfully capture available light. One such adaptation is the rapid growth of spring ephemeral plants such as the spring beauty (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). These spring flowers achieve much of their growth and finish their life cycle (reproduce) early in the season before the trees in the canopy develop leaves.

In aquatic ecosystems, the availability of light may be limited because sunlight is absorbed by water, plants, suspended particles, and resident microorganisms. Toward the bottom of a lake, pond, or ocean, there is a zone that light cannot reach. Photosynthesis cannot take place there and, as a result, a number of adaptations have evolved that enable living things to survive without light. For instance, aquatic plants have photosynthetic tissue near the surface of the water; for example, think of the broad, floating leaves of a water lily—water lilies cannot survive without light. In environments such as hydrothermal vents, some bacteria extract energy from inorganic chemicals because there is no light for photosynthesis.

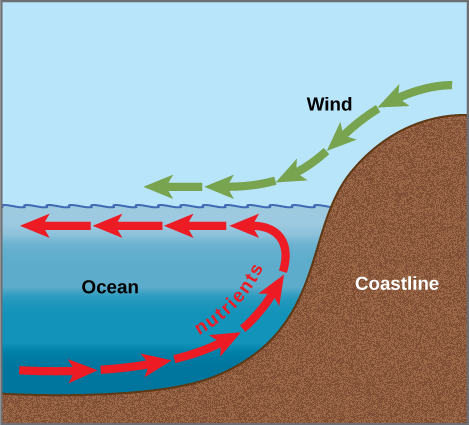

The availability of nutrients in aquatic systems is also an important aspect of energy or photosynthesis. Many organisms sink to the bottom of the ocean when they die in the open water; when this occurs, the energy found in that living organism is sequestered for some time unless ocean upwelling occurs. Ocean upwelling is the rising of deep ocean waters that occurs when prevailing winds blow along surface waters near a coastline (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). As the wind pushes ocean waters offshore, water from the bottom of the ocean moves up to replace this water. As a result, the nutrients once contained in dead organisms become available for reuse by other living organisms.

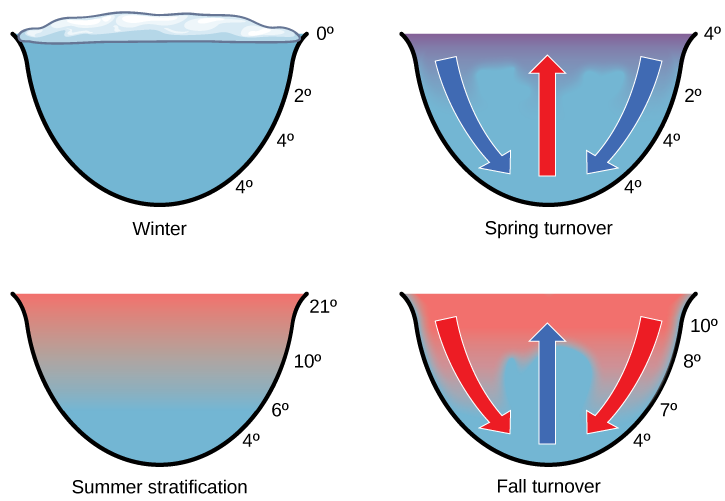

In freshwater systems, the recycling of nutrients occurs in response to air temperature changes. The nutrients at the bottom of lakes are recycled twice each year: in the spring and fall turnover. The spring and fall turnover is a seasonal process that recycles nutrients and oxygen from the bottom of a freshwater ecosystem to the top of a body of water (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). These turnovers are caused by the formation of a thermocline: a layer of water with a temperature that is significantly different from that of the surrounding layers. In wintertime, the surface of lakes found in many northern regions is frozen. However, the water under the ice is slightly warmer, and the water at the bottom of the lake is warmer yet at 4 °C to 5 °C (39.2 °F to 41 °F). Water is densest at 4 °C; therefore, the deepest water is also the densest. The deepest water is oxygen poor because the decomposition of organic material at the bottom of the lake uses up available oxygen that cannot be replaced by means of oxygen diffusion into the water due to the surface ice layer.

Art Connection

How might turnover in tropical lakes differ from turnover in lakes that exist in temperate regions?

In springtime, air temperatures increase and surface ice melts. When the temperature of the surface water begins to reach 4 °C, the water becomes heavier and sinks to the bottom. The water at the bottom of the lake is then displaced by the heavier surface water and, thus, rises to the top. As that water rises to the top, the sediments and nutrients from the lake bottom are brought along with it. During the summer months, the lake water stratifies, or forms layers, with the warmest water at the lake surface.

As air temperatures drop in the fall, the temperature of the lake water cools to 4 °C; therefore, this causes fall turnover as the heavy cold water sinks and displaces the water at the bottom. The oxygen-rich water at the surface of the lake then moves to the bottom of the lake, while the nutrients at the bottom of the lake rise to the surface (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). During the winter, the oxygen at the bottom of the lake is used by decomposers and other organisms requiring oxygen, such as fish.

Temperature

Temperature affects the physiology of living things as well as the density and state of water. Temperature exerts an important influence on living things because few living things can survive at temperatures below 0 °C (32 °F) due to metabolic constraints. It is also rare for living things to survive at temperatures exceeding 45 °C (113 °F); this is a reflection of evolutionary response to typical temperatures. Enzymes are most efficient within a narrow and specific range of temperatures; enzyme degradation can occur at higher temperatures. Therefore, organisms either must maintain an internal temperature or they must inhabit an environment that will keep the body within a temperature range that supports metabolism. Some animals have adapted to enable their bodies to survive significant temperature fluctuations, such as seen in hibernation or reptilian torpor. Similarly, some bacteria are adapted to surviving in extremely hot temperatures such as geysers. Such bacteria are examples of extremophiles: organisms that thrive in extreme environments.

Temperature can limit the distribution of living things. Animals faced with temperature fluctuations may respond with adaptations, such as migration, in order to survive. Migration, the movement from one place to another, is an adaptation found in many animals, including many that inhabit seasonally cold climates. Migration solves problems related to temperature, locating food, and finding a mate. In migration, for instance, the Arctic Tern (Sterna paradisaea) makes a 40,000 km (24,000 mi) round trip flight each year between its feeding grounds in the southern hemisphere and its breeding grounds in the Arctic Ocean. Monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) live in the eastern United States in the warmer months and migrate to Mexico and the southern United States in the wintertime. Some species of mammals also make migratory forays. Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) travel about 5,000 km (3,100 mi) each year to find food. Amphibians and reptiles are more limited in their distribution because they lack migratory ability. Not all animals that can migrate do so: migration carries risk and comes at a high energy cost.

Some animals hibernate or estivate to survive hostile temperatures. Hibernation enables animals to survive cold conditions, and estivation allows animals to survive the hostile conditions of a hot, dry climate. Animals that hibernate or estivate enter a state known as torpor: a condition in which their metabolic rate is significantly lowered. This enables the animal to wait until its environment better supports its survival. Some amphibians, such as the wood frog (Rana sylvatica), have an antifreeze-like chemical in their cells, which retains the cells’ integrity and prevents them from bursting.

Water

Water is required by all living things because it is critical for cellular processes. Since terrestrial organisms lose water to the environment by simple diffusion, they have evolved many adaptations to retain water.

- Plants have a number of interesting features on their leaves, such as leaf hairs and a waxy cuticle, that serve to decrease the rate of water loss via transpiration.

- Freshwater organisms are surrounded by water and are constantly in danger of having water rush into their cells because of osmosis. Many adaptations of organisms living in freshwater environments have evolved to ensure that solute concentrations in their bodies remain within appropriate levels. One such adaptation is the excretion of dilute urine.

- Marine organisms are surrounded by water with a higher solute concentration than the organism and, thus, are in danger of losing water to the environment because of osmosis. These organisms have morphological and physiological adaptations to retain water and release solutes into the environment. For example, Marine iguanas (Amblyrhynchus cristatus), sneeze out water vapor that is high in salt in order to maintain solute concentrations within an acceptable range while swimming in the ocean and eating marine plants.

Inorganic Nutrients and Soil

Inorganic nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, are important in the distribution and the abundance of living things. Plants obtain these inorganic nutrients from the soil when water moves into the plant through the roots. Therefore, soil structure (particle size of soil components), soil pH, and soil nutrient content play an important role in the distribution of plants. Animals obtain inorganic nutrients from the food they consume. Therefore, animal distributions are related to the distribution of what they eat. In some cases, animals will follow their food resource as it moves through the environment.

Other Aquatic Factors

Some abiotic factors, such as oxygen, are important in aquatic ecosystems as well as terrestrial environments. Terrestrial animals obtain oxygen from the air they breathe. Oxygen availability can be an issue for organisms living at very high elevations, however, where there are fewer molecules of oxygen in the air. In aquatic systems, the concentration of dissolved oxygen is related to water temperature and the speed at which the water moves. Cold water has more dissolved oxygen than warmer water. In addition, salinity, current, and tide can be important abiotic factors in aquatic ecosystems.

Other Terrestrial Factors

Wind can be an important abiotic factor because it influences the rate of evaporation and transpiration. The physical force of wind is also important because it can move soil, water, or other abiotic factors, as well as an ecosystem’s organisms.

Fire is another terrestrial factor that can be an important agent of disturbance in terrestrial ecosystems. Some organisms are adapted to fire and, thus, require the high heat associated with fire to complete a part of their life cycle. For example, the jack pine—a coniferous tree—requires heat from fire for its seed cones to open (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). Through the burning of pine needles, fire adds nitrogen to the soil and limits competition by destroying undergrowth.

Abiotic Factors Influencing Plant Growth

Temperature and moisture are important influences on plant production (primary productivity) and the amount of organic matter available as food (net primary productivity). Net primary productivity is an estimation of all of the organic matter available as food; it is calculated as the total amount of carbon fixed per year minus the amount that is oxidized during cellular respiration. In terrestrial environments, net primary productivity is estimated by measuring the aboveground biomass per unit area, which is the total mass of living plants, excluding roots. This means that a large percentage of plant biomass which exists underground is not included in this measurement. Net primary productivity is an important variable when considering differences in biomes. Very productive biomes have a high level of aboveground biomass.

Annual biomass production is directly related to the abiotic components of the environment. Environments with the greatest amount of biomass have conditions in which photosynthesis, plant growth, and the resulting net primary productivity are optimized. The climate of these areas is warm and wet. Photosynthesis can proceed at a high rate, enzymes can work most efficiently, and stomata can remain open without the risk of excessive transpiration; together, these factors lead to the maximal amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) moving into the plant, resulting in high biomass production. The aboveground biomass produces several important resources for other living things, including habitat and food. Conversely, dry and cold environments have lower photosynthetic rates and therefore less biomass. The animal communities living there will also be affected by the decrease in available food.

Summary

Biogeography is the study of the geographic distribution of living things and the abiotic factors that affect their distribution. Endemic species are species that are naturally found only in a specific geographic area. The distribution of living things is influenced by several environmental factors that are, in part, controlled by the latitude or elevation at which an organism is found. Ocean upwelling and spring and fall turnovers are important processes regulating the distribution of nutrients and other abiotic factors important in aquatic ecosystems. Energy sources, temperature, water, inorganic nutrients, and soil are factors limiting the distribution of living things in terrestrial systems. Net primary productivity is a measure of the amount of biomass produced by a biome.

Art Connections

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): How might turnover in tropical lakes differ from turnover in lakes that exist in temperate regions?

- Answer

-

Tropical lakes don’t freeze, so they don’t undergo spring turnover in the same way temperate lakes do. However, stratification does occur, as well as seasonal turnover.

Glossary

- aboveground biomass

- total mass of aboveground living plants per area

- biogeography

- study of the geographic distribution of living things and the abiotic factors that affect their distribution

- biome

- ecological community of plants, animals, and other organisms that is adapted to a characteristic set of environmental conditions

- endemic

- species found only in a specific geographic area that is usually restricted in size

- fall and spring turnover

- seasonal process that recycles nutrients and oxygen from the bottom of a freshwater ecosystem to the top

- net primary productivity

- measurement of the energy accumulation within an ecosystem, calculated as the total amount of carbon fixed per year minus the amount that is oxidized during cellular respiration

- ocean upwelling

- rising of deep ocean waters that occurs when prevailing winds blow along surface waters near a coastline

- thermocline

- layer of water with a temperature that is significantly different from that of the surrounding layers