33.1: شكل الحيوان ووظيفته

- Page ID

- 196290

مهارات التطوير

- وصف الأنواع المختلفة من خطط الجسم التي تحدث في الحيوانات

- وصف حدود حجم الحيوان وشكله

- اربط الطاقة الحيوية بحجم الجسم ومستويات النشاط والبيئة

تختلف الحيوانات في الشكل والوظيفة. من الإسفنج إلى الدودة إلى الماعز، يتمتع الكائن الحي بخطة جسم مميزة تحد من حجمه وشكله. تم تصميم أجسام الحيوانات أيضًا للتفاعل مع بيئاتها، سواء في أعماق البحار أو مظلة الغابات المطيرة أو الصحراء. لذلك، يمكن تعلم كمية كبيرة من المعلومات حول بنية جسم الكائن الحي (علم التشريح) ووظيفة خلاياه وأنسجته وأعضائه (علم وظائف الأعضاء) من خلال دراسة بيئة ذلك الكائن الحي.

خطط الجسم

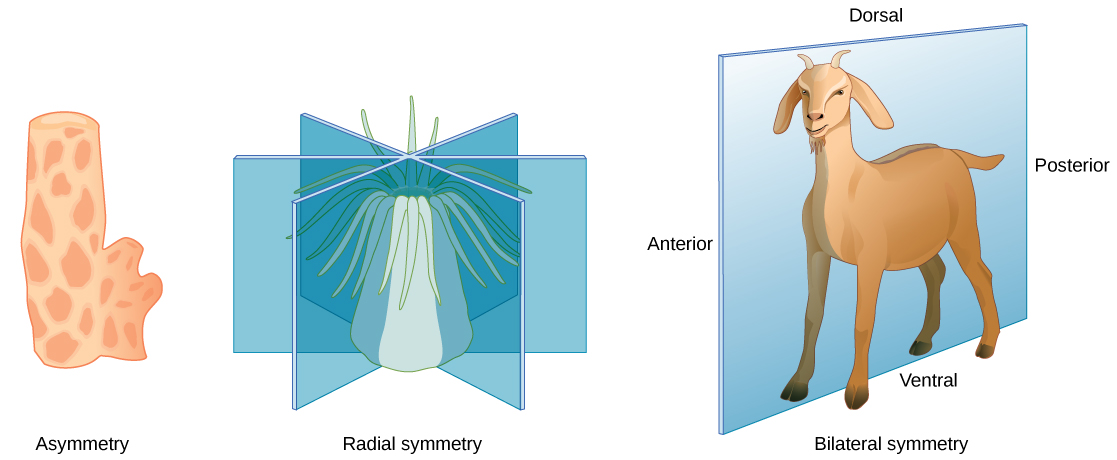

تتبع خطط جسم الحيوان أنماطًا محددة تتعلق بالتماثل. وهي غير متماثلة أو شعاعية أو ثنائية في الشكل كما هو موضح في الشكل\(\PageIndex{1}\). الحيوانات غير المتماثلة هي حيوانات ليس لها نمط أو تماثل؛ ومثال الحيوان غير المتماثل هو الإسفنج. التماثل الشعاعي، كما هو موضح في الشكل\(\PageIndex{1}\)، يصف عندما يكون للحيوان اتجاه صعودًا وهبوطًا: أي مستوى يقطع على طول محوره الطولي عبر الكائن الحي ينتج نصفين متساويين، ولكن ليس جانبًا يمينًا أو يسارًا محددًا. توجد هذه النباتات في الغالب في الحيوانات المائية، وخاصة الكائنات الحية التي تلتصق بقاعدة، مثل الصخور أو القوارب، وتستخرج طعامها من المياه المحيطة أثناء تدفقها حول الكائن الحي. يتم توضيح التماثل الثنائي في نفس الشكل بواسطة عنزة. يحتوي الماعز أيضًا على مكون علوي وسفلي، لكن الطائرة المقطوعة من الأمام إلى الخلف تفصل الحيوان إلى الجانبين الأيمن والأيسر المحددين. المصطلحات الإضافية المستخدمة عند وصف المواضع في الجسم هي الأمامية (الأمامية) والخلفية (الخلفية) والظهرية (باتجاه الظهر) والبطنية (باتجاه المعدة). يوجد التناظر الثنائي في كل من الحيوانات البرية والمائية؛ فهو يتيح مستوى عاليًا من الحركة.

حدود حجم الحيوان وشكله

تميل الحيوانات ذات التماثل الثنائي التي تعيش في الماء إلى أن يكون لها شكل مغزلي: هذا جسم أنبوبي الشكل مدبب من كلا الطرفين. يقلل هذا الشكل من الشد على الجسم أثناء تحركه عبر الماء ويسمح للحيوان بالسباحة بسرعات عالية. يسرد الجدول أدناه السرعة القصوى للحيوانات المختلفة. يمكن لأنواع معينة من أسماك القرش السباحة بسرعة خمسين كيلومترًا في الساعة وبعض الدلافين بسرعة 32 إلى 40 كيلومترًا في الساعة. غالبًا ما تسافر الحيوانات البرية بشكل أسرع، على الرغم من أن السلحفاة والحلزون أبطأ بكثير من الفهود. هناك اختلاف آخر في تكيفات الكائنات المائية والكائنات التي تعيش على الأرض وهو أن الكائنات المائية مقيدة في الشكل بفعل قوى السحب في الماء لأن الماء له لزوجة أعلى من الهواء. من ناحية أخرى، فإن الكائنات الحية التي تعيش على الأرض مقيدة بشكل أساسي بالجاذبية، والسحب غير مهم نسبيًا. على سبيل المثال، معظم التكيفات في الطيور مخصصة للجاذبية وليس للسحب.

| حيوان | السرعة (كم/ساعة) | السرعة (ميل في الساعة) |

|---|---|---|

| الفهد | 113 | 70 |

| كوارتر هورس | 77 | 48 |

| ثعلب | 68 | 42 |

| سمكة قرش ماكو قصيرة الزعانف | 50 | 31 |

| قطة منزلية منزلية | 48 | 30 |

| الإنسان | 45 | 28 |

| دولفين | 32-40 | 20-25 |

| الماوس | 13 | 8 |

| حلزون | 0.05 | 0.03 |

تحتوي معظم الحيوانات على هيكل خارجي، بما في ذلك الحشرات والعناكب والعقارب وسرطان البحر على شكل حدوة حصان والحيوانات والقشريات. يقدر العلماء أنه من بين الحشرات وحدها، هناك أكثر من 30 مليون نوع على كوكبنا. الهيكل الخارجي عبارة عن غطاء صلب أو غلاف يوفر فوائد للحيوان، مثل الحماية من التلف الناتج عن الحيوانات المفترسة ومن فقدان الماء (للحيوانات البرية)؛ كما أنه يوفر روابط العضلات.

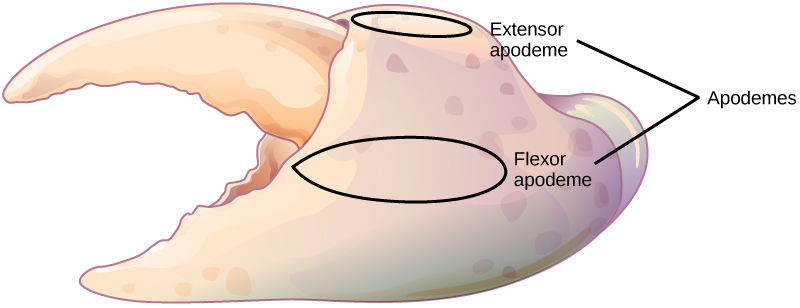

كغطاء خارجي صلب ومقاوم للمفصليات، يمكن بناء الهيكل الخارجي من بوليمر صلب مثل الكيتين وغالبًا ما يتم تمعدنه بيولوجيًا بمواد مثل كربونات الكالسيوم. يتم دمج هذا في بشرة الحيوان. تعمل أورام الهيكل الخارجي، التي تسمى الأوديمات، كمواقع ربط للعضلات، على غرار الأوتار في الحيوانات الأكثر تقدمًا (الشكل\(\PageIndex{2}\)). من أجل النمو، يجب على الحيوان أولاً تركيب هيكل خارجي جديد تحت الهيكل القديم ثم التخلص من الغطاء الأصلي أو صهره. هذا يحد من قدرة الحيوان على النمو باستمرار، وقد يحد من قدرة الفرد على النضج إذا لم يحدث طرح الريش في الوقت المناسب. يجب زيادة سمك الهيكل الخارجي بشكل كبير لاستيعاب أي زيادة في الوزن. تشير التقديرات إلى أن مضاعفة حجم الجسم تزيد من وزن الجسم بعامل ثمانية. إن زيادة سمك الكيتين الضروري لدعم هذا الوزن تحد من معظم الحيوانات ذات الهيكل الخارجي إلى حجم صغير نسبيًا. تنطبق نفس المبادئ على الهياكل الداخلية، لكنها أكثر كفاءة لأن العضلات متصلة من الخارج، مما يسهل التعويض عن زيادة الكتلة.

يتم تحديد حجم الحيوان الذي يحتوي على هيكل داخلي من خلال كمية النظام الهيكلي التي يحتاجها لدعم الأنسجة الأخرى وكمية العضلات التي يحتاجها للحركة. مع زيادة حجم الجسم، تزداد كتلة العظام والعضلات. السرعة التي يمكن أن يحققها الحيوان هي التوازن بين حجمه الكلي والعظام والعضلات التي توفر الدعم والحركة.

الحد من آثار الانتشار على الحجم والتطوير

يحدث تبادل العناصر الغذائية والنفايات بين الخلية وبيئتها المائية من خلال عملية الانتشار. يتم غسل جميع الخلايا الحية في السائل، سواء كانت في كائن أحادي الخلية أو كائن متعدد الخلايا. يكون الانتشار فعالًا على مسافة محددة ويحد من الحجم الذي يمكن أن تحققه الخلية الفردية. إذا كانت الخلية عبارة عن كائن حي دقيق أحادي الخلية، مثل الأميبا، فيمكنها تلبية جميع احتياجاتها من المغذيات والنفايات من خلال الانتشار. إذا كانت الخلية كبيرة جدًا، فإن الانتشار يكون غير فعال ولا يتلقى مركز الخلية العناصر الغذائية الكافية ولا يمكنه تبديد نفاياتها بشكل فعال.

أحد المفاهيم المهمة في فهم مدى كفاءة الانتشار كوسيلة للنقل هو نسبة السطح إلى الحجم. تذكر أن أي جسم ثلاثي الأبعاد له مساحة سطح وحجم؛ نسبة هاتين الكميتين هي نسبة سطح إلى حجم. ضع في اعتبارك خلية على شكل كرة مثالية: تبلغ مساحتها السطحية 4r 2، وحجمها (4/3) r 3. نسبة سطح إلى حجم الكرة هي 3/r؛ كلما كبرت الخلية، تنخفض نسبة سطحها إلى حجمها، مما يجعل الانتشار أقل كفاءة. كلما زاد حجم الكرة أو الحيوان، قلت مساحة سطح الانتشار التي تمتلكها.

الحل لإنتاج كائنات حية أكبر هو أن تصبح متعددة الخلايا. يحدث التخصص في الكائنات الحية المعقدة، مما يسمح للخلايا بأن تصبح أكثر كفاءة في القيام بمهام أقل. على سبيل المثال، تجلب أنظمة الدورة الدموية العناصر الغذائية وتزيل النفايات، بينما توفر أنظمة الجهاز التنفسي الأكسجين للخلايا وتزيل ثاني أكسيد الكربون منها. طورت أنظمة الأعضاء الأخرى مزيدًا من التخصص للخلايا والأنسجة وتتحكم بكفاءة في وظائف الجسم. علاوة على ذلك، تنطبق نسبة السطح إلى الحجم على مجالات أخرى من التطور الحيواني، مثل العلاقة بين كتلة العضلات ومساحة سطح المقطع العرضي في الهياكل العظمية الداعمة، وفي العلاقة بين كتلة العضلات وتوليد تبديد الحرارة.

الطاقة الحيوية الحيوانية

يجب أن تحصل جميع الحيوانات على طاقتها من الطعام الذي تتناوله أو تمتصه. يتم تحويل هذه العناصر الغذائية إلى ثلاثي فوسفات الأدينوزين (ATP) للتخزين قصير المدى والاستخدام من قبل جميع الخلايا. تقوم بعض الحيوانات بتخزين الطاقة لفترات أطول قليلاً مثل الجليكوجين، بينما يخزن البعض الآخر الطاقة لفترات أطول في شكل الدهون الثلاثية الموجودة في الأنسجة الدهنية المتخصصة. لا يوجد نظام للطاقة فعال بنسبة مائة بالمائة، وينتج التمثيل الغذائي للحيوان طاقة مهدرة في شكل حرارة. إذا كان الحيوان قادرًا على الحفاظ على تلك الحرارة والحفاظ على درجة حرارة ثابتة نسبيًا للجسم، فسيتم تصنيفه على أنه حيوان ذو دم دافئ ويسمى ماص الحرارة. يأتي العزل المستخدم للحفاظ على حرارة الجسم على شكل فراء أو دهون أو ريش. يزيد غياب العزل في الحيوانات ذات الحرارة الخارجية من اعتمادها على البيئة من أجل حرارة الجسم.

تُسمى كمية الطاقة التي ينفقها الحيوان خلال فترة زمنية محددة بمعدل الأيض. يتم قياس المعدل بشكل مختلف بالجول أو السعرات الحرارية أو السعرات الحرارية (1000 سعر حراري). تحتوي الكربوهيدرات والبروتينات على حوالي 4.5 إلى 5 كيلو كالوري/جرام، وتحتوي الدهون على حوالي 9 كيلو كالوري/جرام، ويقدر معدل الأيض على أنه معدل الأيض القاعدي (BMR) في الحيوانات الماصة للحرارة أثناء الراحة وكمعدل الأيض القياسي (SMR) في درجات الحرارة الخارجية. يبلغ معدل الأيض الأساسي للذكور من 1600 إلى 1800 كيلو كالوري/اليوم، ولدى الإناث معدل الأيض الأساسي من 1300 إلى 1500 سعرة حرارية في اليوم. حتى مع العزل، تتطلب الحيوانات الحرارية الداخلية كميات كبيرة من الطاقة للحفاظ على درجة حرارة ثابتة للجسم. تبلغ نسبة SMR في الحرارة الخارجية مثل التمساح 60 سعرة حرارية في اليوم.

متطلبات الطاقة المتعلقة بحجم الجسم

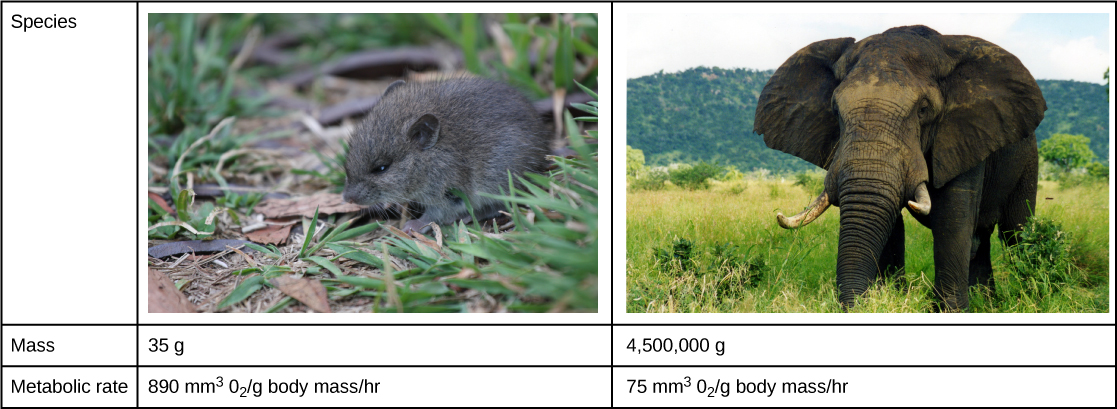

تحتوي الحيوانات الماصة للحرارة الأصغر على مساحة سطح أكبر لكتلتها مقارنة بالحيوانات الأكبر حجمًا (الشكل)\(\PageIndex{3}\)). Therefore, smaller animals lose heat at a faster rate than larger animals and require more energy to maintain a constant internal temperature. This results in a smaller endothermic animal having a higher BMR, per body weight, than a larger endothermic animal.

Energy Requirements Related to Levels of Activity

The more active an animal is, the more energy is needed to maintain that activity, and the higher its BMR or SMR. The average daily rate of energy consumption is about two to four times an animal’s BMR or SMR. Humans are more sedentary than most animals and have an average daily rate of only 1.5 times the BMR. The diet of an endothermic animal is determined by its BMR. For example: the type of grasses, leaves, or shrubs that an herbivore eats affects the number of calories that it takes in. The relative caloric content of herbivore foods, in descending order, is tall grasses > legumes > short grasses > forbs (any broad-leaved plant, not a grass) > subshrubs > annuals/biennials.

Energy Requirements Related to Environment

Animals adapt to extremes of temperature or food availability through torpor. Torpor is a process that leads to a decrease in activity and metabolism and allows animals to survive adverse conditions. Torpor can be used by animals for long periods, such as entering a state of hibernation during the winter months, in which case it enables them to maintain a reduced body temperature. During hibernation, ground squirrels can achieve an abdominal temperature of 0° C (32° F), while a bear’s internal temperature is maintained higher at about 37° C (99° F).

If torpor occurs during the summer months with high temperatures and little water, it is called estivation. Some desert animals use this to survive the harshest months of the year. Torpor can occur on a daily basis; this is seen in bats and hummingbirds. While endothermy is limited in smaller animals by surface to volume ratio, some organisms can be smaller and still be endotherms because they employ daily torpor during the part of the day that is coldest. This allows them to conserve energy during the colder parts of the day, when they consume more energy to maintain their body temperature.

Animal Body Planes and Cavities

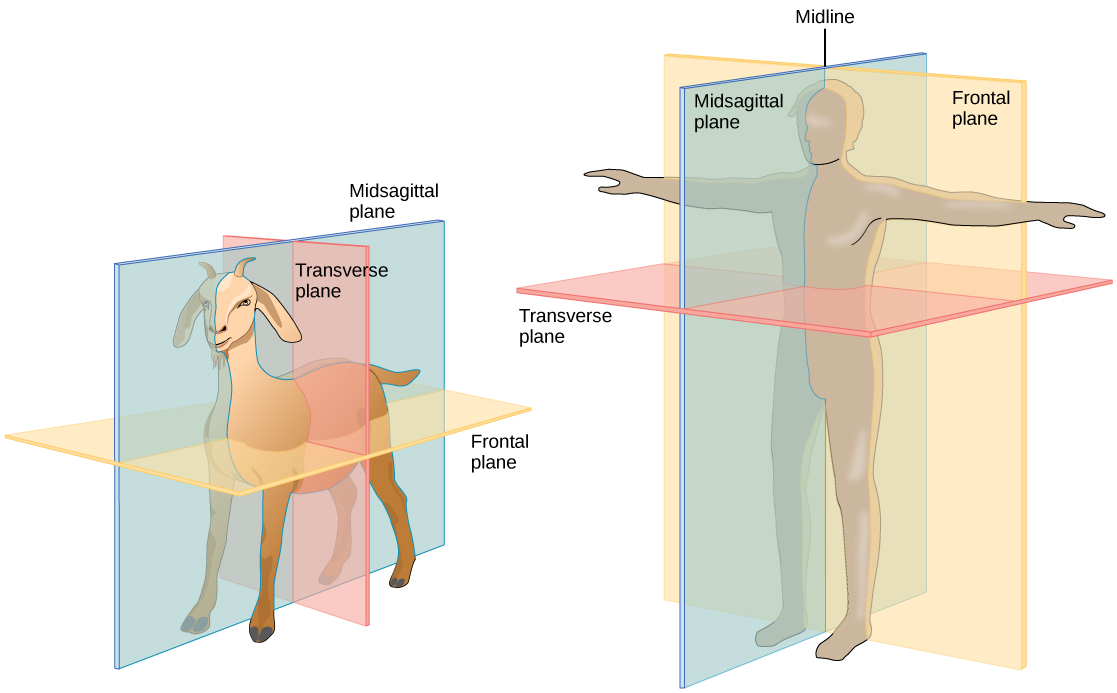

A standing vertebrate animal can be divided by several planes. A sagittal plane divides the body into right and left portions. A midsagittal plane divides the body exactly in the middle, making two equal right and left halves. A frontal plane (also called a coronal plane) separates the front from the back. A transverse plane (or, horizontal plane) divides the animal into upper and lower portions. This is sometimes called a cross section, and, if the transverse cut is at an angle, it is called an oblique plane. Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) illustrates these planes on a goat (a four-legged animal) and a human being.

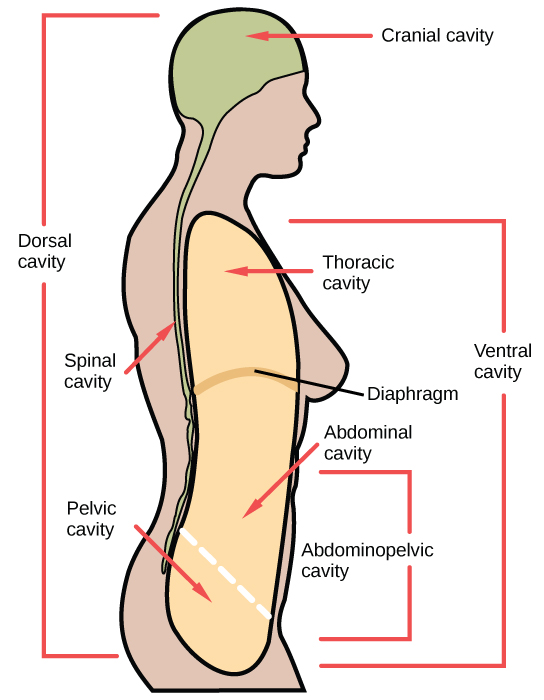

Vertebrate animals have a number of defined body cavities, as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\). Two of these are major cavities that contain smaller cavities within them. The dorsal cavity contains the cranial and the vertebral (or spinal) cavities. The ventral cavity contains the thoracic cavity, which in turn contains the pleural cavity around the lungs and the pericardial cavity, which surrounds the heart. The ventral cavity also contains the abdominopelvic cavity, which can be separated into the abdominal and the pelvic cavities.

Career Connections: Physical Anthropologist

Physical anthropologists study the adaption, variability, and evolution of human beings, plus their living and fossil relatives. They can work in a variety of settings, although most will have an academic appointment at a university, usually in an anthropology department or a biology, genetics, or zoology department.

Non-academic positions are available in the automotive and aerospace industries where the focus is on human size, shape, and anatomy. Research by these professionals might range from studies of how the human body reacts to car crashes to exploring how to make seats more comfortable. Other non-academic positions can be obtained in museums of natural history, anthropology, archaeology, or science and technology. These positions involve educating students from grade school through graduate school. Physical anthropologists serve as education coordinators, collection managers, writers for museum publications, and as administrators. Zoos employ these professionals, especially if they have an expertise in primate biology; they work in collection management and captive breeding programs for endangered species. Forensic science utilizes physical anthropology expertise in identifying human and animal remains, assisting in determining the cause of death, and for expert testimony in trials.

Summary

Animal bodies come in a variety of sizes and shapes. Limits on animal size and shape include impacts to their movement. Diffusion affects their size and development. Bioenergetics describes how animals use and obtain energy in relation to their body size, activity level, and environment.

Glossary

- apodeme

- ingrowth of an animal’s exoskeleton that functions as an attachment site for muscles

- asymmetrical

- describes animals with no axis of symmetry in their body pattern

- basal metabolic rate (BMR)

- metabolic rate at rest in endothermic animals

- dorsal cavity

- body cavity on the posterior or back portion of an animal; includes the cranial and vertebral cavities

- ectotherm

- animal incapable of maintaining a relatively constant internal body temperature

- endotherm

- animal capable of maintaining a relatively constant internal body temperature

- estivation

- torpor in response to extremely high temperatures and low water availability

- frontal (coronal) plane

- plane cutting through an animal separating the individual into front and back portions

- fusiform

- animal body shape that is tubular and tapered at both ends

- hibernation

- torpor over a long period of time, such as a winter

- midsagittal plane

- plane cutting through an animal separating the individual into even right and left sides

- sagittal plane

- plane cutting through an animal separating the individual into right and left sides

- standard metabolic rate (SMR)

- metabolic rate at rest in ectothermic animals

- torpor

- decrease in activity and metabolism that allows an animal to survive adverse conditions

- transverse (horizontal) plane

- plane cutting through an animal separating the individual into upper and lower portions

- ventral cavity

- body cavity on the anterior or front portion of an animal that includes the thoracic cavities and the abdominopelvic cavities